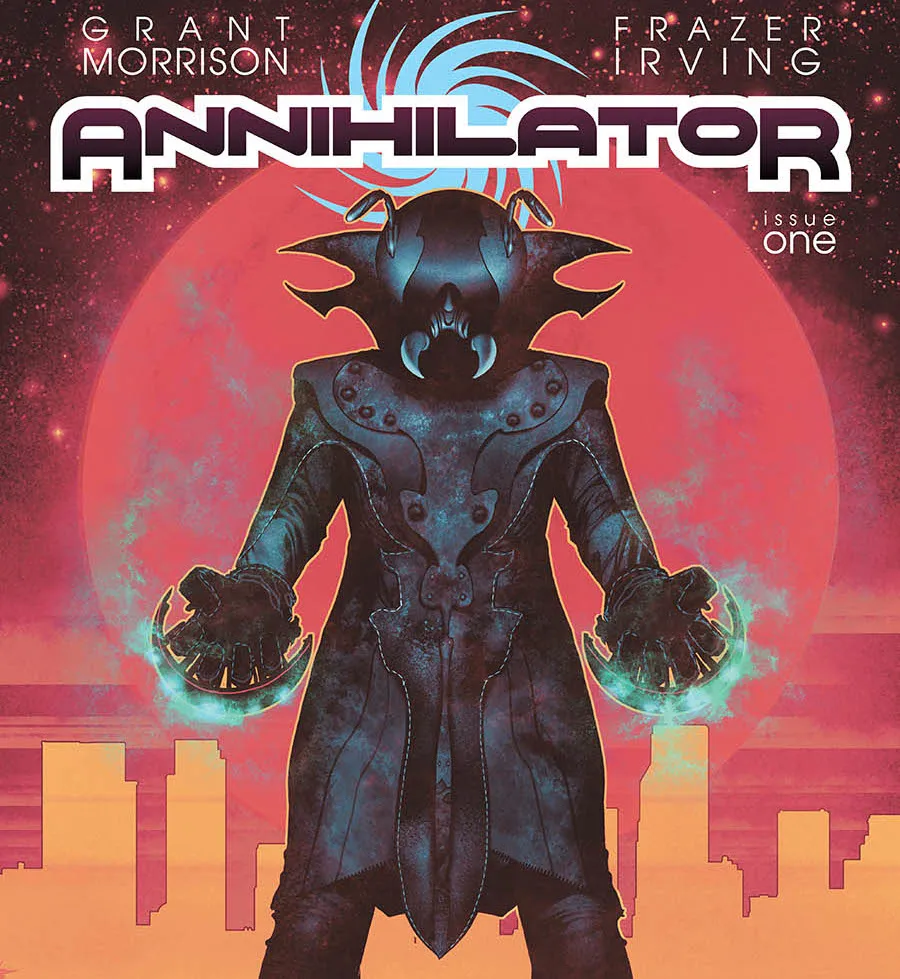

Annihilator might sound like the title of a deliberately over-the-top super-anti-hero comic or a metal band (actually, it is a metal band), but the tale in Grant Morrison and Frazer Irving’s six-part Annihilator graphic novel is about so much more. We spoke to Irving (Necronauts, Judge Dredd) to get some insight into the unique book.

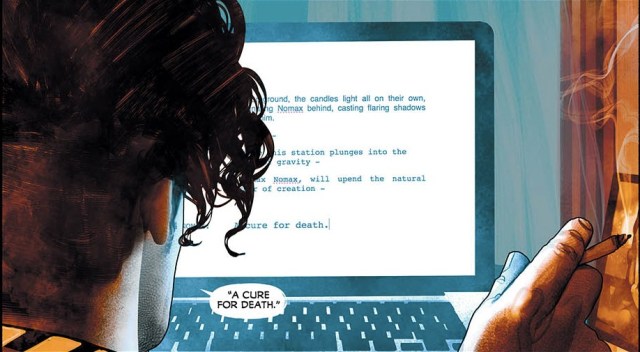

Annihlator tells the story of nearly washed up screenwriter Ray Spass (pronounced “space”) as he struggles against his own demons to complete a screenplay that will save his career. Things get complicated when he’s forced to team up with the character he’s created, who has been marooned on the edge of a black hole, to save the Universe. It’s a much darker take on the concept of a fictional character coming to life than what you’d normally expect.

We’ll have a full review of issue one tomorrow, but for now, take a look at what Irving had to say about building the weird world of Annihilator through art.

The Mary Sue: Annihilator is a really interesting book. It seems like everything in it is kind of circular in logic and bends back in on itself. You’ve got the fictional character, Max Nomax, coming into the real world, and their names, like Ray Spass (note: pronounced “space”), even kind of tie into that. What’s it like putting something like that together?

Frazer Irving: I try not to think about it too much. There’s a lot of wordplay in the script, like the pronunciation of Ray’s name is “space” as opposed to “spass.” I think some of that could be relevant to the overall themes. Some of it might just be fun on the writer’s part. I can’t intellectualize it too much, because then I’d go crazy, so I tend to just read the script and allow it to seep in under the surface, as it were, as I’m drawing. As with every good story, the art which I’m then making takes on a life of its own derived from my experiences reading the script.

So if you can see the circular logic in there when it’s all said and done, then that means it’s a successful project.

TMS: When you look at the artwork for LA or the outer space setting, is there a different approach that goes into each?

Irving: There’s different color coding for each of the different worlds. It’s not meant to be particularly blatant—just a preference for certain types of hues and an exclusivity with specific colors in each world. But I try to kind of blur that as the story goes on, because like you say, this whole playing of the life imitating art or art imitating life aspect to the story—part of my job as a storyteller and the colorist is to kind of convey that with background elements and stuff like colors and hues. So I did have a plan going in. As the story is coming to a close, I’m noticing the artwork is morphing quite happily to suit Grant [Morrison, the writer’s] themes.

It’s almost like we planned the entire thing—with a degree of improvisation and collaboration—so that’s a bonus.

TMS: How does your working process with Grant Morrison go as far as coming up with character designs and putting different ideas back and forth to each other?

Irving: At the beginning, there was some discussion regarding what the characters should look like, and we were coming at it form different viewpoints, so we kind of collided at some point and merged our ideas. Then once I started drawing the story parts, Grant would suggest the most fantastic and unbelievable things with his words, but one place to start off is processing a lot of the themes and ideas and action through my head. What appeared on the page was a mutation from that, so you’d say.

It’s a sign of a good collaboration when the writer can inspire the artist to draw things that are different—to exceed the initial impression of what should happen on the page. So I’m just putting that down to the fact that this story does something to inspire all the crazy visuals in it.

TMS: The book is very much about the whole Hollywood scene and what it’s like to be in LA and the weird vibe there. What was it like trying to capture that in art?

Irving: Well, there was the invitation to go and spend some time in LA trying to get a feel for being there myself, but I declined, preferring to go a bit more impressionistic route, where I would take verbal cues in the script like adjectives, nouns, certain music, films, and cinematography from people who’d captured their interpretation of LA. I put it all through the whole kind of thought grind, and tried to put my interpretation on the page, because I knew I’d never be able to capture LA properly.

I’d have to live there to really capture the nuance, so I thought, “This is a story that’s about fiction about fiction about a world of reality and fiction. Why not create a world that is, as you say, unstable and flexible as the personas of the characters within it.” Grant told me I captured the lighting quite well, which I think is always encouraging, because if you capture the skylight of a dawn anywhere in the world—if you can capture that particular light, you’ve got the location nailed. I’m kind of happy about that.

TMS: Yeah, I’ve never lived in LA, but that kind of orange, late-afternoon feel that it has to it definitely seems very Hollywood to me from an artistic standpoint.

Irving: Excellent.

TMS: I’ve only gotten to read the first issue, but I’ve seen that Grant has said that it deals a lot with the treatment of women in Hollywood culture. What can you tell me about where the book goes with that?

Irving: I’d be wary of placing too much emphasis upon Grant’s comments about some of the subplots and themes. It could be mistaken as being a manifesto, which it isn’t. It’s just part of the background and the plot details. I think one of the things that both Grant and I are aware of is that in popular fiction, women have been relegated to very stereotypical roles, and we’ve accepted and never questioned it until recently, and as artists, it’s our responsibility to try to show a broader palette of humanity.

Especially in comics, I think women have been portrayed in very stereotypical ways, and a lot of that comes from the fact that it’s influenced by what comes out of Hollywood. So Grant’s experience—with his knowledge of what goes on in that city—he’s described personality types and events, and I’ve just taken it on board in my own little way without actually having done these things. So we have a range of nihilistic, hedonistic prostitutes all the way down to almost Nun-like figures of quiet introspection. We have superheroes. We have witches—we have every aspect that humanity could possibly manifest itself in, either male or female. We’d like to try to imply that with the definite, visual interpretations of these characters.

Maybe I’m reading too much into it, but that’s what I think of when I’m designing these characters. They all have to have a history, and I think Grant is implying that some of these characters have been damaged, and so I’m trying to convey that with the subtlety of line as opposed to blatant drawing of scars, etcetera.

TMS: That’s good to hear, because of a lot of the time, that kind of diversity—even when it does make it into fiction—it’s not always handled with a lot of care.

Irving: [Chuckles] Yeah.

I find that there is a disturbing degree of tokenism in terms of all aspects of modern culture at the moment. I think that well-intentioned attempts to correct certain imbalances, there have been some rather ham-fisted attempts at doing so, which I think have been more damaging than encouraging. Then they set up a new stereotype, so when I’m drawing these characters in Annihilator, I’m not actually thinking about these issues. I’m just thinking about the character, and the influences of the world around me should’ve been absorbed over the past 43 years and will be filtering through my blood and into my brain, and so doing it that way as opposed to spitting out one of those—you know, those books where you can exchange the head and the hair types to kind of invent different types of characters.

It’s more instinctive, I think, and a lot of that comes from the characters that Grant writes. So, his characters are dark and disturbed, and the drawings all eventually become dark and disturbed, which is how it should work, I think.

TMS: Does working on something without big name characters—embarking on your own with this small run of a book—does that give you more freedom to explore those characters?

Irving: Oh, certainly. The first stories I drew professionally were self-contained stories for 2000 AD and so, from the very beginning, inventing worlds for short runs of stories has been my thing. It’s immensely liberating in the respect that I can choose the language to communicate to the reader—I can decide the colors and the shapes, and the more I do that, the better I get at it, and the more distinctive the work can become.

However, the appeal of working with the corporate-owned characters and the popular ones—the famous ones, should I say—is the fact that you know you have a ready-made audience, so they already come in with preconceptions, and there’s already some degree of creative conflict awaiting. A battle, as it were.

With an independent project such as Annihilator, we always have to start that from the ground up. So I get more freedom to muck around and draw what I want, but I know that it’s going to have to be more intense to attract the attention of the reader, because we have to tell them the rules of the story within the first issues. Whereas in something like Green Lantern, everyone already knows and you can just focus on other aspects, and so there is a trade-off. For the moment, I’m enjoying the world-building.

TMS: They seem to have a lot of similar issues. Spass has a picture of a woman on his desk, and Nomax is trying to bring his girlfriend or ex-girlfriend back from the dead, but I’ve only gotten to read the first issue. Where does that go down the line?

Irving: Well, I can’t really tell you what happens there without giving away plot details. I don’t actually know the final conclusion yet. The last part is still a mystery to me, which I’m eagerly anticipating, but I think the idea of their lives reflecting and echoing each other—a lot of that deals with the idea that the creator is reflected in every aspect of its creation. So a computer programmer’s personality would be somehow imbued in the coding or the choice of lines or design of the shell, and with Annihilator, I think this idea is that one of them is the creator of the other. It’s implied, I think.

It’s taken to that degree where this is essentially God making man in his own image quite literally. I think that’s certainly what it’s meant to be implying. That’s what I took from it when I read the script to begin with. Once we go further into the story, though, it does have more options for interpretation on that idea. And the dead girlfriend thing is kind of a sticking point, because they presume it’s the same situation, but there might be more to it.

—

Annihilator‘s first issue is available from Legendary starting Wednesday, September 9—tomorrow.

Are you following The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Published: Sep 9, 2014 06:45 pm