Google Searches Show Where Racism May Hurt Obama’s Presidential Campaign

Having a black or female (or black female) president is a pretty established trope in the world of near-future fiction. That said, having elected a black president doesn’t mean we’re living in an episode of 24 and it doesn’t mean that racism is over. Historically, pollsters have tried to gauge the effect of racism in political campaigns through, what else, the use of polls. Now, a new study uses Google to try and tease out a greater level of accuracy polls could never achieve.

The problem with polling to try and detect accurate levels of racism is that you rely on those being polled to admit to their own racism. This is problematic in two ways. First, you’re going to miss self-acknowledged racists who aren’t comfortable admitting their views to a stranger as part of a poll. Second, you’re going to miss out on anyone who denies their own racist tendencies, but has them nonetheless. This is where Google comes in.

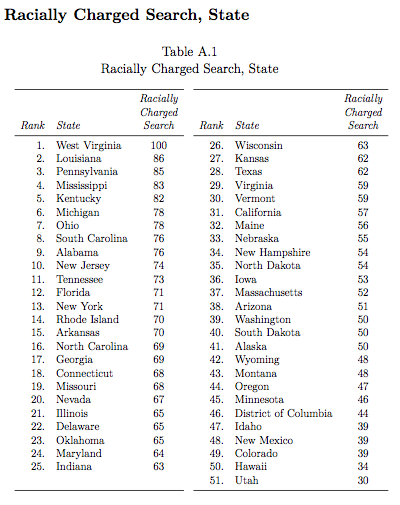

In a paper called The Effects of Racial Animus on a Black Presidential Candidate: Using Google Search Data to Find What Surveys Miss, Seth Stephens-Davidowitz of Harvard University breaks down the number of racially charged Google search terms by state in attempts to get a feel for the racist sentiments in a given area. Using searches from between 2004-2007 to try and gauge cause-and-effect instead of mere correlation, Stephens-Davidowitz put together the following list of states by how racially charged their searches are.

As for how Stephens-Davidowitz came into these numbers, here’s how he put it in the article itself. Heads up, racial epithets incoming.

The baseline proxy that I use is the percentage of an area’s total Google searches from 2004-2007 that included the word “nigger” or “niggers.” I choose the most salient word to constrain data-mining. I do not include data after 2007 to avoid capturing reverse causation, with dislike for Obama causing individuals to use racially charged language on Google. My regression analysis includes 196 of 210 media markets, encompassing more than 99 percent of American voters.The epithet is a common term used on Google. During the period 2004-2007, there were roughly the same number of Google searches that included the word “nigger(s)” as there were Google searches that included words and phrases such as “migraine(s),” “economist,” “sweater,” “Daily Show,” and “Lakers.” (Google data are case-insensitive.) The most common searches including the epithet (such as “nigger jokes” and “I hate niggers”) return websites with derogatory material about African-Americans. The top hits for the top racially charged searches are nearly all textbook examples of antilocution, a majority group’s sharing stereotype-based jokes using coarse language outside a minority group’s presence.

…

The estimated effect is somewhat larger when adding controls for an area’s Google search volume for other terms that are moderately correlated with search volume for “nigger” but are not evidence for racial animus. In particular, I control for searches including other terms for African-Americans (“African American” and “nigga,” the alternate spelling used in nearly all rap songs that include the word) and profane language.

The results imply that, relative to the most racially tolerant areas in the United States, prejudice cost Obama between 3.1 percentage points and 5.0 percentage points of the national popular vote. This implies racial animus gave Obama’s opponent roughly the equivalent of a home-state advantage country-wide.

It’s a pretty staggering impact but, as it’s worth noting that, as The Atlantic points out, popular vote isn’t the only thing that matters in a presidential election; the Electoral College is specifically designed to filter the popular vote. Still, these levels of racism could, and may, have a material effect on the 2012 election.

Aside from drudging up hard data on the racists attitudes of American citizens — or at least highlight American citizens’ likelihood to type racial epithets into a search engine — this study shows how Google doesn’t just direct us to webpages, but is also building a valuable database of social mores. By its very nature, Google is essentially an anonymous poll that compels us to use it, and be honest, in order get through our day-to-day lives. It’s not always the search engine that’s doing the searching.

(via The Atlantic)

- A look at the year 2011 in Google searches

- Google books tracks the life and death of words

- MillionShort search terms probably wouldn’t be very helpful

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]