I own far more books than will fit on our single bookshelf, which means I keep about half of them organized in the same cardboard box I put them in when we moved to our apartment. To that end, it kind of annoys my wife Raychel when I buy a new book rather than getting it out of the library. My protest is always that I might want to reread it, and anyway, she bought all those smoke alarms and we haven’t had a single fire. (That’s actually Homer Simpson, I’m being informed.)

There are some books, however, that Raychel doesn’t have to worry about me keeping in a box and creating more clutter because, much like the movies in this stellar AV Club listicle, once was almost more than enough. Here are six books I’d recommend to just about anybody, but afterward I’d also recommend a good cry, a funny movie and/or hugging a really fluffy dog.

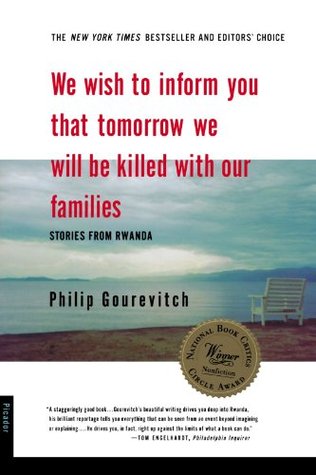

We Wish To Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families – Philip Gourevitch

Like its title, this 1998 non-fiction chronicle of the 1994 Rwandan genocide is heartbreaking in both its horrifying subject matter and the clinical, objective lens through which it views it. New Yorker contributor Gourevitch writes in a chronological zigzag, beginning with the aftermath of the murder of nearly a million Tutsis, and then traces the slow burn of the genocide all the way back to the country’s Belgian colonial period, when the Belgian favoritism toward the Tutsis for their “whiter” features set the ball rolling on decades of interethnic tension.

Gourevitch doesn’t spend much time on descriptions of the actual atrocities, but that’s little emotional respite, as the human faces he gives them—like a pastor who sold out the Tutsis in his flock, telling them it was God’s will, or Paul Rusesebagina, the heroic Hutu hotelier who inspired Hotel Rwanda—are just as much of a gut-punch.

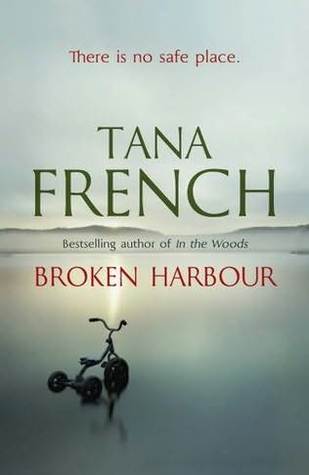

Broken Harbour – Tana French

All of French’s novels focus on detectives in Dublin’s Murder Squad, but with each new book, she shifts the protagonist/narrator, as well as the aspect of Irish culture she addresses. In the case of 2012’s Broken Harbour, that’s the havoc Ireland’s 2011 economic crash wrought on its burgeoning middle class. French’s protagonist, Det. Mick “Scorcher” Kennedy, is a man who strongly believes that bad things generally happen to bad people.

He and his partner are shaken up by the discovery of a dead father and children and a mother clinging to life in the titular half-built suburb, but find themselves in an even darker place as they investigate, piecing together a picture of a seemingly perfect family coming apart at the seams due to unemployment and paranoia. Like True Detective, French’s work hints at something supernatural or otherworldly dancing in the margins, but the true conflict is always driven by something all too earthly, and never is it more on display than in Broken Harbour.

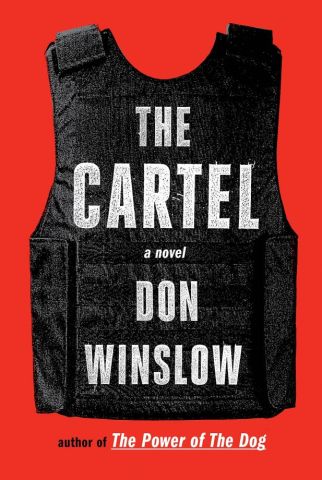

The Cartel – Don Winslow

The Cartel was released in June and almost immediately got some free publicity when notorious drug lord Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman escaped from a Mexican prison a few weeks later, just like the book’s antagonist, Adan Barrera, based directly on Guzman, does in the opening act. Although the novel’s antecedent, 2005’s The Power of the Dog, is itself excellent, this one zeroes in on the human toll of the drug war (both between the cartels and the DEA and among the cartels) in Mexico.

The atrocities Winslow describes, particularly those of the Zetas, a cartel composed of ex-Mexican military and police, seem too extreme to be real, but nearly all the worst of it really happened. Making the whole thing emotionally bearable, though, many of the most inspiring parts of the book, like the 19-year-old girl who became her town’s police chief after all the men fled in fear, really happened as well.

Mystic River – Dennis Lehane

Three friends, Sean, Dave and Jimmy, write their names in wet cement on a Boston sidewalk in 1975, only to be interrupted by a cop. It’s only after he’s put Dave in the back of the car and driven away that Dave realizes he’s not actually a cop. Three decades later, Dave is a deeply traumatized blue-collar worker, Sean is a divorced state police detective and Jimmy is a minor-league Al Capone to the neighborhood. When Jimmy’s daughter is found murdered, all three men crash back into one another’s lives, laying bare that day’s trauma, which the three men have dealt with about as well as you would expect of three stoic Irish Catholic family men. Lehane, one of the greatest genre writers working today, transcends that genre, wringing an American tragedy out of the expectations of “acting like a man.”

The Bluest Eye – Toni Morrison

In December 2013, the Village Voice interviewed Jim DeRogatis, the journalist who originally reported on the sexual abuse allegations against R. Kelly about how little negative impact they had had on the singer’s public image. “The saddest fact I’ve learned is nobody matters less to our society than young black women. Nobody,” DeRogatis said. This heartbreaking conclusion is on full display in Morrison’s first novel, chronicling the unrelenting misery heaped on Pecola Breedlove, a young Ohio girl dealing with unstable, alcoholic parents, the abuse of the world at large and a deep sense of internalized racial self-loathing (her fondest wish is for the eyes of the title). Morrison’s prose is as rich and beautiful as ever but I can honestly admit I likely wouldn’t have been able to finish this one if it hadn’t been assigned to me in high school.

Missoula – Jon Krakauer

Krakauer, famous for Into the Wild and Into Thin Air, initially intended to publish this jarring chronicle of how the University of Montana fails and undermines students who are the victims of sexual assault in early 2016. However, as Rolling Stone’s botched story on sexual assault at the University of Virginia fell apart, Krakauer, worried the public’s takeaway would be that campus rape isn’t a serious problem, moved the publication schedule up.

Krakauer covers several different cases, with some names changed and others not, anchoring the book with the case of Beau Donaldson, a star on the university’s Grizzlies football team convicted of raping a childhood friend in 2012. As horrifying as the crimes themselves are, Krakauer’s harshest indictment is of the vaguely cultish small-town atmosphere where all this happens, an environment where a young woman’s safety is secondary to a football team’s place in its conference. Krakauer succeeds where Rolling Stone failed by seeking out and talking to the accused as well, but it doesn’t create a sense of false balance at all; rather, reading their defenses gives us a front-row view of the “banality of evil” Hannah Arendt talked about.

(featured image via Ulisse Albiati)

Zack Budryk is a Washington, D.C-based journalist who writes about healthcare, feminism, autism and pop culture. His work has appeared in Quail Bell Magazine, Ravishly, Jezebel, Inside Higher Ed and Style Weekly and he recently completed a novel, but don’t hold that against him. He lives in Alexandria, Virginia with his wife, Raychel, who pretends out of sheer modesty that she was not the model for Ygritte, and two cats. If you don’t think Molly Solverson from “Fargo” is the best he will fight you. He blogs at autisticbobsaginowski.tumblr.com and tweets as ZackBudryk, appropriately enough.

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Published: Sep 4, 2015 03:28 pm