(Spoilers for When Marnie Was There)

When I was younger, I wanted to know if, given the choice, my family would have chosen to have me in their lives. What am I in the story of your life? A sequel? A spin-off? Irrelevant?

These questions are inherently unlikeable. They’re needy, insecure, and cloying. They expose a deep-seated fear of abandonment that people don’t know how to respond to. That’s exactly why I was so moved to find that these questions were at the heart of the most recent Studio Ghibli film, When Marnie Was There. It’s a brave choice precisely because it’s an uncomfortable one.

The progression of female protagonists in film seems to have moved slowly through multiple stages, from the existence of a woman in a central role, to a woman whose role isn’t purely to be saved by the man, followed by the boom of the Strong Female Protagonist, and more recently the development of complicated—potentially unlikable—women characters. So much of the hype surrounding Gone Girl was merely reverberations over the shock that it deigned to feature a sociopath who was a woman. Similarly, last year’s critically acclaimed, female-centered horror film The Babadook was considered one of the most frightening films of the year. There were many valid reasons for this, but I would argue the very idea that the underdog single-mother who genuinely loved her son could simultaneously hate his very existence was more terrifying than any demon, ghost or serial murderer. When Marnie Was There is Studio Ghibli’s foray into developing an unlikeable female protagonist, and it’s important, if only to dilute the shock over the realization that a heroine can be compelling without being typical.

Anna, the protagonist of Marnie, is an orphan living with foster parents. When the audience first meets her, she is unhappy, self-conscious, and antisocial, and we don’t understand why aside from the assumption that she is a stereotypically angsty pre-teen. By choosing to conceal Anna’s history until the final act of the film, we very realistically progress through most of the story by judging Anna as we would judge anyone who we don’t understand but whose actions are unappealing. Anna is ungracious towards the adults who are kind to her, unresponsive to offers of friendship, and sometimes, unjustifiably mean. Regardless of the circumstances of her life, it’s understood from the very beginning that Anna, herself, is a major cause of the loneliness she experiences, and Anna knows this, too, as one of her first lines is the classic, “I hate myself.”

According to film media, childhood is a time for happiness, tenacity, hope and perseverance, but there is no room for sadness. You never see Cinderella mourn for her parents on screen, Simba’s grief after the death of his father in The Lion King is immediately replaced by a montage of his carefree life in the jungle, and Frozen conveniently time-lapses over Elsa and Anna recovering from the death of their parents. This year’s mental health-themed film Inside Out is only able to express the importance of sadness by first overloading the film with joy. Literally. Marnie is the inverse; it’s first overloaded with sadness, then reluctantly learns to accept joy.

Stories and narratives are powerful because they paint our understanding of how we are meant to fit into the society around us. Anna’s worldview consists of an “inside” and an “outside”—some people fall within the scope of the overarching narrative, while others exist only on the peripheries. When Anna looks at the children around her, her peers are happy, lively, friendly, and occasionally spoiled but redeemable. Anna doesn’t fit in, just as the film itself doesn’t quite fit into the canon of children’s films; she needs to learn to grieve for the loss of her family, to forgive her own self-loathing, and to face her fear of abandonment. There is no narrative to guide her; she has to forge her own.

All stories have a beginning, and in most cases, it doesn’t begin with you. You are not your own person—not completely, anyway. Your life begins with those who came before you, perhaps your parents or grandparents, your culture, history, and heritage. The series of events that led to your existence. The legacy that you can choose whether or not to inherit.

Anna searches for the beginning of her own story by asking the same questions I used to ask as a child: Was I wanted? Did somebody choose me? What am I to you? Anna answers these questions by conjuring up her grandmother as a girl her own age—the eponymous Marnie. Whether it’s a stroke of magical realism or simply a child’s imagination, Anna wanders into the past and meets Marnie, whose identity is still a complete mystery but who seems strangely familiar. Marnie, however, immediately likes Anna, and she quickly becomes Anna’s first friend. This is made all the more poignant when it is later revealed that the elderly Marnie was indeed Anna’s first friend when she was only an infant.

Anna’s story reaches a moment of catharsis when, believing she had been abandoned by Marnie, she finally vocalizes the fear that has been plaguing her her entire life. She accuses Marnie of abandoning her, leaving her behind, and betraying her. The real wound Anna has ripped open is her unresolved grief resulting from the actual abandonment by her mother and, later, the death of her grandmother, Marnie. As a child, Anna mistakenly translated grief into abandonment and loneliness into unworthiness. It’s fascinating to see this psychology front and center in a children’s film, because it’s so human and so literal. There is no villain more horrifying than one’s own self-doubt.*

By conflating time and space, the film builds upon the fantasy that there is a timeless inevitability to human connection. Anna has always been in Marnie’s life—appearing like a time-traveler at major moment’s in Marnie’s childhood—and Marnie continues to exist in Anna’s life, though she has passed away in real time. Anna and Marnie are bonded not because they are blood relatives but because they love one another and have chosen each other as irreplaceable parts of their own lives. When Anna accuses her of abandonment, Marnie responds with the words that I think all of our deceased loved ones would have liked the opportunity to say: “I didn’t mean to leave you. Forgive me.”

When my grandmother died, I thought my life had ended, too.

She raised me during my most crucial years when my mom was working, my sister was a teenager, and my dad was dying of cancer. It was my grandmother who taught me the multiplication table and adapted fairy tales to include the things I liked. My grandmother’s back was ruined from carrying me, and she loved me enough to chastise me when I did things wrong. “Who was I,” I wondered, “to deserve such love?” I couldn’t accept the fact that such things could be unconditional; I was afraid of being abandoned.

After my dad died, my grandmother returned to China, where she knew the language and had a community. Her absence left a void in my life that I tried to fill by becoming the sequel that she deserved. I convinced myself that she had raised me to become someone she could be proud of, someone worthy of inheriting the rest of her life, and someone that she would choose to have continue her story. When she died, I felt as though this purpose died with her. What am I to do with myself now? For whom do I live?

It was easier for me to take issue with myself for suddenly losing focus in life than it was to grieve for a person I had lost. To me, grief felt like such a large thing—so grand that the world would not have space for it and the havoc it would cause. It’s messy and inconvenient, full of feelings of abandonment, insecurity, and the courage to admit that you have loved and been loved and still to have lost. To grieve is to admit that your life is not your own, that you exist in symbiosis with others, and that the feeling of losing someone is the same as a part of you dying. To grieve is to accept that you will be dying for the rest of your life.

Like Anna, I never learned to grieve as a child, but I’m learning now, slowly. I’m learning to be ugly and unpleasant, uncomfortable and awkward, to take the time and space that is mine to have, to be contradicting and horrifying, and to exist with sadness and happiness, individualism and legacy. In grief, I am trying to be the complex female protagonist I am deserved.

*Except perhaps a complex female character.

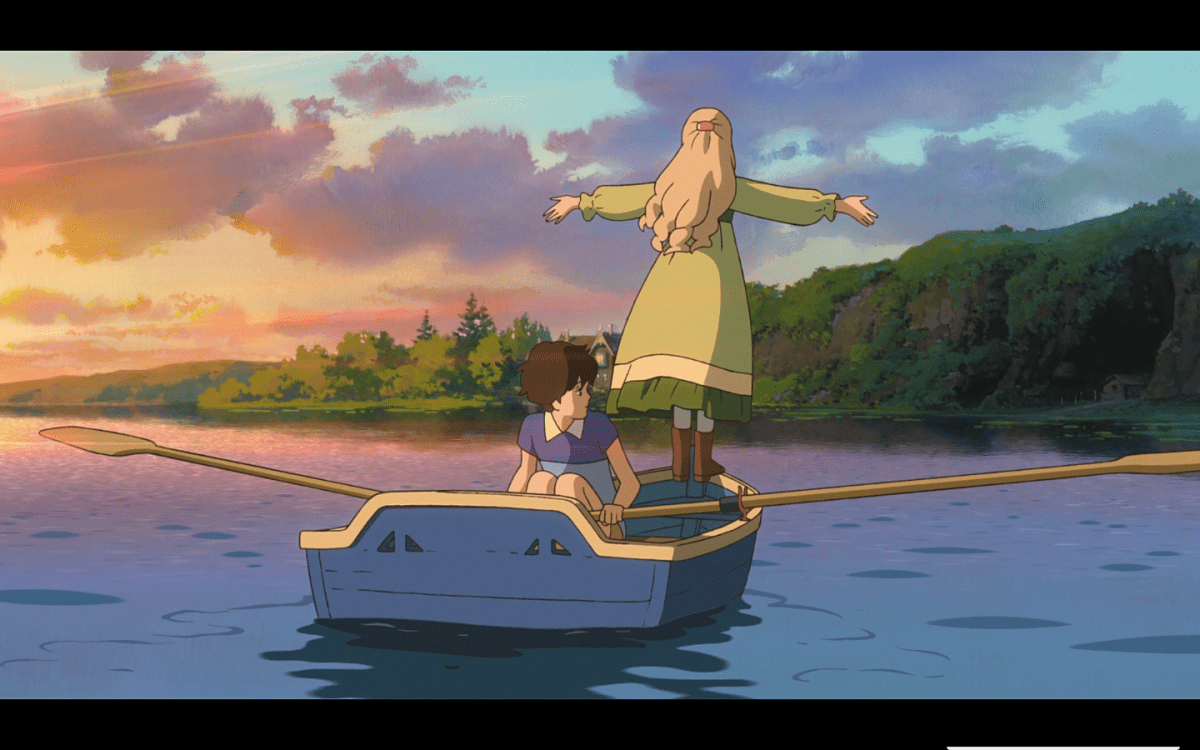

(image via Studio Ghibli)

Jasmine Wang likes to be pensive and then travel to a different country and do the same thing. To read more writing on mental health, vagabonding, the art of overthinking and an occasional bit of pop culture, follow her at www.plaintofu.com.

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Published: Nov 27, 2015 12:50 pm