Unsung Heroines: The Forgotten Female Spies of World War I

“Female spies.” The word conjures up images of James Bond villainesses in slinky dresses, purring double-edged one-liners through a haze of cigarette smoke as they coax information out of their helpless marks. Spying wasn’t really perceived as glamorous until after the Bond myth took hold, but women have always been essential parts of the intelligence business, simply because women could often eavesdrop, run messages, or pass information without being noticed and suspected as men would have been. World War I’s most successful spy ring was called the Alice Network, and it was run by a woman. Her name was Louise de Bettignies, and she was known as the Queen of Spies.

Louise was born to an impoverished manufacturing family in France. Well-educated and multi-lingual, she took the Jane Eyre option like many educated-but-broke women of the day, and supported herself as a governess for various noble European families. Louise was in France when war broke out, and on a visit to England soon afterward she was recruited by British intelligence, who were not slow to notice her quick wits and her fluency in French, German, and English. Louise returned to northern France, now occupied by the Germans, and quickly set up a network of sources throughout the region: men, women, and even children who would collect information on the enemy, everything from troop numbers to train schedules to artillery placements. Louise, on the move constantly through the region, compiled her sources’ information into reports which she passed back to England.

The risks were appalling. The Germans did not hesitate to shoot those suspected of espionage, and mounted frequent checkpoints to catch spies. Louise employed a handful of differing identities, passing across borders with coded messages hidden in a variety of ingenius ways: between the pages of a magazine, rolled up inside shoe heels or umbrella staffs, wrapped around hairpins or the band of a ring. She knew exactly how to play the guards, whether by playing the witless female chattering gossip, or whether taking so long to fuss with an armload of packages that she was waved through in exasperation without being checked further. “They are too stupid,” she once laughed. “With any paper one sticks under their nose and plenty of self-possession, one can get through.” Louise also crossed borders on foot and in stealth when necessary, making grueling nighttime hikes across heavily mined and search-lighted borders already littered with the bodies of refugees who had not made it to safety. Even when she saw a fleeing pair blow up before her eyes as they stepped on a mine, Louise remained undeterred from her work. Her poise, humor, and way of shrugging off peril was remarkable. “Bah! I know I’ll be caught one day, but I shall have served. Let us hurry, and do great things while there is yet time.”

Her efforts paid off: her network was astoundingly successful, her intelligence so reliable and so fast-moving that British military men gushed like teenage girls at One Direction concert. They called Louise de Bettignies “A really high-class agent” and wrote “I cannot speak too highly of the bravery, devotion, and patriotism of this young lady.” And Louise was not the only woman facing incredible danger to serve her country in the war. Red Cross nurse Edith Cavell smuggled many wounded French and English soldiers to safety from Belgium; young Gabrielle Petit led downed pilots from behind enemy lines; a Belgian vicomtesse ran a successful organization for passing information and people into the Netherlands. And ordinary women risked themselves, too, like the teenaged Aurelie le Four who worked for the Alice Network as a local guide for Louise’s spies.

The price that was paid for such courage could be horrifying. Edith Cavell and Gabrielle Petit were arrested, condemned for espionage, and shot by firing squad. The vicomtesse was arrested and spent three grueling years in Siegburg prison. Young Aurelie le Four was raped by German soldiers when returning from guide duty after curfew, but still continued to serve the Alice Network . . . and when she became a nun after World War I, she was still standing up to German soldiers thirty years later, when the next war came to her doorstep looking for the Jewish children under her care. Courage continued undaunted, from the Queen of Spies to even the youngest of her couriers.

And what happened to Louise? Did the Queen of Spies survive the war, or face a firing squad? Read “The Alice Network” to find out!

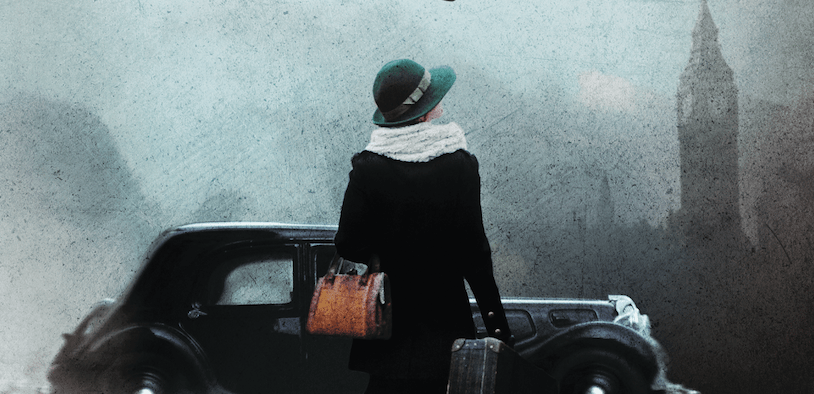

(image: HarperCollins)

Kate Quinn is a native of southern California. She attended Boston University, where she earned a Bachelor’s and Master’s degree in Classical Voice. A lifelong history buff, she has written four novels in the Empress of Rome Saga, and two books in the Italian Renaissance detailing the early years of the infamous Borgia clan. All have been translated into multiple languages. She and her husband now live in Maryland with two black dogs named Caesar and Calpurnia.

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]