Hal Hartley has been one of the most respected independent filmmakers since coming onto the scene with his romantic dramas The Unbelievable Truth and Trust, both starring the late Adrienne Shelly in her first leading roles. Eight years later he had his biggest success with Cannes Award Winner Henry Fool (best screenplay), the story of an ex-convict (Thomas Jay Ryan) who squats under the home of the Grim family and befriends siblings Simon (James Urbaniak), a garbage man Henry convinces to take up writing, and sister Fay (Parker Posey) whom Henry eventually marries.

Hartley continued the story of the Grim family’s dark, tragically-comic life with Fay Grim, with the leads returning alongside Jeff Goldblum and Saffron Burrows. Liam Aiken takes the lead in Ned Rifle as the son of Henry and Fay. Returning at 18 from witness protection a devote Christian on a mission to kill his father, and meets a young women (Aubrey Plaza) who is just as desperate to find Henry. Former child star Aiken started his career with Hartley, playing Ned in Henry Fool 18 years ago, making him one of many Hartley’s regular actors along with Martin Donovan, Bill Sage, Robert Sean Burke, Karen Sillias, Ryan, Posey, and Urbaniak; returning for the final chapter of the Grim Family Trilogy.

Hartley spoke to us of finishing the family drama, the upcoming tribute hosted by LA’s Cinefamily, and some of the fascinating female characters he’s put on film.

[Editor’s Note: Spoiler Alert – This interview contains some plot discussion about Henry Fool in regards to Plaza’s character. The information is necessary going into Ned Rifle and addressed in the trailer.]

[Editor’s Note: Spoiler Alert – This interview contains some plot discussion about Henry Fool in regards to Plaza’s character. The information is necessary going into Ned Rifle and addressed in the trailer.]

The Mary Sue: Before speaking with you, I re-watched Henry Fool and immediately watched Ned Rifle. Watching the movies, I have to admit, it was emotional to see Liam as Ned as this little kid and then as an 18 year old. It kind of gets to you.

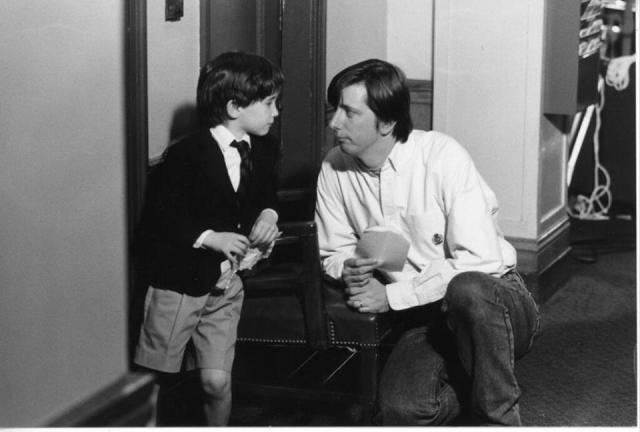

Hal Hartley: Yeah, I’m just so happy he grew up and still wanted to be an actor. When we made Fay Grim, he was 16 or 17 and I took him out to lunch to reconnect and find out what his plans were for the future. And at that time, he wasn’t so sure. He was in a rock band but he was still acting. But trusting my own instincts, he looked to me like someone who would grow up to be an actor.

TMS: When you decided it should be a trilogy, did you know it had to end with seeing who Ned became?

Hartley: Oh yeah, definitely. When I decided I would make more films about these characters, I imagined it should be three films, not two. And if the second would be about Fay, the third one should be about their son Ned.

TMS: And it provides a nice book end because you can see in the character all the influence the people in his life have had on him; his dad, his mom, his uncle Simon, the foster family.

Hartley: Definitely. And I always loved the scenes between Ned and Simon, way back in Henry Fool, and especially in Fay Grim when they have a lot of scenes together, being the detectives back at the house in Queens.

TMS: Liam turned into a really good actor, but directing a child actor is not the same as directing an adult actor. Were you at all concerned that he or Aubrey, being new to your style of filmmaking, would have trouble with your style of directing?

Hartley: It was a concern, not for very long though. She got attached very late, after I raised the money, and I was announcing everywhere very loudly, “I’m looking for the new leading lady.” And I spent months auditioning women, and put at least 60 or 70 on tape both in New York and Los Angeles. And I met some great actress, and a lot of them show up in the movie in other places. But I just didn’t find anyone who was right for the role of Susan. But my conversations with her agents led to them suggesting her, and I watched what I could of her and decided I should speak with her. We had a conversation on the phone after she read the script and she was very excited to do it, but I asked her, “do you know anything about my films?” and she said “I’ve seen The Unbelievable Truth”, which is from 25 years ago. And then she told me a friend told her about Henry Fool which she was planning to watch the next weekend. And I told her that I do something particular with the lens.

My films are not improvisational, so you really have to know the text, and my direction is about moving very specifically, we block very specifically. And she said she was game. And before she came to set, she called Parker Posey, who she knows somehow, and asked “what do I need to know about this guy?” and Parker said “you have to know your dialogue inside and out, he’ll take care of everything else, but you have to know your dialogue.” So she did. The first day, I think she was a little nervous when we did start blocking, because I was telling her when to move here arm and sit down or stand up. But it’s not like I’m impose it, I’m seeing it in the way the characters move. But she was a little breathless after a couple of takes, and at the end of the day, I showed her the monitor and she got it.

My films are not improvisational, so you really have to know the text, and my direction is about moving very specifically, we block very specifically. And she said she was game. And before she came to set, she called Parker Posey, who she knows somehow, and asked “what do I need to know about this guy?” and Parker said “you have to know your dialogue inside and out, he’ll take care of everything else, but you have to know your dialogue.” So she did. The first day, I think she was a little nervous when we did start blocking, because I was telling her when to move here arm and sit down or stand up. But it’s not like I’m impose it, I’m seeing it in the way the characters move. But she was a little breathless after a couple of takes, and at the end of the day, I showed her the monitor and she got it.

TMS: The character she plays, Susan, was mentioned in Henry Fool, when he explained why he went to prison. Why did you decide to finally show Susan as a real person and make her a main character in this film?

Hartley: In Henry Fool, all of the time in that movie, he’s a lovable slob. Except that moment when he confesses to Simon that he was in prison for having sex with a 13 year old girl named Susan. And especially the way he talks about the girl, as someone who took advantage of him. It’s what I wrote, but some combination of the script and what Tom and I did with that scene, brought up ideas which were never really addressed. The creepiness of this man saying he had been wronged by this kid. And I always thought, re-watching the film over the years, that it was a subject matter that we could have expanded on, but didn’t. And maybe it wouldn’t have been the right time to dive into that, but it stayed with me.

But I kind of forgot about it over the years, until I was working on the script for Ned Rifle and most of the plot was there; the idea that Ned was now a Christian but was going to go out and try to kill his father for everything he’d done to his family. But it still didn’t have something, it needed some weight, so I went back to watch Henry Fool again and this time decided, we needed to go all the way back, seven years before that movie starts when Henry went to prison for having sex with this kid, and let the girl have her say. And I always suspected, funny to say you suspected something you wrote, but I suspected that Henry became Henry Fool the intellectual in prison. He invented the misunderstood genius because of the shame, regret, and embarrassment over what he’d done. He invented that persona, and that was how he played it, so when he realizes who Susan is, that persona drops.

TMS: Did the fact that the film focused on the two kids whose lives were impacted by the choices and mistakes of adults we’ve been following in the other films impact the tone or style of the film?

Hartley: I think it did, whether it’s terribly obvious or not. A character like Ned provided me with a good tool to reassess these characters, because I gave him a very different sense of morality than his dad or mom or uncle. And because of that, he can ask these really straight questions that go to the core, such as the conversation he has with his uncle Simon about the standup comedy, when he asks “why are you doing this?” It’s as if no one cared or thought it was there right to suggest to Simon that this was a waste of his talent. But because he has this willfully simple morality, and he’s righteous at that point in the film, Ned can ask those questions. In the really part of the film he’s a righteous Christian so he doesn’t hesitate to speechify. So there is something about that. And I liked the way James played those scenes with Liam. Simon is essentially the center of this universe, he’s the poet, and he’s having some kind of nervous breakdown and wants to be stand-up comic. But if you bang his head around, he’ll come back to the important things and he’s never judgmental. He says to Ned “wow, you found God, I would never do that, but I’m curious.” and that’s how he gets back.

TMS: The women in your films have become somewhat iconic of women from a certain era in film, starting of course with Adrienne Shelly and later Parker Posey. Did you notice any similarities that Aubrey fit into that describe the type of female characters you create?

TMS: The women in your films have become somewhat iconic of women from a certain era in film, starting of course with Adrienne Shelly and later Parker Posey. Did you notice any similarities that Aubrey fit into that describe the type of female characters you create?

Hartley: Yeah, I definitely do. When I saw the movie she did, Safety Not Guaranteed opposite Mark Duplass, that’s when I said to myself “this girl has the charisma I’m used to.” It’s hard to describe, but it’s not an over emphasis on interpretation. What a lot of people call deadpan, although I never use that term. But it can be kind of a neutral trust of the words, and not underlying the words with some kind of verbal expression. But also she had a certain look; a certain kind of prettiness.

TMS: Knowing your film, there is always a scene of women putting on make-up, at the very least lipstick. Is that some kind of shield you give them, because they tend to put it on somewhat aggressively, as if it’s a kind of war paint?

Hartley: You’re onto something there. It’s an announcement of their kind of intentions at that moment. Adrienne Shelly’s scene in The Unbelievable Truth, I just thought would be hilarious that she is trying to seduce an older man and has no idea that she has this streak of lipstick on her face as she’s trying to be sophisticated. I think it took on a different intensity or color in this film, because when I wrote Susan, I didn’t think of her as being as overtly sexual as Aubrey played her. Aubrey came to town with her own clothing, and after working with our costume designer, she said she had her own ideas for how Susan should look. She wanted to wear high-high heels and leggings and stockings. And I said okay, you look great, let’s go with it. I think my idea in the script was that Susan was kind of more inept. You see those characters a lot in movies, the people so busy thinking, they don’t button their shirts the right way and put their lipstick on wrong. But this time, it became almost a mania. I guess she just took that line, Parker’s line “she’s addicted to lipstick” and ran with it, treating the lipstick like an alcoholic, who can’t help but put the lipstick on.

TMS: There is also something kind of sad about watching this young woman trying to present herself as a put together adult and pretty much failing.

TMS: There is also something kind of sad about watching this young woman trying to present herself as a put together adult and pretty much failing.

Hartley: Yeah, she’s not entirely within herself a lot of the times.

TMS: One of the things I’ve read, and I have to paraphrase, is that the men in your films won’t speak until they’ve formulated the exact words and intentions, which is why many men are rather silent, whereas the women start talking and find the meaning as they’re talking, and seem like such extroverts. Is that true of your writing process?

Hartley: I don’t think I’m organized about that, but it does sound like something I think about when writing, because it’s always a struggle when writing dialogue, asking yourself she or he wants to say at this moment? Are they trying to answer the question or get around the question? Or are they not listening when pursuing their own thoughts. I know I’ve done things like that, even in this film. Susan never knows what she wants to say at the start of a sentence or when she’s going to finish.

TMS: And it’s certainly true of the Grim siblings Fay and Simon. Fay can’t shut up, even to her own detriment, and he can never get the words out.

Hartley: She’s totally instinctual. And James and I have always discusses Simon that way, as a man who has to think every word though before he speaks. He has to visually see the idea he wants to express, and that started all the way back with Henry Fool, when discovering things about the way Simon moved or spoke, and in the early part of the film didn’t speak.

TMS: Cinefamily is hosting a month long retrospective of your films, including a gallery of film stills and photographs. Have you been a part of the plans for this event?

Hartley: They got all the images from me. The images were made by this artist named Philip Reilly, who makes these collages and sculptures, but also prints photographs to a massive level. And a couple of years ago he approached me, knowing I had a huge archive of photographs, and said “I’d like to take about 200 photographs and make them big and make objects out of them.” And he has a space in Williamsburg Brooklyn, and he put on a show for about two weeks. And what was left over were about 30 images, so that is what will be on display. Cinefamily approached me about the movies they’d like to show, and then asked “are there any images you can provide” and I said “well, I have these.” And I think they might be showing some drawings I make during production as well.

TMS: This being a retrospective of your work over the years, were there trends or themes that you realize you touched on repeatedly that you hadn’t noticed or thought about before?

TMS: This being a retrospective of your work over the years, were there trends or themes that you realize you touched on repeatedly that you hadn’t noticed or thought about before?

Hartley: I don’t think so. As I’ve made films over the years, its become clear over the years, that my core ideas and themes I’m interested in address, doesn’t deviate that much. Somehow, in the 80s, when I first started making movies, I saw the light and haven’t really deviated that much. That’s why felt confident in the early 2000s to experiment with genre, and made a sci-fi movie, a monster movie, an espionage thriller. Because I knew they weren’t really these genres. I was just using superficial elements from these genres as a kind of short hand, which I thought would be kind of fun and lighten up the treatment of fairly heavy subject matter.

TMS: On the top of the monster movie No Such Thing, which was my first exposure to your films, soon after you worked with Sarah Polley she directed Julie Christie (also in No Such Thing) in Away from Her and has become a very talented writer director herself. Adrienne Shelly became a writer director soon after you worked with her. Have you provided guidance to up-and-coming writer-directors?

Hartley: Probably not on their level. I’ve taught filmmaking in a classroom environment and some of those students have become filmmakers or TV directors or documentarians. But probably the closest creative collaborator I’ve had is my editor Kyle Gilman, who was a student of mine, who intended to become a filmmaker, but he outgrew that and learned to edit and became very gifted at that. But besides Sarah and Adrienne, I haven’t really worked with people who became writer-directors. Besides Martin Donovan who did direct a movie called collaborator and directs some TV.

___

Ned Rifle is available on demand on Vimeo today and the Cinefamily honors start Friday.

Lesley Coffin is a New York transplant from the midwest. She is the New York-based writer/podcast editor for Filmoria and film contributor at The Interrobang. When not doing that, she’s writing books on classic Hollywood, including Lew Ayres: Hollywood’s Conscientious Objector and her new book Hitchcock’s Stars: Alfred Hitchcock and the Hollywood Studio System.

Are you following The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Published: Apr 1, 2015 08:00 pm