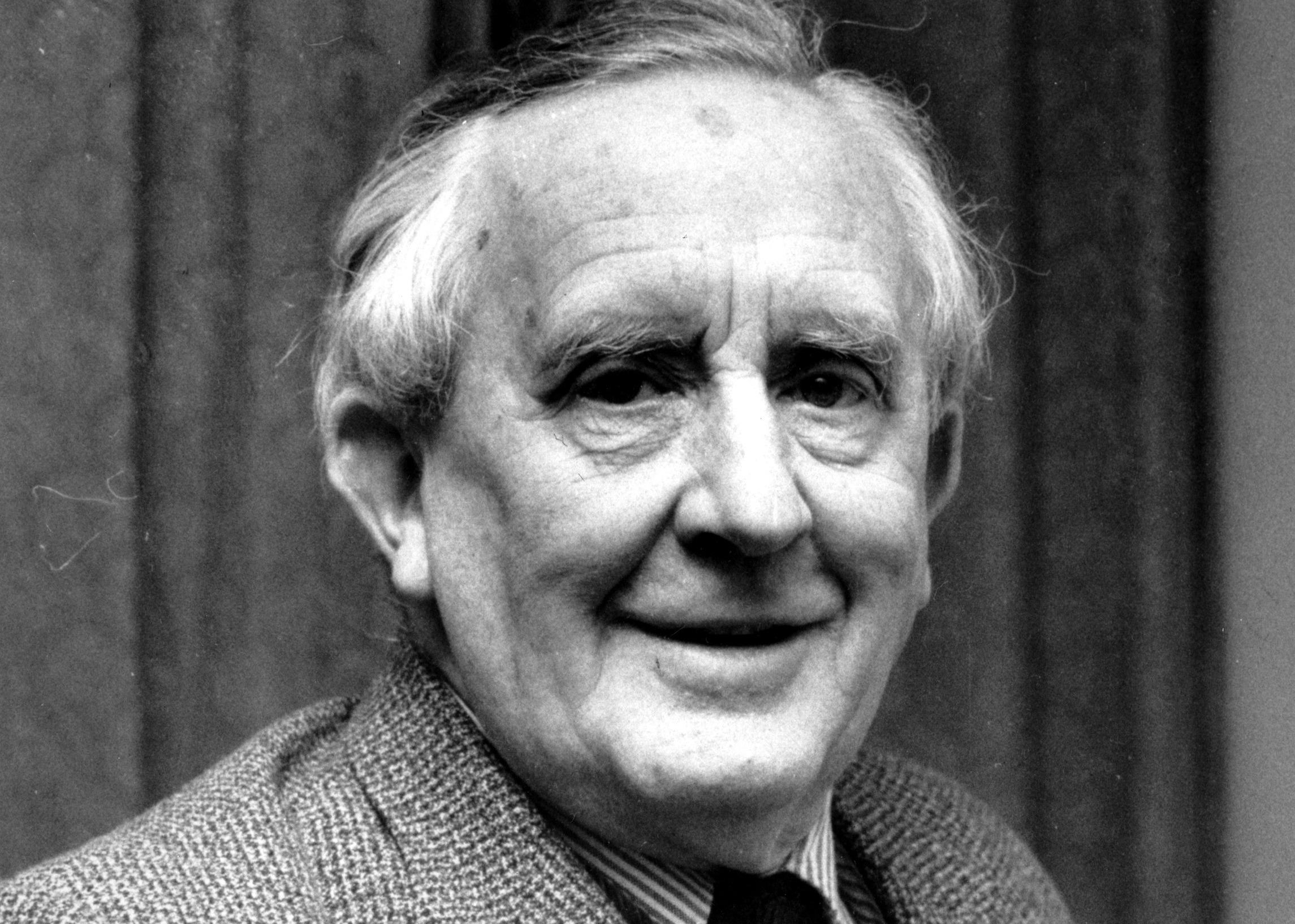

How Tolkien’s Real-Life Experiences Inspired His Creation of Middle Earth

Catch me Tolkien up at my local library! ...No? Nothing?

There’s been some mixed feelings about Amazon’s new Lord of the Rings series, The Rings of Power. People are rightfully dubious of anything Amazon puts out in the world, what with all the, you know, Bezos. But for those who are curious, have I got a treat for you!

As someone who studied History in undergrad, AND someone who’s a massive nerd, I’ve always found it incredibly enjoyable to take a dive through the history of Middle Earth, both conceptually and literally. There was so much that went into this universe, due in part to Tolkien’s own talent in world-building and the influences of world events at the time. At once, Middle Earth is the progenitor of modern fantasy as we know it, and it’s a reflection of its time (not always in the best ways, mind).

With all that being said, let’s dive right in.

Origins: Of Books, War, and Love

Everything ultimately stems from Tolkien’s zeal for literature, in all forms. He was an avid scholar throughout his life, the foremost manifestation of which came about while studying at Oxford. The young Tolkien was already creating worlds in his head, lost in fantasy, writing new languages and painting images of his world instead of writing papers.

That said, he did graduate with first-class honors, as he was able to aptly balance his personal interests with his interest in his field of study. His interests ranged from classics, to traditional literature, to linguistics, and especially to the mythologies of other cultures. Unfortunately for this young man of exceptional imagination, Britain would enter the First World War in 1914, and although he was able to avoid the initial drafts due to his studies, he was pressured, like so many men of his age, into joining up by the time he’d completed his finals.

Tolkien was no great advocate for war in the first place, but the experience proved more than horrific for him. Whilst he came down with trench fever, many of his old mates from school were killed, and he found himself spending his remaining years in service either on medical leave or attending to garrisons. Writing was one of his only sources of solace, expanding upon things the war impressed upon him, including the demolishing of social barriers and class divides. But his other source of solace was his dear wife, Edith, who visited him once and danced in a hemlock grove for him—a memory that was so impactful, it helped to inspire a core part of The Silmarillion:

I never called Edith Luthien—but she was the source of the story that in time became the chief part of the Silmarillion. It was first conceived in a small woodland glade filled with hemlocks at Roos in Yorkshire (where I was for a brief time in command of an outpost of the Humber Garrison in 1917, and she was able to live with me for a while). In those days her hair was raven, her skin clear, her eyes brighter than you have seen them, and she could sing—and dance. But the story has gone crooked, & I am left, and I cannot plead before the inexorable Mandos.

Letter #340, penned by Tolkien

Ultimately, it’s no surprise that most of his lore didn’t get firmly established until he was released from his military duties in 1920. Tolkien began to take up positions in universities, as a reader (i.e. a recognized academic in pursuit of research) and tutor. In regards to the former, he spent much of his time translating old texts, most notably Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and the ages-old Beowulf.

All of these experiences, from the lowest lows to the highest highs, contributed to the creation of Middle Earth. It was during his tenure at Pembroke College, that he finally set about to writing the lore, in the form of the completed Hobbit, and the very beginnings of what would eventually become the complete Lord of the Rings.

Other Influences, Internal and External

In researching who Tolkien was as a fully-faceted human being, I can say with some certainty that he was a bit of a sponge, yet a self-possessed sponge. He was a sensitive man who absorbed much in the world he lived in, yet had the smarts and critical-thinking skills to determine his own opinions from what he bore witness to. These opinions would definitively influence the creation and development of Middle Earth.

For instance (and notably so), Tolkien was a devout Christian for pretty much his entire life, and it’s not a stretch to consider Middle Earth a world with Christian sensibilities. There is a definite sense of good vs. evil in Tolkien’s world, amongst other things, which he elaborates on in a letter to his friend, the Jesuit priest Robert Murray:

The Lord of the Rings is of course a fundamentally religious and Catholic work; unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision. That is why I have not put in, or have cut out, practically all references to anything like ‘religion’, to cults or practices, in the imaginary world. For the religious element is absorbed into the story and the symbolism.

Letter #142, as written by Tolkien to Murray

That being said, scholars are quick to point out that Middle Earth is also rife with references to paganism and polytheism, which shows that Tolkien was, at the very least, a dedicated and well-rounded scholar to the last.

Or perhaps, much of this had to do with Tolkien’s affinity for nature, influenced by his childhood and such instances in the wild as he’d had with Edith in the hemlock grove. The elves, for instance, are highly attuned to nature as part of their very being, and while conservationism wasn’t a large political stance at the time, Tolkien was always a staunch advocate for the preservation of beautiful things.

Perhaps the most controversial point of origin for Middle Earth, however, is its racial (or, rather, racist) undertones. As a historian, I was taught not to view things anachronistically—or rather, through a strictly modern lens—and to instead consider the context of the time. With that said, it’s imperative to note that Tolkien wrote and established Middle Earth during a time of xenophobic, wartime anxiety (the books were written between 1937 and 1949, but he primarily worked on them during WWII). The phrase “Yellow Peril” comes up quite a bit when discussing Tolkien’s forays into racial descriptions, and I believe them to be apt for what they are trying to describe. For all intents and purposes, Orcs are East Asian in characteristic and stereotyped nature; they lack a Christian sense of morality and embody the wartime propaganda of “West Good, East Bad.” Conversely, elves are almost ubermensch-ish, with their physical qualities and their untouchable nature—a likely influence from his irritation that anti-Nazism tended to blend with anti-German attitudes in totality.

Now seems like a good time to very quickly add that Tolkien considered himself to be anti-racist, and he very well may have been for the time period. As well as this, he strongly argued against Nazi race theories and was anti-war to the umpteenth degree, especially in regard to Nazis. HOWEVER, he also had a fondness for German culture and mythos, hence his adamant stance that Germans at the time did not automatically equate to Nazis. By modern standards, of course, we would view such back-and-forth attitudes as unsatisfactory (dare I say, problematic even), but in a historical context, it’s important to understand where a person might be coming from all the same, lest we color their entire ethos by our own unknowing standards.

In any case, Tolkien most likely acted with ignorance as to how these racial depictions would be interpreted, which is a shame, but demonstrates that even the most talented writers can err.

To Conclude

While he faulted from time to time, ultimately, J.R.R. Tolkien was a brilliant man, who lived a rich, if at times painful, life, and it was the sum of such a life that brought us Middle Earth. Of course, there is much more that could be expanded upon the points I raised, but I assume that if you’re here, you were mostly looking for a quick read to give some context as to what piece of Tolkien media you were watching.

If, however, you would like to learn more about these origins, as cliche as it sounds, your best bet is your local library or various online databases. There are no shortages of Tolkien scholars, and I find that it’s rather intriguing to compare the source material to what scholars have found.

…That said, I can’t, in good faith, recommend the Tolkien movie from 2019. Sorry, Nicholas Hoult.

Please feel free to add to the discussion in the comments below, and in any case, happy reading to you!

(Featured Image: AP)

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]