The way some people’s parents “were there,” at Woodstock or the ’68 Democratic Convention, I feel I was “there” for Harry Potter. I stood on line for all eight movies, the midnight showings, witch hat and novelty wand in tow; ditto the last several books, which my family always bought multiple copies of. Well into high school, when some compulsion towards ‘coolness,’ might have slapped an expiration date on a gal’s enthusiasm for fictional kingdoms, my friends were writing fanfic about the Weasley twins. We were not satisfied when J.K. Rowling concluded her series, and took it upon ourselves to bring the delights of the wizarding world into our real one as best we could. Once, a set of us high school juniors even locked ourselves in a basement and “sorted” everyone else in our class, deliberating over our peers’ personality traits as rigorously as we didn’t deliberate over our (non-magical) history homework. Even now, nearing thirty, I’m the girl whose first social wrangling impulse—trumping chit-chat, ‘Flip Cup,’ or ‘Charades’—is always “So, what’s everybody’s Hogwarts house?”

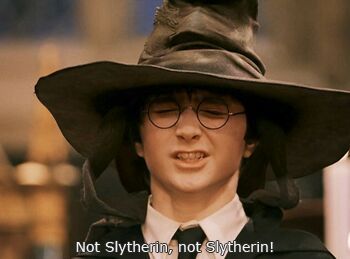

I mean, throw a rock in Brooklyn and you’ll hit some other nerd girl in a Ravenclaw scarf, proudly wearing her Deathly Hallows tattoo and offering up horcrux theory out of seemingly nowhere. But into adulthood, some of what remains most magical to me about the Harry Potter books is Rowling’s ability to trick a generation into conflating magical powers with what is essentially a personality quiz. Who you might be at Hogwarts remains as dire a litmus test as any I’ve met; for whatever reason, the Sorting Hat commands a fearsome authority over one’s inner life, in both this world and the wizarding one. Unfortunately, the four houses of Hogwarts paint a pretty facile picture of humanity. Everyone knows the breaks: brave kids are Gryffindor, chummy less-thans go to Hufflepuff, socially inert brainiacs to Ravenclaw, and—of course—diabolical, pre-serial killers go to Slytherin.

When J.K Rowling created the Pottermore website, she gave important encouragement to a fanbase that was already bent on inserting itself into the universe that seemed to exist in tantalizing parallel to our realer, duller one. For in important ways that make the Potter books different from the chronicles Prydain or Narnia, Hogwarts feels like it could be happening adjacent to this life; who among us waited for The Letter when we turned eleven? Who among us has a kooky neighbor and thinks, “squib,” when their back is turned.

When she invited us to sort ourselves, and when the internet followed suit with its many bastard quiz replicas—well, this meant something. For me, it was almost like Hogwarts, the magical, perfect “there,” had come to life all over again. It was almost like my favorite fiction believed in me right back.

I remember where I was when I first took The Quiz: on a family vacation, idling around a porch full of my relatives. People were guessing their houses and, in the process, confirming hunches about their magical alter-egos back to themselves. Math-minded sister Jamie was a Ravenclaw. Bold brother Ben was a Gryff. I assumed I’d also go the way of Luna Lovegood of Ravenclaw, whose accessories and bookishness I admired, but was also prepared to be pleasantly surprised by a Gryffindor placement. I would have even been okay with Hufflepuff, I think now. My friends had always joked that those goofs would have had the best parties, and the Puffs seemed to spend the least amount of time in their formative years fighting to the death with racists.*

Still, a part of me must have feared the worst. I took the quiz gravely, hemming and hawing over questions with oblique aspects (“The moon, or the stars?”, “Pick a potion!”) and attempting honesty re: the moral heavyweights (“Would you rather be liked, or trusted?”), perhaps figuring that a Gryffindor would be unflinching about her self-interrogation, but a Ravenclaw would be thoughtful. In an echo of the alchemy that only N. Flammel understood so well, a strange thing began to happen as I answered those questions. I realized that The Quiz had become about much more than the books I’d loved as a child, those which had shaped my imagination into adolescence. This Quiz, this doofy-ass Pottermore Sorting Hat Quiz, was going to tell me who I’d become as an adult. What of that formative magic had lingered in me?

For all I didn’t know in high school, some things were more obvious then. I was, then as now: dreamy, prone to wordiness, and loyal only to a small set of other malcontents. I already knew when I was seventeen that I’d never be the girl to lead the fight against bullies (systemic or singular), the way I knew I’d never be confident around boys, or good at sports, or enjoy yelling at someone outside of a theatrical context. It was easier then to make a self out of such borders. And maybe the reason so many of us are attracted to The Quiz (or the Hat, initially) is because it reminds us of those days when a short list of characteristics could nestle you into a group, that safe, familiar nook where you were seen and known.

You’ll have guessed, by now, the grim results of my porch experiment. Reader, I was shocked, and I really do mean shocked, when the mystical forces at Pottermore informed me that, contrary to my own envisioning of myself, I was, in fact, destined to enter adulthood as a Slytherin. I was so upset by this news that I actually cried a little, and then I made a new email address so as to re-sign up for Pottermore and take The Quiz again. Many of the questions were different the second time, and I did get Ravenclaw—but my family joked that making a new email address so as to corrupt results I didn’t agree with sounded like a pretty Slytherin thing to do. I became more distraught. Suddenly, on that porch, I was the most unmagical thing: a woman whose ability to self perceive was apparently as underdeveloped as Professor Trelawney’s, or Lockhart’s. I was, it seemed, a stranger to myself.

What are you supposed to do when your books read you? To go on feeling as “seen” by the Harry Potter books as I’d been, to continue kowtowing to the authority of Rowling’s imagination, I was being asked to reconcile my own vision of Me-ness (total ‘Claw) with what the world (or … some world) sees. As they grokked the extent of my distress, my family turned palliative. Think of Merlin, someone said. Or Severus Snape! The bravest (yet most obsessive, most ill-humored) man in all of kid fiction! Lin-Manuel Miranda claims to be a proud Slytherin! So does Taylor Swift! (My wails got louder…) And aren’t the books biased against Slyther-kids anyways, being written chiefly around the Gryffindor common room? Not everyone in those green and black robes must have been pure evil. How could that be a thing in a children’s book? And then, as they grew weary of my screams: It’s only a quiz, Brittany. What went unsaid? It’s only a franchise, a neighborhood at Universal studios. It’s only a play. It’s only everywhere, forever. It’s only your childhood.

The only balm that did any kind of good was my mother’s reminder that the “real” Sorting Hat will control for choice. If I really feel myself to be un-Slytherin, as the boy who lived did, no one is gonna make me sit with Pansy Parkinson. Yet, there was something to the authority of Pottermore, wasn’t there? Rowling herself had made it! As my tears dried, I let myself engage in the first of a hundred subsequent thought experiments: So, what if I am?

… If I were an English wizard, inhabiting a very particular fictional universe that is almost certainly not real, what if I were sorted into the bad house? What would it say about me? What would it mean? After I received my results, I knew immediately why I’d gotten Slytherin. The Quiz, in its algorithmic wisdom, had parsed the qualities I dislike the most about myself: an ambition that isn’t always tethered to goodness. A need to be liked which apparently trumps my desire to be trusted. I had said the moon and not the stars, I had picked the silvery potion. When I really got to thinking about it, there was an angle from which these responses coalesced into a personality that wasn’t bound by its bravery, intellect, or loyalty—but a mad drive toward self-governance.

Later on this same vacation, I remember asking my mother what she thought I’d been like as a small child, and whether this tracked with the woman I’d become. Her answer surprised me” “I thought I knew who you were for a long time, but when you were a teenager you went this whole other way,” she said. “You used to be so bossy!” I read in this remark a comment on the way I’d transformed, at some point, from a confident girl into a neurotic lady. Puberty had done a number on my self-esteem. What my mother didn’t mention was how I’d chosen to repurpose the perceived excesses of my personality, alchemizing vibrance into cunning, becoming resourceful in order to empower my creativity. Perhaps, then, it was gendered and connected to race, I told myself. Maybe the world had made me a Slytherin, with its unfairness, its special taxes on the characteristics that rendered me “Other.”

“But see,” someone else would tell me (later, at a party, as I explain my theory:) “That really sounds like self-preservation logic to me. Pretty Slyth.”

This party guest is sort of pulling my leg, but I am not here for it and so prepare my usual protest. “I have so many books. I was Most Creative in the 8th Grade. I’m a gosh-darn artist with crafty paper-chains all over her living room. I am a motherfucking Ravenclaw, okay?!”

“Sure, sure,” they say, eyes darting toward the other side of the room. “I mean, it’s whatever. I liked the books and everything too, but um … now we’re adults. Remember?”

And there’s the rub. Harry and the gang, spurred by trauma and the apparent lack of higher education opportunities in the wizarding world, were only children. We never got to see them grow into adults, where their personalities might have flexed and shifted,** where the room may have moved underneath them, not to mention the stars (and moon!) above them. I remain consoled by the fact that I may (and mostly do) identify as a Ravenclaw—you can choose to be anything, in a fictional world—but the nice thing about being real, and an adult, is the ability to live on nuance. Navigating muddle has made me resourceful and cunning. Caring deeply about what I love has made me ambitious. Imbibing art has made me question the world around me. Witnessing injustice has made me braver. These qualities don’t amount to a list of traits, or a pair of colors on a flag.

Perhaps as we age, we all cross the borders that once seemed impossible. We empathize with former enemies, or compomise where we wouldn’t have before. Consider how Ron is disloyal in book seven, or the hundred ways that Harry’s a the worst in five and six. Had the Hat sorted them at those moments, would its analysis still have been ‘right?’ Or, is it possible that the gift of containing multitudes is what makes our real world ever so slightly, every so often, superior to a kingdom where people get ‘sorted’ at all?

In any case, I’m still grappling with my Slytherin qualities, but in certain recent moments, when I’ve loved myself—and this realer, duller world—the best, you should know I was listening to Hamilton. (And once, Taylor Swift.) I was dancing around in a big, goofy, surprising circle, with the people who love and know me even better than my books do, feeling myself, which is to say: a number of things at once.

*Except, of course, poor Cedric Diggory.

**I’m an anti-epilogist.

(featured image: JKR/Pottermore, Warner Bros.)

BRITTANY K. ALLEN is a New York-based writer, performer, and library goblin. Her essays and fiction have been previously published or are forthcoming in Longreads, Catapult, The Toast, and elsewhere. Her work has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize, and she was a 2017 Van Lier fellow at the Lark Play Development Center. Brittany’s also received recent art support from SPACE on Ryder Farm, the Sewanee Writers Conference, and Ensemble Studio Theatre, where she’s a member of Youngblood, the Obie-award winning playwrights group. As of this May, she’s also a member of the Emerging Writers Group at the Public Theater.

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Published: May 23, 2018 03:37 pm