She’s been a veterinarian, a dentist, and a wildlife conservationist. She’s spent weekends rollerblading with her boyfriend Ken, shopping with friends, and wearing glamorous velvet and bedazzled gowns to formal events hosted on beige bedroom carpets. She drives a Corvette, a Jeep, and an RV. She owns several homes, nearly all of which have multiple floors (most come with an elevator). Her enviable list of collaborators includes Bob Mackie, McDonald’s, Caboodles, and Hello Kitty. She has Ava DuVernay’s number. She has been to space. In her 60 years of existence, there’s only one thing Barbie hasn’t been: Pregnant.

At least not to our knowledge. Her best friend, Midge—she of auburn hair, married to Ken’s “friend” Allan—got pregnant once, in 2002. (Given that she has three children, Midge was presumably knocked up more than once, but her first pregnancy occurred off-box.)

Margaret “Midge” Hadley was introduced in 1963, four years after Barbie made her big, blonde debut. She had the same hyper-unrealistic dimensions as Barbie so the two could share clothes, but her face was rounder and more cartoonish. With her auburn hair and voluminous freckled cheeks, the classic Midge bears a striking resemblance to Randy, the stink-faced puppet who bullied everyone on Pee-wee’s Playhouse. As M.G. Lord writes in Forever Barbie: The Unauthorized Biography of a Real Doll:

Her debut commercial was a catalogue of tortures endured by homely teenage girls. Midge, the ad alleged, “is thrilled with Barbie’s career as a teenage fashion model.” But anyone who has ever been sixteen and female knows she was probably rent with feelings of inferiority.

“Barbie has introduced Midge to her boyfriend,” the ad continues, “and the three of them go everywhere together.” Terrific. Tagging along after Mr. and Miss High School. If plastic dolls could kill themselves, I’m sure Midge would have tried.

Midge enjoyed many of the same activities and privileges as Barbie despite never achieving the same level of popularity—a characteristic that made Midge inherently more relatable. But relatability isn’t as attractive as being hot and perfect, something little girls who play with Barbie know intrinsically, even if they don’t fully understand what that means yet. After a few years in Barbie’s shadow, tagging along to the beach and going for rides in Ken’s sports plane (we used to be a proper society), Midge disappeared.

Midge returned 20 years later, in 1988, with new hair and a new face. With the exception of her signature freckles and bright red hair, Midge looked almost exactly like Barbie. They continued their careers as aesthetic tourists in vaguely named collections: California Dream (beach), Beat (pop stars), Disco (disco), and—my personal favorite—Cool Times. Released in 1989, the Cool Times line embodied the cultural transition into the ’90s with two accessories: activities and treats. Barbie had a scooter and ice cream, Midge came with a pogo stick and a bucket of popcorn, Teresa had a jump rope and a burger, Christie had one of those paddles with a bouncy ball and a hot dog, and then there was Pizza Ken. He had a kite with a pizza slice printed on it, a shirt with a pizza slice printed on it, and a comically large slice of plastic pizza. Even his suspenders were cool. I loved him. That was my guy.

When Midge came back, it wasn’t just her face that had changed. In 1991, Midge and Alan (Mattel took an L out of his name) got married, and for once, Barbie was relegated to supporting character—as Midge’s maid of honor. Mattel gave Midge an impressive dowry for the occasion that included a fashion trunk, a chapel reminiscent of the ceremonial temple in Midsommar, and multiple Wedding Day outfits; she even had a lingerie set for the big day.

When Ruth Handler created Barbie in the late ’50s, she was inspired by the way her daughter Barbara played with paper dolls, imagining them in adult scenarios. This—along with her inhuman waist-to-hip ratio and perfectly tanned hot dog legs—was Barbie’s whole deal. She was a Helen Gurley Brown girl, coming of age in the era of Sex and the Single Girl, as Lord explains in Forever Barbie:

If Barbie wasn’t already Brown’s paradigm, her self-help books suggest that becoming it was her goal. The Single Girl, Brown wrote, “supports herself.” She also keeps fit and roams the earth on her own; it’s fun to meet men in new places. Hence Barbie’s reading: How to Get a Raise, How to Lose Weight, and How to Travel—titles reminiscent of Brown’s chapter headings—”Nine to Five,” “The Shape You’re In,” and “The Rich, Full Life.”

That particular collection of reading material came with a babysitter Barbie introduced in 1963; a compromise Handler made in response to demands that Barbie have a baby. “Pregnancy would never mar Barbie’s physique nor progeny compromise her freedom,” Lord writes of Handler’s early feminist stance on the doll. “Just as she does not depend on parents, she would have no offspring dependent on her.” As if to punctuate this point, that same year, a single and self-sufficient Barbie moved into her first Dream House—a home with multiple rooms and amenities, none of them for plastic children. 60 years later, my mom has the nerve to wonder aloud why I’m still not married, and why I’m raising two cats instead of a child. (It doesn’t help that I refer to the younger cat as “my human son.”)

The feminist ideals of Barbie’s upbringing were only slightly less narrow than her waist, but they opened a world of possibility that allowed the doll to become a multi-hyphenate icon. No one batted an eye when Barbie and friends became dentists, professional skiers, mermaids, or hair stylists. In children’s bedrooms, Barbie was an independent woman with a house, a camper van, and a stocked refrigerator. She could have Midge’s leftover wedding cake for breakfast and spend the afternoon riding around in her Jeep with a freakishly small panda bear she befriended on safari. My dolls often had the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles over for pool parties. Like Barbie, I contain multitudes.

In 2002, Britney Spears was making her big screen debut in Crossroads, Star Wars fans were performing complicated mental gymnastics to convince ourselves that Attack of the Clones wasn’t actually bad, and low-rise jeans had a stranglehold on the economy. I was off dolls and on the internet, oblivious to breaking news in the world of Barbie: Midge was pregnant.

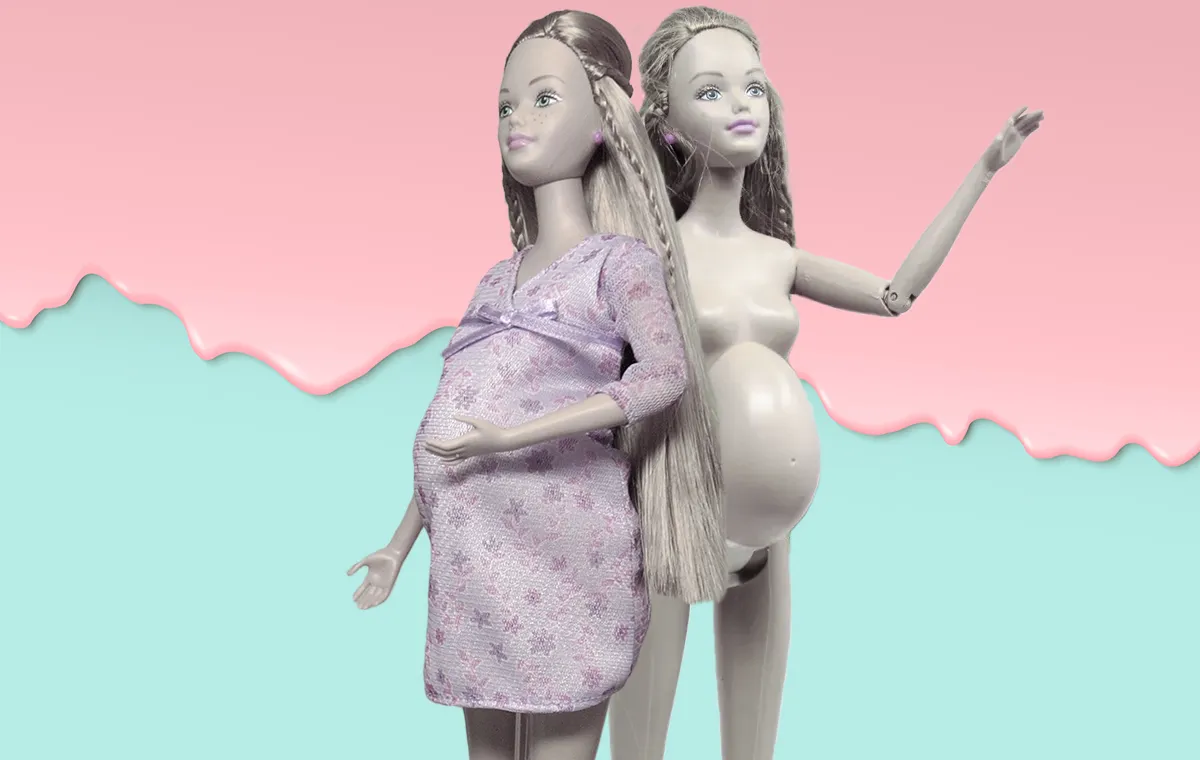

Mattel’s Happy Family line featured a pregnant Midge, complete with a removable magnetic belly and a baby small enough to fit inside. It was comically unrealistic, but the logic made a certain kind of sense in a world without nipples and genitals. Pop the belly off, take the baby out, and poof, Midge is regular again.

Happy Family Midge was sold with her new baby, or you could get the pair as part of a larger set that included Alan and their toddler son, Ryan. It didn’t seem like a big deal. For decades, kids had been playing with baby dolls that could pee out of weird crotch-holes and adopting infants from cabbage farms. Midge’s magnetic baby bump fell somewhere in the middle on this spectrum of pretend-parenting. But some real parents were real pissed about the pregnant Midge—specifically the one sold separately from Alan.

That December, Walmart pulled the pregnant version of Happy Family Midge from shelves following complaints. “It was just that customers had a concern about having a pregnant doll,” a Walmart spokesperson told CBS News. Bill Boehmer, the manager of a KB Toys store in Philadelphia, told CBS that he hadn’t received any complaints about the pregnant Midge or her Happy Family. “I’ve had people laugh, but I haven’t had anyone say this was ridiculous or ‘What are we trying to tell these kids?’ or anything like that,” Boehmer said.

Mattel’s website promoted the pregnant Midge as “a wonderful prop for parents to use with their children to role-play family situations—especially in families anticipating the arrival of a new sibling.” Some parents didn’t see it that way. “It’s a bad idea. It promotes teenage pregnancy,” one mother told CBS. “What would an 8-year-old or 12-year-old get out of that doll baby?” Honestly? Some new storylines for their dolls and a functional understanding of magnets.

Speaking with the Philadelphia Inquirer, another mom suggested, “Maybe if they would have put them all together as a family, it might be a little different, but alone it sends out the wrong message.” The problem, at least for some parents, wasn’t that Midge had gotten herself knocked up, but that Mattel was selling a version of the pregnant doll sans husband. Even though Alan and their son were represented on the packaging and Midge had a wedding ring painted on her finger, selling Midge separately from a family unit implied a sinfulness better suited for MTV and Lifetime Original movies.

By the time pregnant Midge was yanked from Walmart shelves in 2002, children had been playing with baby dolls for more than 150 years. Little girls cradle, swaddle, change, feed, burp, and coddle dolls made to look like babies. They prepare plastic food for their plastic babies in plastic kitchens and go through the superficial motions of nurturing a make-believe family in a simplified heteronormative roleplay. Why is it acceptable for a kid to pretend they’ve had a baby, but unacceptable for them to play with a doll that has a baby of its own?

It’s not as if Midge was the first doll to get pregnant. She was just the first of Barbie’s friends to get pregnant—which likely contributed to the heightened scrutiny, especially since Barbie herself would never have children, per Ruth Handler’s wishes. In 1991, a manufacturer in Denmark released the Judith Mommy-to-Be doll. Distributed exclusively in the U.S. by Judith Corp., the Judith doll came with a snap-on baby bump and a little infant curled up inside. According to an article about the doll’s debut in The Chicago Tribune, the Judith Mommy-to-Be is believed to be the first pregnant doll released in the U.S. Egil Wigert, president of Judith Corp., bought the rights to sell the dolls stateside after discovering them on vacation in Norway, where they were incredibly popular.

The Toy Box Philosopher blog published a detailed breakdown of the Judith Mommy-to-Be in 2016, including photos of the African-American version of the doll (whose baby had red eyes), the original packaging (which proudly touts “FLAT STOMACH AFTER BIRTH”—a can of worms I simply cannot open right now), and a side-by-side comparison with Happy Family Midge.

There were concerns about the Judith Mommy-to-Be doll, too, just not from conservative parents. “It’s really quite inappropriate for children—even bizarre,” child psychiatrist Gary Pagano told the Tribune. “It distorts the anatomy and the process of birth.” Which part, Gary? The FLAT STOMACH AFTER BIRTH or the part where her belly snaps on and off to reveal an abnormally large newborn infant? Dr. Bennett Leventhal, a professor of psychiatry and pediatrics, had a more measured response to the Judith doll. “Most children know where babies come from,” he said. “The answer to how it got in there and how it gets out is up to the parents.” An extremely reasonable opinion.

“The feedback we received from kids and parents alike was that kids often try to make their regular dolls look pregnant and then pretend that a smaller doll is the baby they nurture,” Wigert, the president of Judith Corp., told the Tribune. Dolls have a long history as props in cultural storytelling that dates all the way back to early civilizations. In her book Dolls, the author Antonia Fraser found evidence of dolls placed in Egyptian tombs as early as the 21st century BC. The modern baby doll arrived in the late 19th century, followed by Barbie in 1959. In the decades since, dolls and action figures have become part of elaborate narratives; nascent works of fan-fiction dreamt up in childhood bedrooms all over the world.

Modifying dolls is one of the great traditions of doll ownership. A 2005 study conducted by the University of Bath found that girls aged seven to 11 “routinely mutilated” their Barbie dolls. The ritualistic butchering of Barbie’s hair, the desecration of her rubbery limbs with tattoos inked in pen, the piercings achieved with safety pins and sewing needles. I dyed the hair of my Barbie dolls with Kool-Aid and gave them goth makeovers with finepoint Sharpie pens. The desire to modify dolls isn’t taught or inherited, it’s innate; a natural urge, like licking your fingers after eating an ice cream sandwich on a hot day. Online, you can find blogs dedicated to more elegant Barbie modifications, including DIY baby bumps made from plastic Easter egg shells.

Greta Gerwig’s Barbie, the live-action movie based on Mattel’s iconic doll, pays tribute to the unhinged aesthetic of the modified childhood Barbie. In the film, which stars Margot Robbie as the primary, classic iteration of The Doll, Kate McKinnon plays Weird Barbie, a Barbie whose hair has been chopped and screwed and whose body is covered in streaks of marker. This Barbie clearly survived a harrowing encounter with a toddler. Barbie also pays homage to Happy Family Midge. Emerald Fennell, who wrote and directed Promising Young Woman, plays the pregnant version of Barbie’s best friend. (Michael Cera plays her husband, Allan.)

While researching this article, I came across a fascinating niche where these two corners of Barbie history intersect: the Barbie narrative video. The elaborate roleplay videos often depict Barbie, Ken, and their friends doing extremely normal activities, like going to the store, visiting family, and getting ready for bed. Some of the videos, like those from popular YouTube creator Jess The Barbie, are filmed in the style of family influencer vlogs. There are even scenes where characters speak directly to the camera, recapping events. Between going to the dentist and taking the dog to a park, dolls confront one another over infidelities and cope with distressing situations. In one series of videos, young Amelia goes missing. In another video, a gender reveal party goes horribly wrong.

Of course, pregnancy is a recurring plot point, as is the case in the aptly-but-clunkily titled “Pregnant Barbie gives birth to her twins! Emergency C-Section! – *Fake Surgery*”

What’s striking about these narrative videos isn’t the content, but the attention to detail—not only in the set design (pregnant Emma wears a tiny blood pressure cuff; there’s a diagram of a fetus on the wall) but also in the dialogue. As Emma the doll writhes in agony, medical staff fret over whether or not they can safely administer an epidural. (That attention to detail leaves the building when we see the newborn twins, who are clearly not related.)

On the other end of the Barbie narrative video spectrum lies madness. An account called FUN2U, which generates gaudy content for younger viewers seemingly based on popular search terms—mermaids, pranks, how to be popular—has the most bonkers depiction of pregnant Barbie: “My Avatar Doll Is Pregnant / Barbie Doll Makeup Transformation”

Part DIY tutorial, part narrative roleplay, this video does not start with anything resembling the vibrant landscape of James Cameron’s Pandora. A blonde woman, dubbed in English, unclogs her sink to discover a Barbie covered in glitter-slime and decides to clean her up: she pops her tiny pimples, scrubs her face, and then takes the chewing gum out of her mouth to wax the doll’s legs—which are covered in hairs of dubious origin. Following an extended salon sequence, the woman pulls a tiny doll modified to look like a baby Na’vi out of a fish-shaped box (of course!) and is immediately inspired to transform her Barbie. “Let’s make you an Avatar!” she exclaims, and at this point, you really have no choice but to follow her logic.

The excitable blonde woman paints the Barbie blue, braids her hair, and gives her a sparkly pregnant belly. She also smartly gives the doll a tail—how else is she going to get pregnant with this Na’vi baby? After all of that, the blonde woman sticks Avatar Barbie in a fishbowl because “pregnant women need rest.” Not for long, of course, because Avatar Barbie is going into labor with her Avatar baby.

There are others: Barbie is pregnant with a bird creature. Barbie is pregnant with a Pikachu, and her belly looks like a Pokéball. Mermaid Barbie and Mermaid Ken are pregnant with a Mermaid Baby—which actually seems normal compared to the supernatural bird birth. If you follow this particular YouTube rabbit hole, you’ll find more pop culture characters in strange situations accentuated by garish aesthetics and cartoon sound effects. In one, a pregnant Wednesday Addams does battle with a pregnant M3GAN. The video is 31 minutes long.

While these videos are extremely weird, they feel like a modern extension of the stream-of-consciousness improvisations associated with childhood play. Mostly, knocked-up Barbie dolls seem harmless (FLAT STOMACH AFTER BIRTH notwithstanding). The genre is certainly nowhere near as disturbing as our cultural obsession with pregnancy in the U.S. In fact, it seems only natural that a pregnant Barbie would find her way into the playroom, either officially or through DIY ingenuity.

Our infatuation with pregnancy is simultaneously puritanical, preoccupied with heteronormative conventions and gender essentialism; morbid, especially now that abortion is functionally illegal in several states; and invasive, guided by a news media that documents the fall of Roe v. Wade in one headline and heralds the latest celebrity pregnancy in the next. (Presumptuous headlines announcing a celebrity’s “first” pregnancy are particularly egregious.)

The media treats the pregnancies of strangers as a topic fit for public consumption and discussion, but being pregnant is intrinsically private. A prenatal belly is suggestive of a hidden, deeply personal reality we’re not privy to—despite the sense of entitlement coddled into our brains by tabloids and magazines. In a sense, the Lindsays and Britneys and Beyoncés of the world have replaced the Barbie dolls of our childhood.

Given the existential and visceral horrors of pregnancy in the U.S., and our unhealthy fixation on the reproductive lives of total strangers, maybe we should feel relieved that pregnant Barbie roleplay has managed to remain so … silly. That something like “My Avatar Doll Is Pregnant”—a truly deranged work of narrative short-form media—is the most unsettling product of this fascination is pretty astonishing, all things considered.

(featured image: Lawrence Lucier, Getty Images / Mattel / eBay / Illustration by The Mary Sue)

Published: Jul 21, 2023 12:42 pm