In Defense of the Little Shop of Horrors Theatrical Cut

Yes, the sappy one. Hold on; I can explain.

In honor of the upcoming holidays—I’d intended Thanksgiving but maybe the self-serving bloodthirst of Black Friday is more thematically appropriate—I wanted to tip a hat to an old favorite. Alternately: I’m happy that Frank Oz’s intended version of Little Shop is out in the world, but it’s the version quickly making itself scarce that I’m grateful for.

Few words are as dirty as the phrase “focus testing,” the process in which bewildered strangers representing various marketing demographics are ushered into the screening of an unreleased film and then battered with questions about their feelings. Alright, it’s a bit more involved than that, but it’s also a process well known for being used as a crutch by nervous studio executives (also known as The Man) to rein in artistic types who want to try out something that, God forbid, might fail. The fallacy of this system has been discussed in broader scope by more learned souls than I, so today, let’s keep it simple. There is one case in which I remain in favor of the results of a focus group: the infamous edited ending of the 1986 film Little Shop of Horrors.

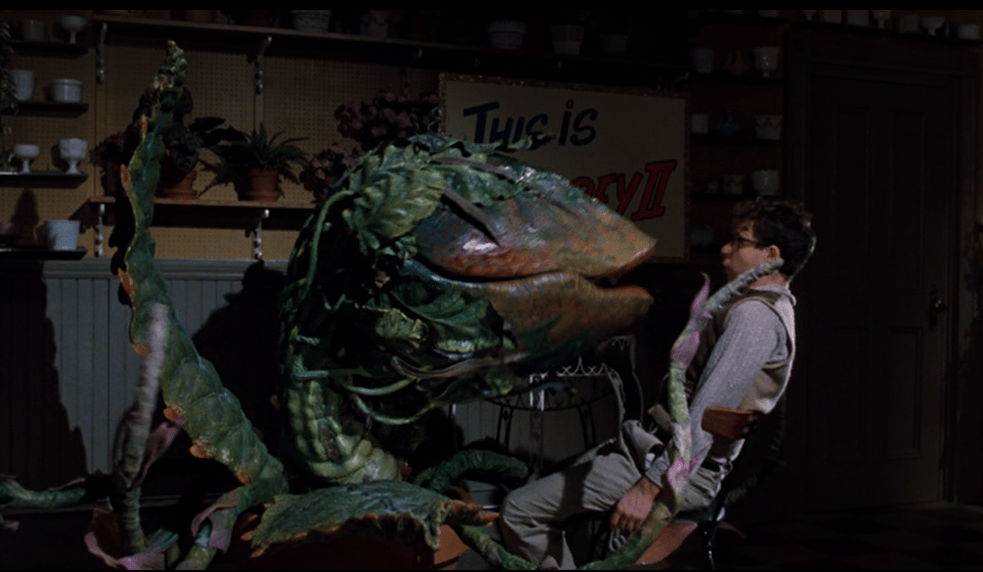

For those not in the know, a brief history: Little Shop of Horrors is, at its basest roots, the story of a poor young man, Seymour Krelborn, who finds a mysterious plant that brings him a great deal of wealth, accomplishment, and the love of the girl he was pining for. The trouble is that the plant feeds on blood, and as it gets bigger and the stakes get higher, Seymour has to resort to feeding it bodies. The story was originally a 1960 film born from the production house of gimmickry master Roger Corman, with the plant serving as a pretty heavy-handed drug metaphor and Seymour as the only victim. In 1982, the story was adapted into an Off-Broadway musical with a score furnished by future Disney Renaissance composer Alan Menken, becoming a Greek tragedy rather than a morality play (a stroke of genius that no doubt has a great deal to do with the play’s enduring quality). That musical then became the basis for the 1986 film starring Rick Moranis and directed by Frank “he did things besides Muppetry?” Oz.

Now, the play ends with Seymour, his paramour Audrey, and eventually the entire planet being consumed by the ravening alien plant dubbed “Audrey II.” Seymour’s undone by his fatal flaw, there’s a Greek chorus, and the show ends on a direct address to the audience called “Don’t Feed the Plants.” It’s a metaphor, y’see. The film was initially shot with that ending as well, until focus groups declared that they hated it, and Oz was forced to go back and shoot a happier ending with Seymour and Audrey surviving (as well as a small Audrey II peeking up out of the idyllic garden). People have hated that ending ever since, but while it’s definitely sappy, perhaps unduly so, it’s still a better fit for the finished film than the original ending.

The first issue is one of medium, which is almost unfair to hold against the film. “Don’t Feed the Plants” is directed toward an audience assumed to be in the same room and is almost always staged correspondingly (plant props falling on the audience or a giant puppet looming over the seats). It takes advantage of the intimacy of theatre as a medium in order to impress that last message as a plea by the dead characters, and that in-person bond with the actors is a huge part of making something like that work.

Oz tries, to his credit, making the final shot of the director’s cut involving Audrey II seeming to rip through the screen, but it’s simply not the same, and once the characters we’ve spent 90 minutes with are dead, there’s no urgency or horror in seeing unnamed civilians overwhelmed by vines, nor does it help that he cuts up the rhythm of the finale to twice its original length in order to have long, looooooong shots of giant plants rampaging through the city. Because it alters the stage convention of Seymour et al. returning as plant buds to sing the final number, it doesn’t so much surge into its ending as it limps the remaining six minutes until the credits finally roll. Even Seymour’s death lacks punch on screen. While his stage counterpart died making a final run at the plant with an axe, screen Seymour is picked up and swallowed up with agonizing, passive slowness.

“Passive” is the word du jour when it comes to film-Seymour. Rick Moranis’ performance is wonderfully sweet and endearing, and perhaps it’s because of that there are a dozen little cuts and tweaks centered around absolving his character of culpability. Stage-Seymour’s arc is one that takes small but active steps toward his own damnation, thus making it a tragic but fitting end when he sacrifices himself trying to end what he started. Film-Seymour might go through the same basic motions, but as film goers, we’re used to sympathizing with people who do bad things for sympathetic reasons, and the film almost goes out of its way to make the overall tone sympathetic: the film death of sadistic dentist Orin ends with Seymour saying that “it was for her,” and Orin’s first confused and then non-repentant reply hammers home that this is a man better off dead; likewise, by having Seymour successfully pull the gun, it cuts away the staged version of Orin pitifully begging Seymour (in song!) for help.

Mushnik’s death is also given a semi-karmic edge in the film. While stage-Mushnik is no saint, the script plays genuinely on the fact that he’s troubled by the implication of Seymour being a murderer (“just so my conscience can rest easy” is his last line before Audrey II starts up “Suppertime”). Film Mushnik, meanwhile, not only saw Seymour chop up Orin (rather than only suspecting it) but is perfectly fine with letting that fact slide in the name of blackmailing Seymour for the plant. And Seymour’s active hand is once again removed, having him babble in shock until Mushnik trips into the plant on his own (stage-Seymour manipulates Mushnik into crawling right into Audrey II’s mouth). In both cases, Seymour’s biggest sin is passivity, allowing bad things to happen for his own advancement but not actively taking part in them. Even “Feed Me” is restrained: one would think that the film would take advantage (as it does with other numbers like “Somewhere That’s Green”) on at least a cutaway or two when Seymour is indulging in his more selfish desires for fame. Instead, we stay in the room (which probably has something to do with that fantastic puppet), and Audrey II looms so large as to make Seymour seem like the helpless prop.

Much of this is helped along, in the stage show, by the three chorus girls (Chiffon, Crystal, and Ronette) who comment on the action of the play. Most of their numbers are cut or shortened to help with the film’s pacing, meaning that “You Never Know,” about Seymour becoming famous after his radio interview (and positively loaded with the toxic masculinity and capitalist success language that push him to his doom throughout the play), gets replaced with the functional but less subtext-heavy “Some Fun Now,” the reprise of the opening cautionary tale prior to the end of act I is gone, and most importantly, “The Meek Shall Inherit” omits Seymour’s monologue.

“The Meek Shall Inherit” is the montage number wherein Seymour is deluged by contracts, fame, and fortune. The meat of it can still be seen in the film, though you’ll notice that Seymour mostly sits, silent and bewildered, as he has for much of the film. The full song, by contrast, includes an interlude where Seymour argues with himself about signing the contracts, knowing that agreeing to it will mean killing more people to keep Audrey II alive. But, afraid that Audrey won’t love him without his success, he makes the decision to go through with the agreements—it’s his last chance to back out, and instead he signs his metaphorical death warrant. The fact that we see him work through and make that decision is crucial as a turning point. It’s what makes the line, “You’re a monster, and so am I,” work, and it means that without it, Seymour works only as a piteous and not a tragic figure.

In fact, the one active move film-Seymour makes in distinction from stage-Seymour is to take a stand after the arguably accidental murders, not only not making that damning decision about the contracts but instead vocally refusing to give Audrey II more human meat. He becomes a hero struggling to claw his way out of the pit he blundered into rather than a Shakespearean victim, and the needs of the third act correspondingly become different.

In particular, the film-only number “Bad” (no doubt written, as is common for film musicals, to have a shot at the Oscar’s Best Original Song category) only really works in a scenario where Seymour makes it out alive. It’s a grand eleven o’clock piece of gloating for Audrey II and a brutal, semi-slapstick gauntlet for Seymour as he tries to take the plant down. The effect of placing that sequence before Seymour’s death not only has a cruel effect on the tone (he’s not just eaten but humiliated first, and doesn’t even get that last active choice with the axe), but also results in Audrey II having two victory moments back to back—rather than the confrontation being focused on Seymour’s failing and then leading into the idea of The Plant as a bigger, more metaphorical threat to be presented to the audience.

But “Bad” does work as a final test that Seymour needs to go through to atone for what he’s done, accidentally or not. It works as the moment when he decides to overcome his sin of passivity and become an active hero. That feels, corny or no, like the story the film specifically is writing for its Seymour—not a tragic downfall, but a transition from innocence to experience (so yes, even that gotcha moment with the bud works, as it ties well into the idea that Seymour might have to face up to his old sins in future). It wound up telling a different story, one that arguably lacks the brutal emotional punch of the stage show but meshes better with the film’s high concentration of weird comedic bits. (Looking at you, Bill Murray!) The front half is so loaded with goofy guest stars and tongue-in-cheek humor, so dialed back in letting Seymour be an actively flawed character, that ironically, it’s the tragic end that winds up feeling like a cheat.

And besides, Rick Moranis and Ellen Greene are too damn cute for me to want anything but the best for them.

Want to share this on Tumblr? There’s a post for that!

Vrai is a queer author and pop culture blogger; they’re currently deep in a research hole with Herbert West’s name on it. You can read more essays and find out about their fiction at Fashionable Tinfoil Accessories, support their work via Patreon or PayPal, or remind them of the existence of Tweets.

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]