Five Classic Stories (and Their Retellings) That Challenge the Patriarchy

My parents’ house was full of books. Chronological in the living room (Aristophanes to Alexander Pope, Arthur Conan Doyle to Joseph Campbell), alphabetical by subject in my English professor father’s office, a sturdy bookcase in the hall between my sister’s and my bedrooms filled with classics from my mother’s childhood.

These were the stories that shaped me and my early view of women’s place in the world, that provided role models for the woman I wanted to be and gave me my first inkling of sex and relationships. Reading them now with grown-up eyes, I am struck by my bookish heritage of strong women—and also how those women clamor to speak in their own voices.

Here are five classic stories that challenge the patriarchy and how they have been reimagined by a new generation of storytellers to re-focus on the heroine’s journey.

The Odyssey by Homer

My introduction to the Odyssey was D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths. The gently couched stories of rape went mostly over my head, but even as a child I vaguely recognized that the abducted princesses and ravaged nymphs, the daughters sacrificed to gods or fathers, suffered in comparison to the sword-wielding heroes. Women did not go on adventures. But the vibrant illustrations brought the goddesses—warrior Athena, independent Artemis, vengeful Hera, all distinct and oddly human—to vivid life.

I was in college before I read Homer. The majority of women in his epic poem live in the margins of the heroes’ journey: mothers, muses, or monsters, there to inspire and sometimes simply to endure. Even resourceful Penelope, foiling her suitors during Odysseus’s long absence with her weaving and unweaving, is holding out for her husband’s return.

Madeleine Miller’s Circe (2018) puts a female character firmly in the center of the narrative. Circe—famous in Homer’s tale as a predatory female who transforms Odysseus’s men into pigs—here is a girl yearning for human connection and motivated by the sailors’ sexual assault. At one point she observes, “Humbling women seems to me a chief pastime of poets. As if there can be no story unless we crawl and weep.” In Miller’s retelling, Circe does not crawl, she sings, gradually discovering her power, creating a family, and claiming the full mortal life she craves.

Little Women by Louisa May Alcott (1868)

I was ten years old when my grandmother gave my sister and me a copy of Little Women. She probably figured it was an appropriate story for girls. Which it is. Sisters Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy aren’t sidekicks or sweethearts, but the heroes of their story. Little Women follows their different paths to adulthood. I wanted to be Jo, the center, star, and interpreter of the narrative. But I wondered, was there more to the story than Jo (or even Louisa May Alcott) told us?

Alcott’s story was originally published in two parts, Little Women (1868) and Good Wives (1869). By the end of the second book, the March sisters are all married or dead, their artistic ambitions largely compromised in service to family life. This was the 19th century, after all.

I’ve written before about the challenges of reinterpreting a classic. Several recent novels strive to keep the heart of Alcott’s story (family, friendship, and the conflict between art, love, and money) while reimagining the sisters’ journey. My retellings, Meg & Jo (2019) and Beth & Amy (2021), give Louisa May Alcott’s iconic characters fresh voices, more agency, and empowering choices options, putting their relationship and career struggles in modern times and bringing the sister nobody likes and the dead one out of the shadows.

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte (1847)

My tweenage heart thrilled to Jane Eyre’s extravagant emotions and Gothic drama. I identified with outcast, powerless orphan Jane (never mind that I had two living parents and no need to make my living as a governess), who makes a passionate case for her own equality. “Do you think, because I am poor, obscure, plain, and little, I am soulless and heartless?” she demands of her aristocratic employer Rochester. “You think wrong!—I have as much soul as you—and full as much heart!” Heady stuff.

After Rochester’s disastrous first marriage comes to light on their wedding day, Jane resists his attempts to make her his mistress. She stands against his wealth and his will until, after privations and visions and possibly divine intervention, she is ultimately triumphant.

It took Jean Rhys’s postcolonial prequel, Wide Sargasso Sea (1966), to make me see how Jane’s happy ending comes at the expense of Rochester’s Creole first wife, the “madwoman” in the attic. The tragic ending is dictated by the events to come. By giving voice to Antoinette (renamed Bertha by her husband, in a heartless erasure of her identity), Rhys illuminates not only her struggles in a white, patriarchal society but Jane and Rochester’s own power dynamic.

Persuasion by Jane Austen (1817)

Compared to opinionated role model Lizzie Bennett, Jane Austen’s Anne Elliott seemed pretty lame to younger me. Persuaded to sacrifice love and happiness by giving up the ineligible Wentworth, Anne becomes her family’s caretaker/doormat. Not an obvious feminist icon, in other words. It wasn’t until I was older that I realized Anne wins by remaining true, not only to Wentworth, but to herself.

At the end of Persuasion, Anne defends women against the charge of inconstancy: “Men have had every advantage of us in telling their own story.” It is this conversation—Anne at last speaking out, finding her voice—that compels Wentworth’s renewed proposal and leads to their happy ending.

In Sonali Dev’s Recipe for Persuasion (2020), it is the mother, Shoban, who pushes back against the patriarchy, putting her own ambition and desires before the needs of her family. Because of her mother’s perceived abandonment and her father’s suicide, their daughter, Ashna, internalizes the pressure to sacrifice her own hopes to preserve her father’s legacy. Dev gives both women equal voice, exploring their choices without apology as they pursue their dreams and find their way back to a relationship.

The Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum (1900)

L. Frank Baum’s mother-in-law was Matilda Joslyn Gage, one of the founders of the National Woman Suffrage Association. His marriage vows apparently omitted the traditional injunction to “obey,” the local newspaper reporting, “The promises of the bride were precisely the same as those required of the groom.” Baum’s Oz, like his life, is populated with strong women—the witches and Ozma, the ultimate ruler (and briefly a boy).

Gregory Macguire’s masterful retelling, Wicked (1995), is the witches’ journey. Dorothy, when she appears, is a very ordinary girl, her “weapons,” according to the witch Elphaba, “inane good sense and emotional honesty.”

Maybe Dorothy’s ordinariness is why I loved her. Hidden away on the floor of my room between the bed and the wall, I could imagine myself as that little farm girl from Kansas, sometimes tearful but resilient and kind, whisked away to another world armed with nothing but a soft heart and kick-ass shoes.

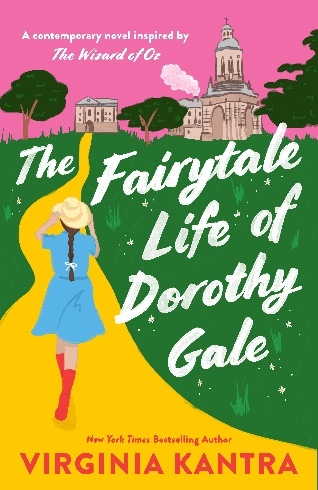

In The Fairytale Life of Dorothy Gale, I envisioned Dee as an Every Woman, a writing student at the University of Kansas who is heartbroken and humiliated when her relationship with an older faculty member is exposed in his salacious bestselling novel. She runs away from the storm of Internet trolling to attend a one-year writing program at Trinity College Dublin, embarking on a heroine’s journey, encountering friends and mentors. Dee’s former lover minimized and objectified her through the lens of the male gaze. In the Emerald Isle, Dee finds her voice. Along the way, she not only learns to take control of her own story, but—like the original Dorothy—helps her friends achieve their dreams, too.

Dee’s writing advisor in Dublin, Maeve Ward, tells her, “Women who tell the truth are always called witches.” Reimagining classic stories in the light of our own experience and emotions, we can give expression to our silenced or neglected voices. Like Circe or Dorothy, when women speak our truths as human truth, we find our own power.

Virginia Kantra is the New York Times bestselling author of almost thirty novels. She is married to her college sweetheart, a coffee shop owner who keeps her well supplied with caffeine and material. They make their home in North Carolina, where they raised three (mostly adult) children. She is a firm believer in the strength of family, the importance of storytelling, and the power of love. Learn more online at http://virginiakantra.com.

Her latest novel, The Fairytale Life of Dorothy Gale, is a contemporary retelling of The Wizard of Oz.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]