YL 33: The First Female Ham Radio Operators, and their Awesome Legacy

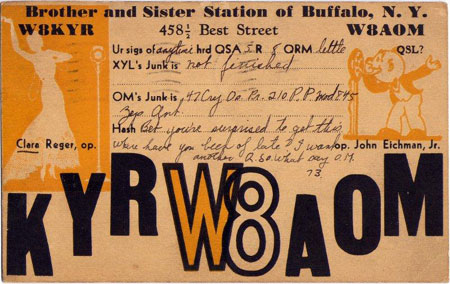

Love, sealed with friendship.

Historically, literacy—in its many forms—has given the marginalized a way to speak and participate in a system that previously prevented them from doing so. And while the printing press revolutionized the way writing was exchanged and shared with the world, the invention of radio as entertainment, emergency, and communication technology had a similar effect on oral storytelling. From this, ham radio, also known as amateur radio, was born as a subset of commercial radio. The appeal of communicating independently to others across the globe struck a chord with many people in the early 20th century—including women looking for ways to participate in war efforts, and connect with other women around the world.

Although enthusiasm for ham radio as the medium of choice for hobbyists, veterans, and emergency responders hasn’t waned much over the last fifty or so years, the hobby is making a strong resurgence as aspiring makers acknowledge radio’s contribution to the movement. Many hams consider amateur radio to be the original maker skill, requiring knowledge of electricity, geography and communication.

And it’s one of many mediums that gave women the chance to have a global voice—and they took it.

Calm the ham

For those unfamiliar with the subculture of ham radio, the title “ham” was originally used as a negative name associated with amateur operators who, without proper training, would disrupt professionals. Eventually, though, the name lost its negative stigma and is now used interchangeably with “amateur.” Regardless of someone’s amateur status, all operators must be licensed and complete a training program, through FCC regulations.

Female hams are called “YLs,” which is short for “Young Lady,” regardless of the operator’s age. While that seems simultaneously antiquated, cute, and patronizing, keep in mind that the ham radio subset of men is referred to as “OMs,” or “Old Man.” The largest organization for YL ham operators in the world is the Young Ladies’ Radio League, Inc. (YLRL), founded in 1939, which exists to encourage and assist YLs throughout the world to become licensed amateur radio operators.

Although amateur and commercial radio was heavily male-dominated, the response to the influx of women operators was—and still is—largely positive. In “The Feminine Wireless Amateur,” a 1916 article in The Electrical Experimenter, the writer says:

JUST because a man, Signor Guglielmo Marconi by name, invented commercial wireless telegraphy does not mean for a moment that the fair sex cannot master its mysteries. […]

Women seem to progress excellently in the engineering branches. Primarily this is so because her brain is quick of action, and moreover she usually will be found to have extremely well-balanced ideas as to proportions, so essential in designing. A wonderful imagination coupled to a number of other worthy faculties help to make a really fine combination, so that we find a steadily growing number of women architects, mechanical and electrical experts, radio operators, civil engineers, ad lib. What we need is more of them in the higher positions, where the square root and binomial theorem are everyday quantities.

That’s quite a positive—and progressive—perspective on women in science and engineering – especially for 1919. A 1931 article in the New York Times also remarked on this trend, saying that

The list of women obtaining licenses as amateur radio operators is increasing rapidly, the Department of Commerce said today, although there were only eight registered women commercial operators in the country. […] There are eighty-six women amateurs, compared with about 18,000 men operators.

This number has changed drastically since the 1930. And while there are now thousands of women worldwide with call signs, several notable women during the early 20th century set the stage for the new generations of girls finding a voice on the airwaves.

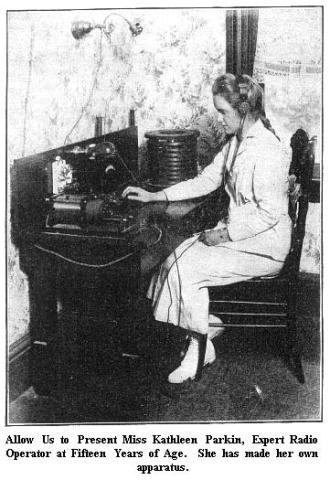

Gladys Kathleen Parkin

At just fifteen years old, Gladys Kathleen Parkin (1901-1990) received her professional ham radio license. Basically, this makes her a total badass, considering that she’d had her amateur radio license since age nine. She was featured on the cover of The Electrical Experimenter, and at the time was the “youngest successful female applicant for a radio license ever examined by the Government at that time,” according to a 1916 article in the San Francisco Chronicle. Parkin began her hobby at age five with her brother, and was the first woman in California to pass the first-class radio license.

Parkin’s call sign is 6S0, and she spent her life in the radio industry, developing a reputation for building her own equipment. Here she is, quoted in The Electrical Experimenter:

With reference to my ideas about the wireless profession as a vocation or worthwhile hobby for women, I think wireless telegraphy is a most fascinating study, and one which could very easily be taken up by girls, as it is a great deal more interesting than the telephone and telegraph work, in which so many girls are now employed. I am only fifteen. … But the interest in wireless does not end in the knowledge of the code. You can gradually learn to make all your own instruments, as I have done with my ¼ kilowatt set. There is always more ahead of you, as wireless telegraphy is still in its infancy.

Graynella Packer

At twenty-two, Graynella Packer of Florida became the youngest woman to become a wireless operator “on board an ocean-going steamship,” reads a 1914 article in the King Country Chronicle. Her experiences at sea gave her many stories that she later recounted to her friends and family. Although she technically wasn’t an amateur, her passion began as a hobby, and Packer had long been interested in the way electricity and communication worked on the open seas. She served on the steamship Mohawk from 1910 to 1911.

Olive Carroll

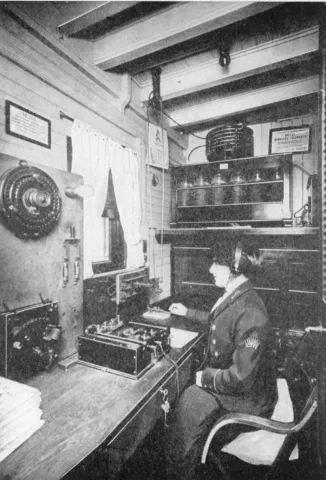

Canadian-born Olive J. Carroll had a passion for travel and exploration while growing up during the 1930s and 40s – and radio was her gateway to the world. Carroll’s interest in amateur radio began in high school, but she eventually turned it into her career and attended the Sprott Shaw School of Radio, where she earned her second class radio certificate in 1944. She was hired by the Canadian Department of Transport as an interceptor operator, and a few years later, when an opportunity opened on the Norwegian passenger freighter M/S Siranger, she accepted the position—having never before traveled farther than 500 miles from her home. Like Packer, Carroll was driven by a desire to explore the world by operating from the ocean.

In 1994, she authored a book about her experiences called Deep Sea ‘Sparks’: A Canadian Girl in the Norwegian Merchant Navy. The San Francisco Maritime Museum has recreated a ship’s radio room with the same equipment Carroll used during her time on the M/S Siranger.

Clara Reger

It’s impossible to talk about notable female hams without acknowledging the work of Clara Reger, who received her call sign in 1933 at age thirty-five. Reger had a long career as an operator, and managed disaster communications after WWII. Known for her exceptional Morse code skills, Reger spent much of her life teaching others how to become operators. She also received the Edison Award for teaching a fourteen-year-old boy without arms to send Morse code with his feet.

But Reger is also known for her signature salutation, which she created especially for women communicating with other women—the salutation ’33,’ which meant love sealed with friendship. Reger knew that to hear another girl’s voice on the other end was rare and special. What a gift, to find kinship with women, through the radio, across the ocean, across the globe!

YL 33 is considered sacred by female hams, and there’s a poem dedicated to Reger’s accomplishments and passion for radio communications. You can read it in full on the Young Ladies Radio League’s website, but here’s a passage:

There’s no real definition

But its meaning is known well.

It’s how a YL says good evening

To another friend YL.

Although these are just a few of the many women who used radio as their medium of choice, their stories as operators are fascinating and inspiring. These women are united in their mutual passion for exploration, technology and adventure, and that still holds true today for many female ham operators. If you’re interested in becoming a ham radio operator, consider joining YLRL, the Sisterhood of Amateur Radio, or the ARRL.

Ashley Hennefer, M.A., is a writer and researcher based in Reno, Nevada. She’s the founder and editor of The New Artemis, and is passionate about technology, travel, and the humanities.

Are you following The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]