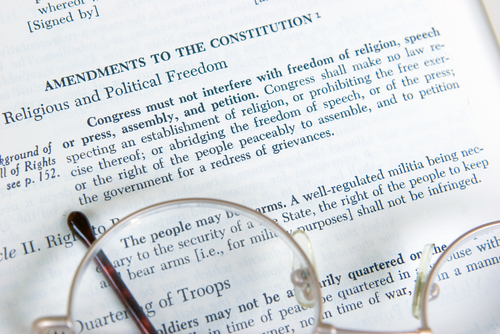

Continuing with our ongoing legal series, the time has come to discuss specific parts of the US Constitution. We’ll start at the beginning with something that’s been on everyone’s minds lately: the first amendment. Don’t automatically feel bad if you don’t know what the first amendment truly means. Half of our government seems to have forgotten it as well, and we’re here to educate. Like most of the Bill of Rights, the first amendment isn’t long, but a great deal of power and law has come from some simple words. Let’s review:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

When the constitution says “congress,” it means all branches of government, state and federal. This wasn’t always clear, but it’s the standard now. As you can see, there’s several different clauses, each addressing massively important basics of American life. We’ll look at them individually.

Freedom of Religion

There are two important bits here: the establishment clause and the free exercise clause. The establishment clause seems simple: the government does not get to establish a state religion or favor one religion over another. Of course, America never does anything the easy way. Religious actions and symbols get used by the government all the time – prayers before legislative sessions and putting “In God We Trust” on money for instance. The erection of religious monuments on government land had been highly controversial and much litigated. The Supreme Court addressed that later, but the law remains murky. Still, things like favoring Christians over Muslims in immigration probably violate that provision.

The free exercise clause also seems simple. It holds that congress can’t make laws that limit people’s religious practices. Great! But let’s follow that further; in the event a religiously neutral law impinges on a religious practice, those people should be exempt, right? For example, during prohibition, makers of wine used for religious purposes were not shut down (in fact, their industry experienced mysterious surge). Exceptions like that seem all well and good until we get to things like religions that require, say, animal sacrifice. In a famous case, the Supreme court held that neutral regulations can burden religion, but not ones that specifically target religion. So a city ordinance specifically barring animal sacrifice for religious purposes was struck down. Presently, there is an ongoing controversy as to whether discrimination based on sexuality or gender, contrary to civil rights law, is an extension of people’s first amendment free exercise rights. Denying basic services or protection to other people doesn’t sound like something Jesus would do, but it’s the argument being made. And doesn’t the constitution say we shouldn’t give religions special treatment anyway?

Some scholars feel that the free exercise clause and establishment clause are in direct conflict, because exemptions to obedience of the law based on religion inherently favors religion, in direct defiance of the establishment clause, and they have a point. The malleability and variation of religion can create serious conflicts between religious practice and the rule of law and the line is not easily drawn. What about religions that favor bigamy? Or condone abuse? The state clearly cannot outlaw a religion, but the reach of the free exercise clause is vague. What’s the consequence of that? Well, it means that the time is ripe for a big case. We have already had the Hobby Lobby case, which allowed exemptions for privately owned, non-public (as in not having stock holders) businesses to get exemption from providing certain insurance coverage under the Affordable Care Act, or Obamacare. We may not want an expansion of that doctrine, so a showdown isn’t something to hope for necessarily.

Free Speech

The free speech provisions of the first amendment are complex and subject to a lot of misconceptions. The big one first: the constitution limits government control of speech. If the government is not involved, it’s not a free speech issue. Someone getting suspended on Twitter or being told to not be a jerk is not an infringement on their free speech rights. Now, back to the government. The freedom of speech, of the press, and free assembly are all subtly different but the main thrust is the government can’t limit those things. They can’t make certain types of speech illegal. This isn’t always great: America’s laws are actually very liberal in comparison to some other countries, where things like hate speech or denying the holocaust are explicitly banned. But on the other hand, it’s legal for me to call the leader of our country a desiccated butternut squash with the hands of a toddler and the intelligence of a particularly spiteful block of moldy cheese, so the trade off could be worth it.

The government cannot create what’s called a “prior restraint,” that is, banning specific types of speech. However, they can limit or punish certain types of speech if there is a compelling government interest in doing so. You may be familiar with the idiom “you can’t yell fire in a theater,” and that’s the general idea. If you say something, in life or in the press, that causes or incites harm, the government can come in and tell you no. Things like defamation come in here, or inciting illegal action. Additionally, the freedom of assembly can be limited for things like public safety and order (that’s why it’s not unconstitutional to require a permit for a large protest or parade). Here’s where we meet something called the Brandenburg Doctrine, based on Brandenburg v. Ohio, a 1969 Supreme Court case which involved the KKK. The state can limit or punish speech that incites imminent “lawless action” and that is likely to incite such action. This is good, because it’s a strict test, but we have to be careful in case the state tries to over expand their definition of lawless action. However, political speech is especially protected from state limitation, which is why burning flag and naked bike rides are protected speech. The take away: laws or executive orders that in any way tried to limit reporting or punish peaceful protesters would be completely unconstitutional.

What about all this stuff about keeping the press out of briefings and other interactions? Well, that’s just the actions of the administration, not laws. It’s a stupid, unproductive move, but it does not rise to the level or a prior restraint. No outlets have been told what to write, just denied access because someone might know that actual legal action against the press would be impossible and unconstitutional. The attempts by the administration to limit press access is a troubling and foolish action to be sure, but not at this point unconstitutional. It’s also counter-productive, and betrays that they know honest reporting will show them in a bad light. But that’s why the free press exists.

When we look at the first amendment and what it protects, especially now, it’s important to remember its historical context in comparison. The first amendment as drafted in response to tyranny and a government that sought to limit the press and assembly and speech when rebellion was rising. The free exercise and establishment clauses were both in response to centuries of religious strife. The founding fathers, unlike some people in our government now, actually tried to learn from the past and protect their new nation from the dangers of religious hatred or oppression. It’s a good thing they did, because the first amendment is, and will remain, the first line of defense against such tyrants.

(image via Shutterstock/James E. Knopf)

Jessica Mason is a writer and lawyer living in Portland, Oregon passionate about corgis, fandom, and awesome girls. Follow her on Twitter at @FangirlingJess.

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google+.

Published: Mar 2, 2017 01:42 pm