(TW: Discussion of rape and sexual assault)

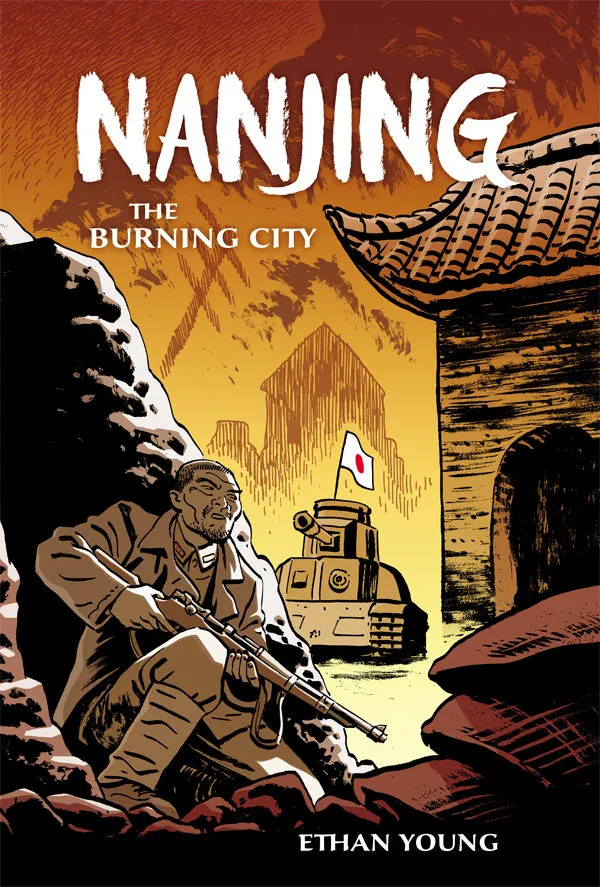

On December 13th, 1937 Japanese troops captured the former capital of China, Nanjing during the Second Sino-Japanese War. From there began a 6 week long massacre full of torture, rape, and mutilation that claimed an estimated 300,000 Chinese lives. It’s a horrific episode in history that not many people know about, which is why I was really curious about Tails creator Ethan Young portraying it recently as a comic at Dark Horse. We spoke about the format, his character, and why it’s still important to tell this story “for the forgotten ones” almost 80 years later. You can watch the book trailer here.

Charline Jao (TMS): Someone uninformed about the Nanjing massacre would have a slightly different experience from someone who knew about the subject reading your book. Who do you feel was the intended audience for this book and how conscious were you as a mediator?

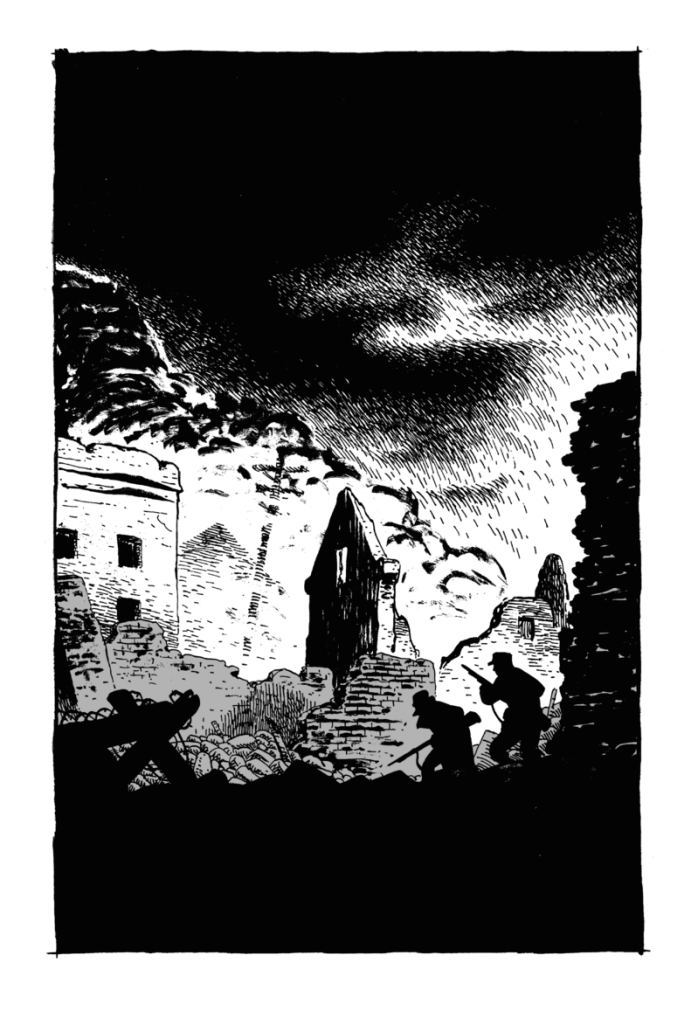

Ethan Young: Definitely the uninformed members of the audience. China’s involvement in WW2 is so glossed over in our history books, along with most of Asian American history. For people who are already familiar, there’s nothing groundbreaking for them, but the graphic novel might serve as a good primer they can lend to interested parties. I wanted an uninformed reader to feel at ease while reading, which can be difficult given the graphic nature of the content. That’s a big reason why I employed so many silent scenes. It lets the story breathe and unfold on its own. In silence, the reader can just be more of a witness than a participant.

TMS: You wrote the first graphic novel about Nanjing Massacre. Do you feel like there’s something specific about comics and the graphic novel medium that helps tell this story?

Young: I think the ability to choose your own pace is the greatest benefit of comics, especially for a subject that takes such an emotional toll. Your individual ability to control the speed of the story means you’re ultimately in control of the tension.

TMS: You said that you had shelved the project for awhile until you felt equipped to tell it. What was it that made you feel ready to tell the story?

Young: Just some overall maturing I had to do. Not that I can speak for every 20 year old artist, but I was definitely an arrogant guy with an inflated ego. Different levels of failure and success humbled me by my late 20s, and I finally felt ready to approach the story with a level-headed sensibility in my 30s. I’m still working on my maturity day to day.

And in addition to that, just being a much better artist really helped. Knowing what to draw, how to draw it, and how to present it. These were things that escaped me during my first go. My initial sketches for this project aren’t just crude, but a little tone deaf as well. It’s takes a more developed storyteller to differentiate between drama and melodrama.

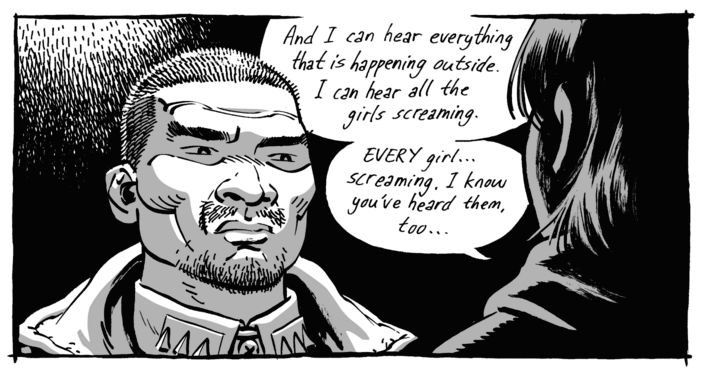

TMS: The sexual violence during the Nanjing Massacre was a big part of what made it especially heinous. How did you go about drafting and representing this violence? And more broadly, how does a creator handle a topic as sensitive as this accurately but respectfully?

Young: Personally, I believe our minds paint the worse pictures we can imagine. Like Shawshank Redemption for example. You never actually witness Andy’s assault, and it’s never even spelled out in precise words, but it’s very clear what has happened. You feel horrible without ever having seen the assault. That was pretty much my method. Some people have expressed that my book was too graphic for them, while others felt that I didn’t show enough brutality, so my book is up for debate.

I feel that too often, sexual assault is used as a cheap gimmick to titillate, and it really desensitizes the audience. Which isn’t healthy, in my opinion. If a younger creator is thinking about including this very real and harsh subject in their work, I think the most important question to ask yourself is: who benefits from this story element? Are you speaking up for survivors of sexual violence? Are you doing this for shock? Have you talked to survivors and listened to their lived experience? Give it a thorough examination, because that’s the least you could do. Don’t just recreate a scene you saw on Game of Thrones.

Ultimately, it’s a free country and you can do whatever you want. But as a creator, you’ll have an engaged audience, which means you’ll have a responsibility. People internalize the media they consume. And please, stop with justifications such as “well, it happens in real life.” That may be true, but so does violent diarrhea, and I’m not interested in seeing that on screen either.

TMS: I imagine it was a very emotionally taxing experience to do research when so much of the literature and media around the 2nd Sino-Japanese War has a tendency to be very anti-Japanese, and I know you were consciously trying to avoid that. Was it difficult to stray away from those sentiments?

Young: I won’t lie, it was at times. Even into my late 20s, I still had some leftover anti-Japanese sentiment that I had to work through, even if I claimed to know better. You tell yourself you can make the distinction between the people and the soldiers who committed the atrocities, but sometimes those lines become blurred, especially if you view an incident through the lens of nationalism. Back in high school, my Asian American friends were all of mixed nationalities, and we threw around explicit Asian slurs to one another. In that “these are our words’ kinda way. It also normalized passive aggressive inter-Asian animosity for us. At some point, I read Shigeru Mizuki’s Showa. Though it was just one book, hearing a Japanese veteran condemn the actions in Nanjing painted a broader picture for me.

TMS: The civilian character, Yan, really stood out to me in this narrative centered on male soldiers. Can you talk a bit about how you created her character and her role in the book?

Young: I was mostly inspired by the documentary Nanking, where many survivors were interviewed. This one woman told a gut-wrenching story of sacrificing her body to a Japanese soldier so that her grandpa would be spared. There are many accounts of brave, defiant women in the midst of war, so I just wanted to acknowledge that in some small way. Also, my mother and I are very close, so Yan was an embodiment of strong Chinese motherhood. I guess folks now call that Tiger Mom here.

TMS: A lot of dialogue around these narratives have a tendency to revolve around the ultimate goal of reparations, or a public apology, which I felt you avoided. Was that the case? And if so, why is it still important to tell the story of the Nanjing Massacre now?

Young: You’re right, I didn’t want to be didactic. As I mentioned before, it’s very easy – and dangerous – to be drawn into extreme nationalism. Sino-Japanese relations are still contentious and complicated, and I wanted to reflect that. Although the Imperial Japanese Army played the largest role in the atrocity, the Kuomintang was corrupt and did some immoral things as well, which played into their enemies’ hands. Outside of a few select characters representing pure good and pure evil, I wanted our main characters to be morally ambiguous.

But the book also serves as a snapshot of war, and how war engulfs the individual, whether they be a disillusioned soldier or a refugee. We see the patterns repeated over and over again throughout history, so I wanted to take this isolated tragedy and weave it into a narrative that applies to a lot of conflicts. Which sadly, it still does.

TMS: What kind of reception has the book gotten since its release and how do you feel about it? I’m especially curious about how you reacted to the Nanjing-denier that messaged you.

Young: Haha, that was certainly an amusing experience. The denier actually tweeted Dark Horse and Jim Gibbons (the book’s editor) directly, I just got to witness it. I think I’ve reached a very zen place in my life where I’ve accepted the pointlessness of arguing over the internet, so I didn’t even bother. This person clearly made up their mind and was adamant about it. I was a little pissed, but I just decided to move on.

Other than that, most of the response has been overwhelmingly positive, and I’ve even had a few readers of Asian descent personally thank me for making this book. A lot of libraries and teachers have also responded well, and I couldn’t be more grateful on that front.

TMS: I heard a bit about your next project through this Bleeding Cool article. Can you tell me anything about your next book, the sci-fi Mulan-based story that touches on China’s one child policy?

Young: Sure! Because of some legal hiccups, I can’t actually use the name Mulan, but the folktale of a female warrior is the backbone to my next book. It’s essentially about a seasoned military nurse who has to defend an outpost from an invading alien force. It’s a straight forward sci-fi setting, which I’ll use as a platform to explore topics such as China’s now-repealed one-child policy. Although, I think I may have slightly oversold that aspect of the story.

I’m not tackling the one-child policy per se, but the unintended consequences of that policy, such as the reinforcement of China’s cultural preference of boys over girls which resulted in an initial explosion of orphaned girls (but over the years you saw more boys being abandoned, especially if they were sick or disabled). That’s the element my next book will explore, the displacement of children, and a society’s preference for boys over girls, and what kind of dynamic that might build in a futuristic world. I just figured a Mulan-type figure would compliment that topic.

It’s YA and shorter than Nanjing, so I have to squeeze a lot of story, nuance, and action into a smaller package. I’ll get to do more volumes if it’s successful. I’m hoping to explore the topic further, and have the characters evolve in this world organically.

Nanjing: The Burning City is available on Dark Horse and an absolutely worthwhile read.

(images via Ethan Young)

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Published: Dec 14, 2015 01:08 pm