Feminist Futures StoryBundle: Why We Still Need Feminist Science-Fiction

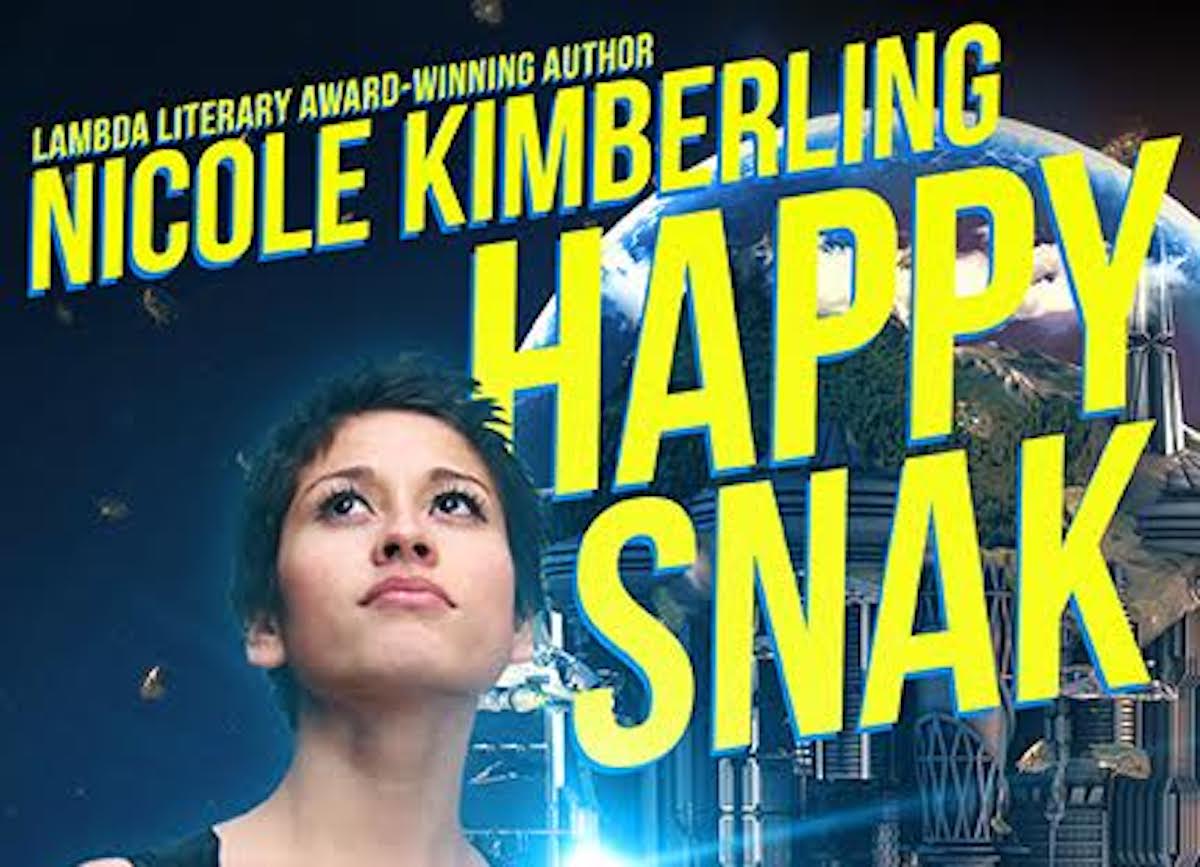

When Cat Rambo first approached me about including my novel, Happy Snak, in a StoryBundle, I thought it would be representing the “outer space” niche in a collection of genre-based comedies. So when I realized my story would be included in “Feminist Futures,” I was taken aback. Happy Snak is about a woman who owns a dinky snack bar in space. She fraternizes with aliens and refuses to comply with arbitrary regulations but is otherwise largely apolitical. Why, I wondered, would anybody consider this feminist? Then, thinking further, I realized that for many women, just being themselves and making (and spending) their own money is still considered a threatening and subversive act. (I’ve got my eye you, Quiverfull.)

Overall, I think feminist science-fiction gets a bad rap. Readers think of serious, soft-voiced women telling them off for 350+ pages. They fear being forced to engage in what might be described as “medicinal reading.” It’s okay. There’s been a lot of misinformation and alternative fact surrounding our kind of storytelling, but I’m here to tell you that you need not be afraid because, just like there are all kinds of women, there is all kinds of feminist science-fiction.

When contemplating writing this essay, I did the quintessentially feminist thing—I asked the other women in the bundle what they thought.

First I got some backstory from Vonda McIntyre: “In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the big argument in SF was whether SF had room for women. They meant as writers, as characters, even as readers. I don’t remember learning to read. The first thing I remember reading is SF/F (Waldo and Magic, Inc., by Robert A. Heinlein), so I took the argument rather personally. Most of my fiction is, on one level or another, a response to that argument.”

Providing proof of existence—being seen—is everywhere in the modern cultural dialogue. Though I was already a self-described feminist at the age of seven, I was a latecomer to the love of books (having only started engaging with the written word when it became clear that it impressed other girls). So by the time I got around to reading McIntyre’s books in the 1980s, women had gained a little more prominence in the genre in that female characters existed—mainly as side characters and romantic interests, the “plus ones” of the literary world.

Don’t get me wrong—I love romance and love interests in stories. Attempts to find romance with book-reading girls was the reason I’d started hanging around bookstores in the first place, but a “plus one,” no matter how delightful, is still just an accessory to the protagonist. Nobody wants to be a nameless “plus one” forever. Feminist science-fiction seeks to cast a woman as the lead character, regardless of what’s going on romantically.

For example, Janine Southard’s Queen and Commander is “a young adult novel where a bunch of guys are low-key in love with the same woman, but there are no love triangles to be seen. In fact, it would be beyond bad taste for any of them to do anything about it … and so they don’t. In a literary trope landscape that says, ‘Boys and girls can’t just be friends,’ Queen and Commander dares to avoid romance as the only thing a group of teens can focus on.”

Kristine Smith writes, “When I began writing Code of Conduct in the mid-nineties, I took part in more than one discussion about whether readers would be interested in stories with ‘strong female protagonists,’ even though they were being written at that time and had in fact been written for years. Decades. Those conversations still bubble up now, reaching out into television and movies—they seem to revive every 10 years or so. I wonder if they’ll ever end.”

And I wonder that, too. The argument begins to feel circular. Like the question was asked, “Is there a place for women in science-fiction?”

And the answer came, “Yes, dumbass, there is.”

But then the rebuttal boils down to, “And … so … what about now? Should there still be a place for women now? It’s been fifty years. Has that fad passed?”

As though women were just kidding about wanting to be treated as equals and would now settle down and let guys have all the good stuff again.

So when we acknowledge that all women are individuals, the field opens up to all kinds of different stories.

For example, clearly not all women are as interested in romance as I am, but that doesn’t mean that they don’t still want to read books. Rosemary Kirstein craves newness on every level: “The Steerswoman, and its subsequent sequels, has a constant background conversation with the expectations of genre. I made it a point to take every trope I could think of, and tried to re-examine it, reverse it, change it up, show the other side, flip it, spin it another way, or show what it might really mean. And the first trope I addressed was: A woman’s only real story is a love story. Screw that, I said to myself. I want an adventure.”

Whereas MCA Hogarth wants to flip the trope of the self-sacrificing female and let moms have it all: “An effective space marine has to be an alpha male, right? But why not an alpha mom? Moms are ferocious and tender in a different and interesting way, one that complements how dads (and men) are ferocious and tender. So here’s this mom, in power armor, leading the way a mom does. By protecting her (adopted) kids, while not cursing and not trampling people’s feelings and not taking any guff either. Helping people grow up is hard and takes discipline and toughness. It takes compassion too. Can you do that and kill aliens? Absolutely! You can make some alien friends along the way as well …”

Then what is the utility of this kind of narrative? What purpose does it serve, apart from to entertain? Why do we need it? Timmel Duchamp came to fiction through political action as both a women’s rights and anti-war activist. Her take? “I’d already had a lot of experience as a feminist activist (in what was then known as the Women’s Liberation Movement) that burned into me an awareness of class and cultural differences and how greatly most people longed to pretend they didn’t exist. So when I decided to create fiction showing how we might get from where we were in 1984 to a world in which everyone could thrive.”

And that’s the key: creating fiction as a model to a better reality that allows girls to dream—one in which women could choose to flourish in any way, not just ways previously forbidden to them by a male-dominated culture. In other words, science-fiction doesn’t have to be about resisting some rando patriarchy to be feminist. It only has to show women as equals and the result of that equality. In that way, feminist science-fiction could itself be a trope perpetually in the process of being reworked and adapting to the future that is being invented around it.

Editor Athena Andreadis addressed this while curating To Shape the Dark, a book of short stories showing “women heroes doing science not-as-usual. Yet while passionately pursuing their vocations, these women are also enmeshed in their kinships and societies, defying the too-common SF stereotype of scientists as socially inept or excused from familial and civic obligations because of their brilliance.”

We still need feminist science-fiction because we still need, and will always need, women’s thoughts and women’s ideas. And we need to keep the torch alight for that always-changing future girl who might be told otherwise.

Now that we’ve gone through a few decades of feminist writing, it’s tempting to use a “pass the torch” metaphor to end. But that’s inaccurate. We don’t pass the torch. We use our light to ignite another, because in a feminist world, it’s not necessary to extinguish one light for another to flourish. Rather, we share our fire so that everyone can be illuminated and seen. And we won’t stop until the whole world shines and shines and shines.

The Feminist Futures StoryBundle: https://storybundle.com/scifi is available until March 29th and features the following titles:

Starfarers Quartet Omnibus – Books 1-4 by Vonda N. McIntyre

The Steerswoman by Rosemary Kirstein

Happy Snak by Nicole Kimberling

Spots the Space Marine by M.C.A. Hogarth

The Terrorists of Irustan by Louise Marley

Alanya to Alanya by L. Timmel Duchamp

Code of Conduct by Kristine Smith

Queen & Commander by Janine A. Southard

The Birthday Problem by Caren Gussoff

To Shape the Dark by Athena Andreadis

Nicole Kimberling is a novelist and founder and editor of Blind Eye Books. Her first novel, Turnskin, won the Lambda Literary Award. Other works include the Bellingham Mystery Series, which is set in the Washington town where she resides with her wife of thirty years, and several other novellas and shorts. She also created and wrote “Lauren Proves Magic is Real!” a serial fiction podcast, which explores the lesser case files of Special Agent Keith Curry, supernatural food inspector. www.nicolekimberling.com.

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]