Gone Home Is The Story Exploration Game You’ve Been Waiting For

Review

It’s just a house. That’s all the game is, a house full of receipts and cups and boxes of tissues. Mundane and ordinary. You can walk around the house. You can pick things up, turn them over. You can paw around drawers and cupboards. You are alone. You are unguided. You can take all the time you need.

There’s a lot to uncover in Gone Home, the inaugural title by indie studio The Fullbright Company. Love, loneliness, secrets, desperation, sexual identity, growing up, acting out — it’s all there, hidden under beds and shoved into closets. I saw my childhood in there, and my adulthood, too, and the messy, complicated things I feel toward my family. It left me feeling raw, and clean, and quiet.

It’s just a house. It made me cry.

The year is 1995, and twenty year old Katie has just returned home from a year abroad. Not that the house is a home she knows. Her parents moved while she was away, and the house is as unfamiliar to Katie as it is to the player — after all, you are one and the same. No one is there to greet you. The door is locked. The house is empty. The only acknowledgment you are given is a note written by your younger sister, Sam. She apologizes for not being there. She asks that you not go digging around for answers. She says she’ll see you again one day.

And that’s it. There’s no quest log, no directions, no arrow pointing you toward something of use. Gone Home hinges on the assumption that curiosity alone is enough to drive the player onward. It certainly was for me. The farther I went into the house, the more anxious I was to learn what had happened there. Why had no one been there waiting for me? Was Sam hurt? Were my parents hurt? Was I in danger? Was I really alone? A storm raged outside, drumming on the windows and making the TV spit static. As I tore through every shelf, checked under every pillow, I found myself hoping for Katie’s parents to walk through the door and offer some answers. I was desperate to find a family I had never met.

Through nothing more than everyday objects and audio clips from Sam’s journal, Gone Home managed to make me care deeply about characters that were notably absent. It is striking how much can be learned about a person by what they choose to leave out on the counter, and what they tuck away in a dresser drawer. The game finds an elegant solution to an obvious problem — you don’t know who Katie’s family is, but she would. The gap is bridged by a subtle change in the UI text. An unfamiliar object will prompt text such as “grab plate” or “put back,” while others display recognition: “Oh, Mom’s old work mug,” or “Hey, that’s Dad’s first book.” It’s a clever trick, and it works remarkably well in blurring the lines between Katie’s experience and your own. Equally apt was the choice of time period, as I imagine that most of the people who play will be old enough to remember the ‘90s. I may not have had the exact same jeans or magazines or soap dispensers as the ones Katie finds, but I had ones like them. The approximation was close enough to get my nostalgic synapses firing.

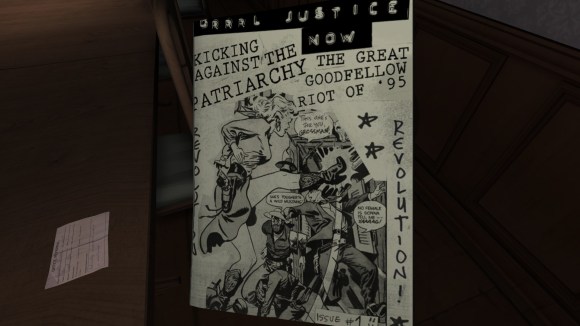

What hit me afterward was that Katie’s emotional arc took place not in the game, but in me. I felt sympathy, and a little bit of shame, when I found the rejection letters addressed to her father, the crumpled manuscript pages on the floor, the bottle of whiskey hidden in the corner. I felt awkward when I found her mother’s copy of a book entitled “After The Honeymoon: Rediscovering Your Spouse Personally, Spiritually, Sexually,” because, ugh, parents. But most of all, I felt for Sam, who reminded me painfully much of myself at that age. The similarity was uncomfortable, but in a way that pulled me in. I felt kinship through her belongings — classroom notes full of silly inside jokes, scribbled cheatsheets of Chun Li’s combos, X-Files VHS tapes with handwritten labels. She writes melodramatic adventures about her own original characters — Captain Allegra and the First Mate — and is exploring riot grrrl culture with all the innocent, reckless enthusiasm of a suburban teenager. My adolescence came a few years later than Sam’s, but I recognized it all the same, and the remembrance was bittersweet. As much as I wanted to tell her that there is life beyond seventeen, that she’ll grow past the things she thinks she can’t live without, I knew that she wouldn’t have listened, anymore than I did.

Bear with me while I make a brief segue. A few months back, I replayed Myst, the first game I fell in love with, alongside my brother, who had been too young for it back in the day. “God, slow down,” I said, as he darted around the Stoneship Age. “You’re missing the best part.” He glanced over the ornate bedroom. “What?” he asked. I met his eyes with earnest. “There’s stuff in the drawers.”

My love for environmental storytelling has been well nourished over the years, as games have become ever more layered and realistic. But a richly detailed environment is a component of modern games, rarely the game itself. Dear Esther and Proteus were all about the visuals, sure, but in those I was a visitor, not an inhabitant. A preferable experience, for me, was the more active exploration of games like Dishonored and BioShock Infinite, where I was free to rummage through houses and hidden rooms. As much as I enjoyed the combat in those games — and believe me, I did — I found myself wondering what BioShock Infinite would’ve been like if it had stayed in the same vein as that introductory stroll through Columbia, free of weapons and aggressive mobs. Could you have a game like that? Could you have a game where all you did was walk around and touch things? What would it feel like? Would it even work?

I don’t have to ask those things anymore. Gone Home is that game. I think I’ve always wanted to play something like it.

I honestly thought I might get bored. I was planning to play through in sessions, just a little bit at a time. I mean, how long can you spend turning tissue boxes upside down? Hours, it turns out. The attention to detail is exquisite (after I started drawing BioShock comparisons, I was amused to learn that The Fullbright Company was founded by alums of that franchise, which explains a lot). That alone was enough to lock me in. I couldn’t pull myself away. I had to force myself to slow down as my search for answers got more and more frantic (I knew Katie would be acting the same at that point, too, turning drawers upside down, running in whatever direction the latest clue sent her). I played the whole thing in one night, and the next day, after the warm, tight feeling in my chest had ebbed, I went back in, carefully retracing my steps, savoring all the care that went into making this beautiful, beautiful thing.

As is necessary for a game wholly dependent on visuals, Gone Home runs like a dream. The artwork is crisp, and the movement is fluid. There are no loading screens (besides the first), no flashing notifications, nothing to remind you you’re not in a real place. The sound design is the perfect complement, easing you into a relaxed pace with the steady patter of rain, then snapping you to attention with a well-timed thunder crash or creaking floorboard (if the ambient sound is too quiet for your taste, you’re free to sample Sam’s mixtapes). Walking around the house was spooky, but only because dark, empty houses are always spooky. I hurried through the basement with the same urgency that drives me out of my own basement late at night, even though nothing was chasing me, even though it was just an imaginary basement. I’m not sure that “this game made me feel like I was actually in a basement” is the best endorsement I could give, but I admire anything that can push my brain’s buttons so easily.

The twenty dollar price tag may sound like a bit much to ask for a self-described “interactive exploration simulator,” but if immersive storytelling is your jam, I think the cost of entry is fair. The quality alone is worth it, but you’re also supporting a team with the courage to tackle themes rarely addressed in games (I can’t get less vague than that, as I don’t want to spoil the story, but trust me, it is very much in The Mary Sue’s wheelhouse). Set aside an evening, make a snack, put on some headphones, and treat yourself to something good. There hasn’t been a game like this before, but I am sure it is the first of wonderful things to come.

Gone Home is available for Windows, Mac, and Linux. It can be purchased through Steam or its official website.

Becky Chambers is a freelance writer and a full-time geek. Like most internet people, she has a website. She can also always be found on Twitter.

Are you following The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]