Tainted Love: Fetishizing Disability in Yaoi Manga Ten Count

Seeing the word ‘yaoi‘ (or ‘boys love’) will doubtless send off alarm bells in the minds of both feminist and LGBTQ folk alike who are familiar with manga and anime. Though it has its champions—self-defined as ‘fujoshi‘ (or ‘rotten girl’)—the genre has been heavily criticized for both its misogynistic representation of women (or total lack thereof) and the fetishizing of queer men that sadly seems to come part and parcel with most hetero-appropriation of LGBTQ culture. These are problems that, as a trash-loving fujoshi myself, I’ve written about in the past.

Though manga fans out of the fujoshi-loop won’t have heard of it, one of the genre’s most popular hits of recent years, Rihito Takarai’s Ten Count, has gripped readers with a dark and psychologically complex tale of sex, fear and exploitation. But, as well as making little effort to dodge the familiar trappings of yaoi, Ten Count adds yet more fuel to the fire by exposing readers to another problematic fetish in an already problematic genre.

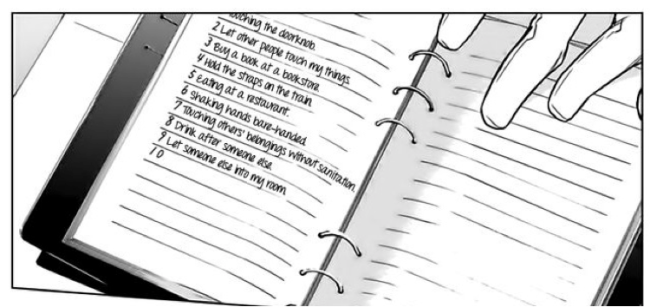

In the manga, we meet Kurose Riku, a counselor with a special interest in people with extreme mysophobia, also more colloquially known as “germophobia”, which, among other things, can make sufferers terrified of physical contact with others. By a chance encounter, Kurose crosses paths with secretary Shirotani Tadaomi and quickly recognizes the condition exists in him. He then seeks to cure Shirotani – or at least ease the severity of his condition to help him live a more normal life – through exposure therapy.

However, what becomes clear to us as the therapy progresses is that Kurose wants more from their relationship, which starts to inevitably cloud his objectivity as a doctor. Cloudier still are Shirotani’s own feelings towards his tall, dark and handsome doctor-friend, as it’s slowly revealed that the manifestation of his disorder during puberty seemed to repress the truth of his own sexuality.

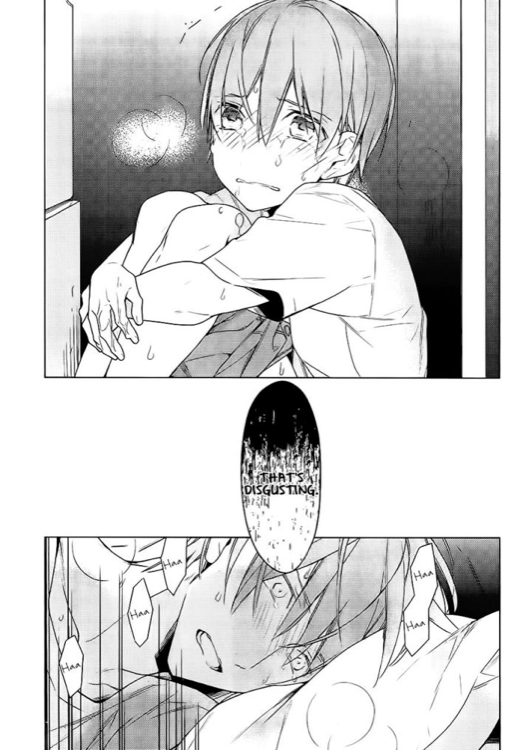

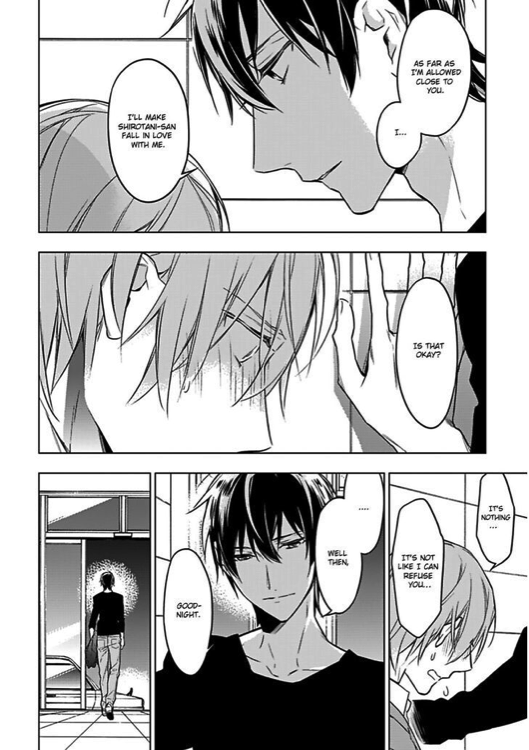

As the exposure therapy progresses and Shirotani begins to improve, Kurose becomes emboldened to reveal the romantic yearnings he’s kept secret from the sexually-repressed Shirotani from the start. This is where the psycho-sexual complexities of the story fully rear their ugly head. As Kurose pushes for physical intimacy with someone he knows fears it more than anything else, it becomes hard to untangle whether Kurose is attracted to Shirotani, or to his extreme disorder. Is it true love, or just objectification?

Like me, prior to reading this, you may have been unaware that fetishes for disabled people existed, but they absolutely do. “Devotee” culture, as it’s called, is a subsect of BDSM, a community who are aroused by the idea of caring for a person they view as vulnerable, similar to the desire that fat fetishists harbour to over-feed a plus-size person.

While there’s a valid argument to be made defending and preserving the depoliticised nature of sexual preferences, we can never escape the fact that – unless your partner is one of those haunted-looking sex dolls – there’s a human body with human feelings attached to whatever aspect of it you’re getting turned on by. So, how do disabled people feel about their disability being the source of someone else’s pleasure?

“It plays into a lot of complex social issues; from bodily autonomy for people with disabilities to inherently unequal power dynamics,” disabled writer S.E Smith explained in a post on the issue for FWD/Forward. She added that, as a member BDSM culture, she had no problem with fetishes, but that, “there’s a difference, for me, between, say, a leather fetish […] or a high heel fetish and a fetish for a particular type of body. There are also degrees of power play, and devotee culture, to me, feels like a very unsettling form of power play. […] Disability fetishism is not the only form of fetishism which focuses on fetishizing marginalized bodies. For example, racial fetishes are quite widespread. As are fetishes of children and teens. These bodies are already dehumanized in our society and culture; fetishizing them is extremely problematic because it adds to their dehumanization.” She went onto emphasize exactly why fetishes for body types are harmfully different than those for body parts. “A body is not something you can take on and off. When someone is done with a foot fetish scene, the heels can be put away. […] When you are done exploring power play, you emerge from the scene and return to a more equal state. You can’t do that with a marginalized body. When your body is someone’s fetish, you are an object. You are disempowered. All the time. You can’t escape.”

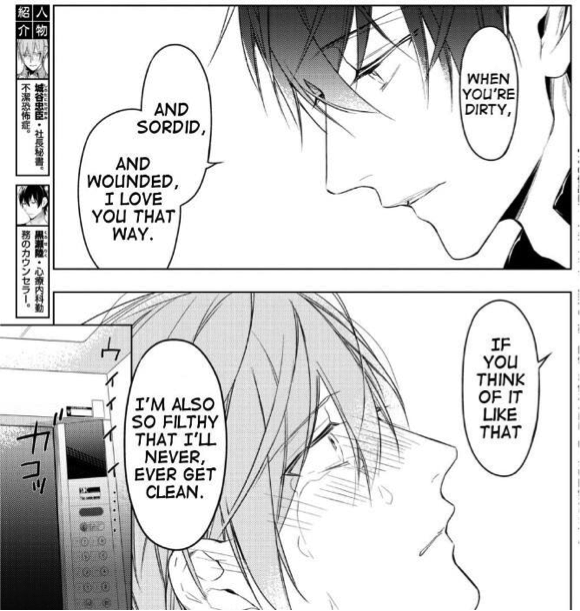

That last evocative line rings particularly true for a character like Shirotani. The crushingly inescapable nature of his disorder is actually well-represented by the manga, as is the conflicted mingling of both relief and loneliness he feels living in such isolated but controlled conditions, which seem to ring mostly true against this anonymous mysophobia-sufferer’s account. Kurose’s treatment of Shirotani, on the other hand, perhaps embodies more of a ‘perverted’ stereotype of a Devotee, as he pushes the boundaries of Shirotani’s phobia in both everyday and bedroom activities, constantly trying to read between the lines of what Shirotani’s words and body tell him – or whether there is anything to read between in the first place. He seems to revel in Shirotani’s conflation of being “dirty” in the literal sense with being “dirty” in the sexual sense, “Do you want to reject me, or be tainted by me?”, and allows his possessive nature to take advantage of the oppressive isolation Shirotani’s condition has imposed upon him. Shirotani often says he feels “paralysed” during their sexual encounters, both by his illness and virginal naiveté, the latter of which Kurose uses to infantilize him—”You’re like a child”—disempowering him further.

Though Takarai makes it increasingly clear as the story progresses that Kurose’s feelings for Shirotani run deeper than just a very specific sexual fetish, this insertion just feels like an excuse. While Kurose does indeed fulfill his pledge to lessen Shirotani’s suffering, that fulfillment comes at an exploitative cost. Where there should be mutual consent, there is forced dominance and subservience. Where there should be an equal partnership, there is someone in a position of power objectifying and preying on someone else’s perceived vulnerabilities.

Because Ten Count falls under the wider bracket of “Romance,” a genre that trains us to view everything in it through rose-colored glasses, we’re lured into glossing over unhealthier aspects of fictional relationships in favor of the nice, mushy fantasy that love–in any form–is a blemish-free cure-all, especially love “in spite of” something. But, once you put the glasses aside, all you can see is the ugly truth of a tale that, like E.L. James’ 50 Shades Of Grey series, normalizes abuse. Granted, Takarai manages to give her characters considerably more nuance than James managed to do for hers, but while this objectively deepens the reader’s urge to unravel the story’s complexities, it still detrimentally ignores the emotional concerns the disabled community have voiced about the disempowering nature of disability fetishizing.

Ten Count is still ongoing at the time of writing, so perhaps it’s unfair to judge it as a whole yet. There’s still potential for redemption if Takarai decides to add a more critical voice to the narrative. But, perhaps it’s also fitting that, in a story that forces its protagonists to face their deepest and guiltiest pleasures, we as readers–and fujoshi–are forced to face ours: the internalized homophobia of objectifying queerness, the internalized misogyny of seeking out male-dominated stories, and the internalized ableism of sexualizing power over those we perceive as weaker than us.

For more on disability fetishizing, I recommend these resources:

‘Queer And Disabled On Fetishization‘, Curve

‘How I Came To Terms With People Fetishizing My Disability‘, Vice

‘”Pretty Cripples” And The People Turned On By Disability‘, BBC News

(images: VIZ Media)

Hannah is a UK-based writer, illustrator, podcaster, trash-loving fangirl and part-time librarian (doing her best Evie from ‘The Mummy’ impressions). Follow her on Twitter here.

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]