Looking At Female Characters in Anime and Manga Through a Western Feminist Lens

Well, here it goes.

[Editor’s Note: You may have noticed Alvina Lai’s byline on TMS the last few months. She was our latest intern and we’re saying so long to her today with her final project with us here. We hope you’ll join us in wishing her well!]

[Editor’s Note: You may have noticed Alvina Lai’s byline on TMS the last few months. She was our latest intern and we’re saying so long to her today with her final project with us here. We hope you’ll join us in wishing her well!]

The portrayal of female characters in anime and manga is a complex discussion, not only because of the various tropes that exist but also because of the cultural perspectives through which they must be filtered and digested. The girls in Sailor Moon mean something different than the protagonist of Princess Mononoke, and they are also different from the female characters created by the all-women’s group CLAMP. While the subject of female characters in anime and manga is not as frequently written about as other popular entertainment such as LOTR or Game of Thrones here at The Mary Sue or even in North America overall, it nonetheless has become a topic of discussion not only by the Japanese consumers but also by those who, like myself, have only a limited but enthusiastic experience of watching anime and reading manga and would want further discussion of the subject.

In order to explore the magnitude of anime with essential female characters, a general understanding of genres involving female characters comes in handy. For example, josei is a genre generally aimed at young adult and adult women while shoujo is more geared towards younger girls. Both can encompass romantic plots, but romance can exist as its own genre. Anime and manga tend to fit into more than one genre and are not only organized by subject but age group. However, because of this, it is understandable that certain character traits would be more prominent in one genre than another.

Shoujo often addresses a girl’s first love, and the innocent excitement and sometimes painful drama that comes with it. It also deals with friendship and personal development. A recent popular shoujo is Wolf Girl and Black Prince. An older popular one is Fruit Baskets. A personal favorite of mine, Gekkan Shoujo Nozaki-kun, parodies the genre. This is a very different feeling than the popular ongoing manga Princess Jellyfish (which I recommend) and some other ones we have discussed. The josei genre is where the understanding of adulthood, and what it means to be a woman, seeps into daily life and with that a sense of maturity and—maybe for some—disillusionment. Of course, the lines often blur in terms of which genre a manga can go into, but nonetheless such genres are a reason why female character tropes, some more positive than others, become prominent in the work.

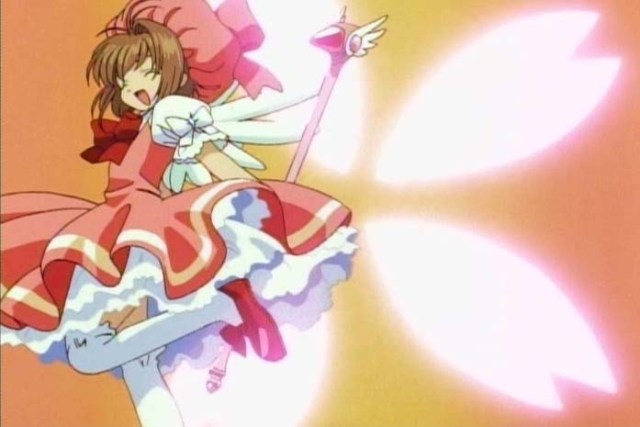

So what does this mean for female characters? Well, as certain characteristics are visible in dramas or sitcoms, the protagonists of josei and shoujo, or any genre in general, have relatable but sometimes simple personalities: innocent characters, tsundere characters, the kind and helpful characters, the cute and oblivious characters, and so on. Sometimes, this can lead to a development of strong, admirable female characters with interesting development, but it can also lead to oversimplification, sexualization, and objectification as well. A case study would be two stories created by CLAMP, an all-female mangaka group who have been in the industry for many, many years. They’re known for Cardcaptor Sakura, a shoujo that I grew up with, and a more controversial project, Chobits.

Cardcaptor Sakura is about a girl, Sakura, who opens a book that contain magical cards, Clow Cards, that scatter across her hometown. Her job is to get these cards back. This magical adventure is a comedy and a romance, but overall, you get a sense of a willful, brave, goodhearted girl who you watch grow as a person. Chobits is about a guy who finds a persocon, a human-like robot, in the trash. But in order to turn her on, literally, he has to push the switch located at her crotch. Her name is Chii and because she has no memory, she’s completely dependent on her finder. She’s a sweet and lovable character but without depth, and that dangerously reinforces the stereotype that women are submissive and cute, a sexist and problematic view. Chobits happens to be categorized as ecchi, a more sexual genre, and seinen, a genre geared at older boys and men, so it is not aimed at girls as a model for what being a girl is, like CCS, but it is problematic despite that.

So how does an all-female mangaka group make a strong female character like Sakura while at the same time have characters that are essentially seen as sexual objects? Of course, there’s a clear intent in regards to the audience. One story inspires young girls while the other fulfills certain fantasies. We discussed female anime characters in hentai, a genre that’s all about sex, and the treatment and portayal of women was clearly an issue.

While Western social values of women are shifting towards equality, we have not yet completely resolved problems such as undesired sexualization or objectification. However we are recognizing them as issues and are working towards resolving them. Therefore, we are seeing the objectification and sexualization as an issue through our perspective. In order to truly see if this is an issue to Japanese society, and in order to avoid applying our ideas to another society, the subject of the portrayal of girls and women in anime and manga needs to be seen from the perspective of those who it affects most. How do Japanese women and anime and manga consumers see and interpret this sexualization?

Earlier this year, a Japanese Twitter user @ykhre tweeted a controversial essay in making a case about the problematic sexism in a popular manga and anime, One Piece. While she was not looking to disrespect the series, she nonetheless highlighted issues of underlying themes.

I just think that the underlying themes of ‘women are weak,’ ‘oversexualization,’ ‘if she’s ugly it’s okay to beat her up,’ and ‘okama are creepy,’ are covered up in a nice disguise of romanticized pirates going on an adventure.

She criticized the background of the male characters, the weakening of male characters when they were drawn as female characters, and how the women characters are portrayed to be uninteresting and weak. So Japanese netizens responded.

There was a wide spectrum of comments, from agreement to indifference to attacking @ykhre, which can be read on Rocket News 24. It should be noted that the complexity of the situation stems from the well crafted storyline, back stories, character relationships, and universe in One Piece, which means there are multiple layers in how women are portrayed, some being much more developed and well-rounded than others. Despite that, @ykhre has a legitimate concern. The portrayal of women in anime and manga is indeed a topic of conversation, but how it relates to or reflects the role of women and the extent of sexism in Japanese society is a bigger and even more complex discussion.

Another anime which has been a hot topic of discussion in the past anime year in regards to sexism is Kill La Kill. Ryuko, the protagonist, is on a search for her father and has the help of a talking school uniform that transforms when she wears it as she fights. The school uniform is the topic of debate. Does the uniform represent her being sexualized and submitting to her situation, or does it show empowerment through her willingness to wear it and get over the embarrassment of doing so? When does intent become justification and does the male-heavy staff affect it in a way that Chobit‘s female staff doesn’t? It depends on who you’re asking.

Of course, there are some more definite positive portrayals of girls and women in anime and manga, such as those found in Card Captor Sakura or Sailor Moon. Sailor Moon has found fans across the world and has been extensively covered here, with special attention to how the character Sailor Jupiter, inspired her voice actor. Despite criticisms of the latest Sailor Moon, the essential core message of the series has and remains valuable. Girl power, regardless of how feminine or tomboyish a girl is, is illustrated as something to be appreciated and proud of. While romance is one of many threads in the story, the series should be recognized for how progressive it was for its time and still has value in empowering girls to be whoever they want to be. Strong, willful characters who can be both independent and caring and a wide representation of different kinds of girls is what established Sailor Moon as an influential series in anime history.

Also worth discussing are the positive portrayals of women in some of Hayao Miyazaki’s work (which are highly recommended). Princess Mononoke from the film of the same name, Chihiro from Spirited Away, and Sophie from Howl’s Moving Castle are all very different characters, but with the same inner strength. Despite their differences in personality, behind a soft and quiet nature or a willful and proud one, and regardless of age and world setting, Miyazaki made his protagonists characters to appreciate and celebrate because they were not sexualized and minimized through romance. Rather, these characters were able to overcome insecurities and fears as a way to protect what and who they care about. Most importantly, these characters were able to grow from their experiences in relatable ways which inspires girls and women without telling them to change in order to fit society’s expectations of them.

So we arrive here, having started with a curious look at the portrayal of women in anime and manga and arriving at a sorrowfully inconclusive but hopefully informative end. While the discussion warrants a chapter in a book, a whole book, or shelves books devoted to the nuances of the topic, hopefully this has provided a useful insight in understanding that women in anime and manga is a complex, varied topic that grows and changes with time.

What other perspectives on anime girls and women do you want to know more about? Do you have any favorite female characters? Are the new stories moving in the right direction? What do you think?

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]