I Can’t Stop Thinking About the First Published Kirk/Spock Slash Fanfiction

At Flame Con in August, The Mary Sue hosted a panel on the LGBTQIA+ history of fanfiction. Princess Weekes kicked us off with a background about how much that is literarily lauded from olden days—from the Aeneid to the works of Dante and Shakespeare and Milton and on and on—is essentially fanfiction, and we are continuing perhaps the oldest literary tradition of reshaping and retelling existing stories.

Then I gave an overview of the rise of modern fandom in regards to LGBTQIA+ themes. The consensus seems to be that slash fanfiction as we know it first emerged into the open with Diane Marchant’s 1974 Kirk/Spock story “A Fragment Out of Time.”

Marchant did not “invent” Kirk/Spock: the subtext and chemistry between the dashing Starfleet Captain and his stoic (when not in pon farr) Vulcan first officer was there onscreen for anyone who cared to see it, and Kirk/Spock stories, meta, and theories were already being traded between groups of Star Trek: The Original Series fans by letter in the 1960s.

Marchant’s story is recognized, however, as the first Kirk/Spock piece of fiction to be published for consumption beyond a closed circle of friends. The story appeared in the R-rated Star Trek fanzine Grup #3 in 1974. The Original Series had been canceled in 1969 after three seasons, but its wildly dedicated fanbase wasn’t about to let their favorite characters and Gene Roddenberry’s inventive universe fade into obscurity. They kept the ball rolling with letter-writing campaigns, zines, and conventions, and their tireless dedication was a big part of what would eventually turn Star Trek into a cultural phenomenon.

As someone who has participated in online fandom since I was about 12 years old, I’d heard of “A Fragment Out of Time.” But it wasn’t until I was researching for our Flame Con panel that I gave the story a close read and investigated the history around its publication and reception. Now I can’t stop thinking about “A Fragment Out of Time” and how far fandom and particularly fanfiction with LGBTQIA+ themes and characters have come since Marchant’s story in the ’70s.

First of all, its format is absolutely fascinating. Neither character is ever named, and there’s a gaming in the use of pronouns so that it’s never precisely clear in the text that it is two men having a romantic encounter. While the narrator of the story, who is being treated to some tender and then increasingly sexual caresses, is called “he” (it’s Spock), the second character’s actions are shown in an abstract that doesn’t require identification, or else referred to as simply “the other” (it’s Kirk, he of the “blond head”). Here’s an excerpt by way of example:

The pressure was… delicious. Well-skilled hands made long, swooping strokes from his knees up the inside of his legs to the upper thighs. Now, he could not prevent this, any more than he could stop a solar eclipse… even if he really desired to. It had been building all these years… no one set of circumstances was the cause… now; it seemed it had been inevitable from the outset.

The whole story is roughly 500 words—shorter than this article. An incredibly compact little thing to have created a sensation and to be seen as the forerunner of a fiction type for which there are now hundreds of thousands of fan-made works. Yet it kicked open a door that, I believe, will never be shut again.

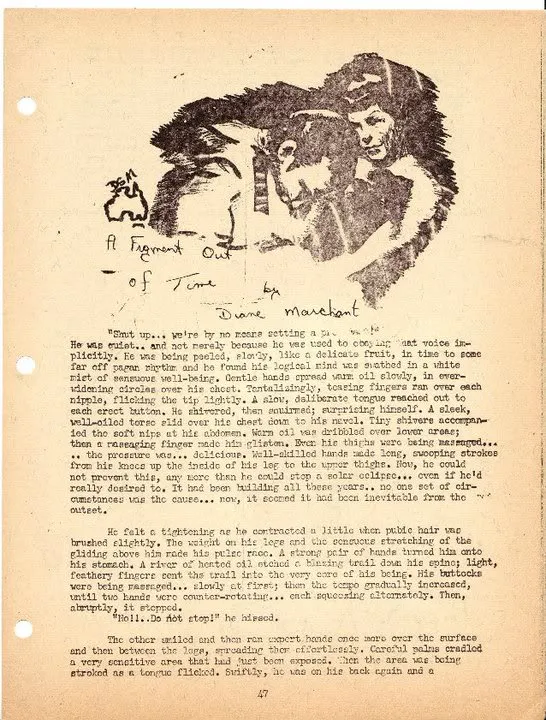

While Marchant’s text mostly obscures its characters’ named identities—perhaps out of fear of legal ramifications—her intention for its interpretation was hardly a secret. “A Fragment Out of Time” was published in Grup with a drawing by Marchant herself at the top that showed Jim Kirk and Spock locked in an embrace.

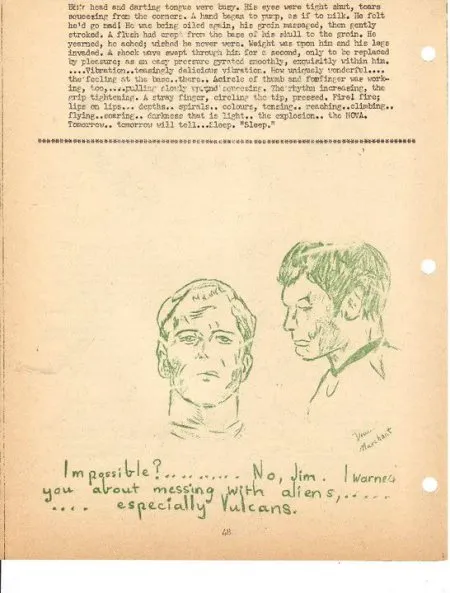

Additionally, as Tansy Rayner Roberts writes in an excellent essay on the piece, “a cartoon underneath the final page of the story shows Bones saying to Kirk: ‘Impossible….. No, Jim. I warned you about messing with aliens…….. especially Vulcans.’ (The look on Kirk’s face in the cartoon implies he has just been told about the existence of slash fiction. Oh, sweetie.)”

Roberts notes:

In an interview with Diane shortly before she died in 2007, she modestly refused to take any credit for the Kirk/Spock phenomenon:

“Really, I had nothing to do with the initial concept, as it was there unfolding on our screens as we watched our beloved Star Trek. Me, well—I just accepted a challenge and attempted to subtly present the idea deftly (with slight humorous overtones) as a scenario which most could find acceptable at that time.”

Marchant’s story was greeted with “a firestorm of controversy” and sparked years of debate within Star Trek fan circles. But it also set a precedent. Kirk/Spock was out in the open, and it would go on to become the granddaddy of slash, soon generating its own dedicated zines, art, and merchandise, and becoming such a standard in the world of male/male subtext found in media that even your most fandom-averse friends have probably heard of it.

I spend a lot of time shaking my fist at younger Mary Sue writers who refer to the pairing as “Spirk,” a portmanteau that emerged in the wake of the Chris Pine-led reboot that feels like blasphemy. It was the Kirk/Spock pairing that literally created the term “slash” due to the punctuation between their names. (In the long, long ago, stories featuring heterosexual relationships or “general” friendship/action stories used an “&,” to denote the main characters involved, while Kirk/Spock established that slash mark, which is now the standard across the board). Spirk! Heathens, respect your elders.

“Spirk.”

That being said, with all respect to Diane Marchant, “A Fragment Out of Time” is very much proto-slash when compared to the stories available to us today on sites like Archive of Our Own and Tumblr, and before that, on Usenet groups, mailing lists, online archives, the dreaded fanfiction.net, LiveJournal, and Dreamwidth.

Today, there is everything from the most explicitly hardcore stories exploring every possible romantic permutation to sweeping works of epic literature featuring popular characters as queer in stories that can run into novel-length works. Queer relationships and romance are increasingly part of mainstream publishing as well—and no few authors got their start in fanfiction.

Reading Marchant’s story now feels profoundly meta: it has become, indeed, a fragment out of its time. I couldn’t be happier that the story came to be—and that we have moved into an era less than fifty years later where reading characters as queer is no longer an idea that is considered atypical and in many cases has entered the zeitgeist.

You can read more about the history of “A Fragment Out of Time” at Tansy RR’s site and at Fanlore.org. Marchant’s story was reproduced for posterity on fanfiction.net and can be seen in its mimeographed glory below.

(images: The University of Iowa’s Hoover Collection, Paramount)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]