Interview: Bones Composer Julia Newmann

On writing music for film and TV and working in a male-dominated industry.

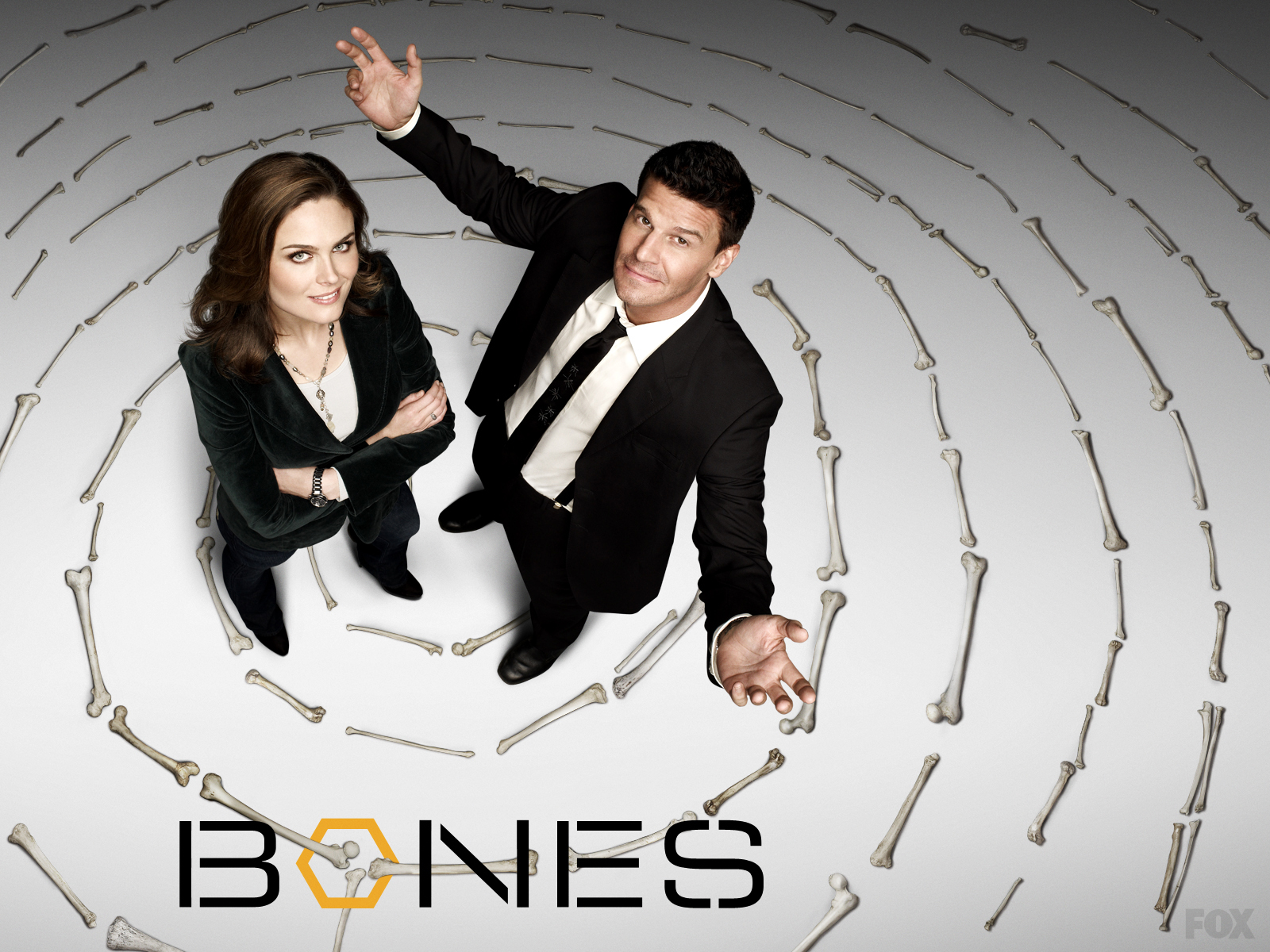

Since its premiere in 2005, popular television series Bones has delivered one of the most consistently smart and complex female protagonists on primetime, Dr. Temperence “Bones” Brennan. Created by Hart Hanson and loosely based on the writings of real-life forensic anthropologist Kathy Reichs, the show is now in its 11th season and is the longest-running one-hour drama series produced by FOX.

Since its premiere in 2005, popular television series Bones has delivered one of the most consistently smart and complex female protagonists on primetime, Dr. Temperence “Bones” Brennan. Created by Hart Hanson and loosely based on the writings of real-life forensic anthropologist Kathy Reichs, the show is now in its 11th season and is the longest-running one-hour drama series produced by FOX.ASCAP Award-winning film and TV composer Julia Newmann has worked on 8 seasons of the show and kindly took a breather from sprinting towards her weekly Bones deadline to speak with us about her work, the inspiration behind her music, and the importance of supporting other female composers in film and TV.

Jaimie Li (TMS): You’ve worked with composers Sean Callery and Jamie Forsyth to score 8 seasons of Bones, which is now in its 11th season. How did you get started, and what has it been like to work on a show for so many years?

Julia Newmann: I started in 2008, and I was only 26 or 27 at the time. This was my first TV show, and I was incredibly lucky that Sean asked me to come on board with him on this series. When we started out, Sean, Jamie, and I developed a new sound for the producers, who wanted something a little more orchestral, dramatic, and showed a wide range. Sean knew I had a film background in scoring, and he wanted to bring that in there. He had a lot of faith in me, and he’s been a great mentor and cheerleader.

It’s definitely been an evolutionary process, as the score has evolved with the show. TV is much faster paced than film, and I’ve had to learn to work more efficiently. In film, you have weekly meetings to go over the progress of your work, and with TV we have 5-6 days maximum per episode. One of the challenges of a long-running show is show to keep yourself creatively inspired and keep it fresh while balancing life and these deadlines.

TMS: You mentioned that the producers wanted a new sound for the show. How would you describe the Bones sound?

Newmann: It’s a hybrid of styles. There’s a lot of shifting of tones in the show, and a wonderful part about this particular series is that there are a lot of opportunities for different styles of music. In an average episode, I get to do horror, investigative, mysterious, romantic, and quirky, sometimes all mixed up into one scene! The horror scenes are really fun because the producers really get into make those scenes as gross as possible, and they like the music to sound gross as well. That’s where I get to be really creative and experiment with really strange sounds for disgusting corpses.

The comedy is probably the hardest. You have to have good comedic timing, and avoid nailing it on the head too much. Thomas Newman has definitely been an influence on us in the way that we’re treating comedy. It’s a little bit more modal, to use a musical term. The producers didn’t want it to be too “Mickey Mouse” in terms of humor and try to go just neutral enough, quirky and interesting. I do a lot of stuff with mallets/marimbas and layering these elements with pizzicato strings and pulses and occasional wind instruments. I would say tonality-wise too, I’ve been inspired by Thomas Newman’s scores for some of the more emotional music for the show as well.

The series has definitely evolved, and so has the music. We’ve gotten a little more subtle than we used to be. The producers really like Homeland, and we’ve brought an element of that kind of textural minimalist type of sound into the ambient-slash-investigative portions of the score at times, which has been really effective.

TMS: How versatile are you allowed to be with the music on Bones?

Newmann: Working on any series for 8 years, you have to figure out how to keep yourself creatively inspired, because repetition happens and that can get stale. With Bones, the producers like to keep it fresh which helps us to push and find new things. There are some “exotic” episodes that will take place in different areas and locations. One episode features a circus in Texas, so we had to do a cowboy-slash-circus type of music mixed up with the Bones style. We’ve had a Japanese episode, so we brought in my husband to record the shakuhachi [a Japanese bamboo flute] for it. We’ve had an Amish episode, which was also really fun. We got to do some very earthy, emotional, solo violin music for it, kind of like James Newton Howard’s “The Village.”

The most extreme exotic episode was the 200th episode last year. The producers did this amazing thing where it was a whole 1950s standalone episode with a Bernard Herrmann type of score. We pretty much divorced ourselves from the whole Bones style of music writing to do this entirely different type of score. We got to record a live string section. It made a big difference to selling that kind of sound and making it authentic. For the average episodes, Bones is recorded from our studios using samples. There are little [live music] enhancements here and there, but it’s pretty much all electronic.

TMS: Speaking of which, it seems like more scores are being recorded electronically to cut costs and save time. Do you have a preference for recording scores electronically or the “old-fashioned way” by hiring musicians?Newmann: Oh man! I really miss working with real musicians. It’s a lot more inspiring to have that kind of collaboration and hear it come to life. But it is more challenging, and there are a lot more steps involved. Once you get the studio mock-up approved by the director, you have to arrange it for the orchestra, make and distribute parts, record it, mix it, and master it. There are just a lot more steps, but the outcome is worth it—you can’t beat the real thing. Even just adding a few real instruments in and mixing them with the synthestrated sounds can bring a richer layer which I like to do when time and budget allows. Sometimes I’ll even sing on my scores to add a human element.

But most of the time I am self-contained within my studio, and it’s nice having that sense of control. I can really control the expression of the instruments and the balance, just how I like it. Being self-contained is a little simpler, but it does make you write differently because you’re making decisions based on whether it sounds good with the “synthestrated” sounds. The sampled instruments have gotten better and better, so it’s much more palatable and fun to write in the studio environment than before, unlike when I was in college, when it was really hard to imagine the music past those horrible sounds!

So there are advantages both ways. But I do still wish that there were bigger budgets to hire musicians more regularly. Some TV shows, like The Simpsons, still have [live music]. When it happens, it’s to be celebrated!

TMS: What was some of your favorite music to write for Bones?Newmann: The music for Booth and Brennan is definitely the most interesting because there are so many layers of emotions going on between those two. For the longest time, there was that whole sexual tension thing that the writers just milked for what it was worth over many seasons. All the characters around them and the show’s audience were like, “Come on already!”

As the tension was growing, the longing for each other was as well but both didn’t want to admit it to one another because they were scared of their feelings and that it would ruin their wonderful professional partnership. We started bringing in certain themes for that feeling. There’s a certain chord progression that I came up with during those seasons to represent the longing and conflict of emotion between the two of them. I still bring it back every once in a while, especially during those scenes when they’re discussing their personal relationship, their work relationship, and [the impact they have on each other].

TMS: Do you use your real life as inspiration for your work on the show, and are there any similarities between you and the character(s)?

Newmann: Yeah, [Brennan and I] are both very career driven and passionate about what we do. Brennan feels protected by her work looking at things through science, and that’s how she makes sense of the world. In a way, I look at life with my musical brain, so I sort of interpret things differently than the average person. I start hearing music when I get inspired by nature or some sort of life event.

[Brennan and Booth] even remind me of my husband and I in a way, and sometimes

I even feel like my husband looks a little bit like Booth! Booth has this optimism to him, and she responds to him like she doesn’t to anybody else. He’s taught her to have faith, be optimistic, and not think so scientifically—I think that’s been such a beautiful evolution with her character. [That evolution] is similar to me and Cody because we met at USC when I was only 18. He’s helped me mature a lot and see things through different perspectives. I used to be a lot more anxious, and he’s helped me have more faith that things will just work out and to enjoy the moment. I’ve been a lot happier since I started trusting that, and it’s been a really cool thing. So I think the evolution I’ve had with Cody and vice versa has helped me understand Booth and Brennan’s dynamic in a personal way which has inspired my music for them. Plus we work together from time to time so I understand the mix of love and a working relationship!

TMS: Tell us more about having a “musical brain”. How did it lead you to a career as a composer?

Newmann: My grandma kind of discovered me when I was about 8. She said that she had all these music boxes around the house and she would play the music boxes for me, and then I would run to the piano and play them by ear, verbatim. I also painted as a youngster. I’d sit my paintings in front of me and would create little stories for the paintings, and then I’d add music. In a way it was kind of like film scoring! When I was about 13, I saw Legends Of The Fall, and the music was so beautiful with the scenery and this incredibly powerful story. I had this big breakthrough, enlightening moment of “Aha!” The way that music made me feel was so strong that I wanted to make other people feel the same way with my music propelling a story.

TMS: You and your husband Cody Westheimer founded music production company New West Studios in 2006. What’s it like starting your own company and working with your husband?

Newmann: Cody and I met in college before our careers even started, when we were in our learning stages. We’ve made each other better composers along the way, and it’s really nice to have someone who’s always around that I can play my stuff to and get good musical feedback! We’ve been each other’s ears at recording sessions and each other’s orchestrators on projects in the past.

The name of our company actually comes from our last names, Newmann and Westheimer, combined. He has his studio in the backyard, and I have my studio above the garage as my own creative sanctuary. We create most of our work completely “in-house” and record live musicians and license our catalogue to TV shows and films. It’s challenging to present ourselves as both a composer husband-wife team and also individual composers with separate but intertwined careers.

The beauty of Cody and I is that we have different strengths which go hand in hand

to produce a great musical outcome. We’ve collaborated on several projects together both big and small throughout the years. We recently scored on a passion project together, a documentary called Let Elephants Be Elephants which aired all across South East Asia and was nominated for an Emmy-equivalent in that region. This film is about raising awareness about the poaching crisis decimating elephants for their ivory, and its an issue that we’re passionate about.

TMS: You’ve won 3 ASCAP Awards in Film And TV Music (2012, 2013, and 2014) for your work on Bones. Aside from these achievements, what do you consider the highlight of your career to date?

Newmann: I would say Bones is still a major highlight, since it’s been quite a bit of my musical life to date so far! Before that, I was orchestrating for James Newton Howard and got the opportunity to work on Michael Clayton, The Great Debaters, and went to Abbey Road to record one of his scores, The Water Horse. Orchestrating for a very prominent and respected composer such as him was such an honor and being at Abbey Road, knowing how many famous people had recorded their music there.

TMS: How would you describe the difference between orchestrating and composing?

Newmann: Orchestrating nowadays is a little different because the composer will mock up the music in their studio quite fully already. The orchestrator’s job is to make the music more friendly and compatible to the orchestra. For example, composers will play a chord on the piano for strings and notate it that way, and the orchestrator really needs to spread it out across the string section and sometimes add or subtract things to make it sound fuller. It’s like a composer giving us a painting that is just kind of sketched, and we’re filling in the colors.

TMS: As is the case in many post-production jobs, women are still in the minority in film and TV music. How do you navigate your industry?

Newmann: When I decided that I wanted to be a composer, I didn’t know that the industry was male-dominated. After seeing Legends Of The Fall, I told my parents that I wanted to be a film composer, and they said, “Okay, it’s not going to be an easy career, but we’ll support you in it and believe in you.” I switched high schools from Beverly Hills High School to the Hamilton Music Academy—that helped prepare me for applying to the USC Film Scoring Program. I think it paid off, just knowing what I wanted to do so young and staying focused on my education and career. I also am lucky in that I’ve worked with people that don’t see gender as an issue and have been very supportive which has helped me move forward with a little more ease.

Also, I’m a part of the Alliance For Women Film Composers, which started about a year ago and is headed by Laura Karpman. The Alliance meetings bring up great ideas of how to get women composers to the next level, through empowering other women and creating “girl clubs” as we call them. We often would complain about the boys’ club thing, and it’s so common to be surrounded by mostly men in the industry like at a recording session and at past jobs with other assistants.

TMS: How do “girl clubs” work?

Newmann: Laura was the one who said, “Let’s start our own girl clubs!” She really inspires me. She has been one of the pioneers in our field and has been successful at it for decades now. She recommended me for a feature film and a couple of short films at the very beginning of my career, and she’s even inspired me about being a mother and composer.

With the girl clubs, we’ll have dinners with other composer ladies. We also carpool to an Alliance meetings, and talk about things about the industry that are so specific to us. We all really understand where the others are coming from, and it’s nice to not feel alone about certain things and about how you feel about certain situations. I’ve also worked with some of my female composer buddies too while hiring them to write on something with me or orchestrate.

The great thing about the organization is that it doesn’t focus too much on the negatives of what’s going on. It encourages us to be proactive and promote change by seeking out other women directors, producers, and executives because women want to help other women. There are more women in more powerful positions than ever before so that’s encouraging to see. That’s what the Alliance wants to focus on, as well as celebrating female composer’s achievements on their website. Debbie Lurie just won the Shirley Walker award from ASCAP last year. The award was started 2 years ago and highlights one woman composer a year who has helped other women in their field with their accomplishments. It’s quite an honor, since Shirley Walker was literally the pioneer female film composer, and an incredible orchestrator as well. We have a long way to go, but at least it’s a possibility to make a life as a woman composer these days.

TMS: If you could collaborate with another woman, who would it be?

Newmann: Gillian Armstrong directed one of my absolute favorite movies in the 90s, the Little Women remake with Winona Ryder. That was the first time I had heard a Thomas Newman score, and the movie touched my heart so deeply. I would love to work on a movie like that with a beautiful setting and wonderful characters, a period piece, even!

There’s also Katheryn Bigelow, who directed Zero Dark Thirty. She’s done some other controversial films and did a PSA called “Last Days” about the poaching crisis with elephants for their ivory. I really like that she is raising awareness with her filmmaking. One of the many things that I do outside of TV and film work is working

with the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust that saves baby elephants that have lost their families to poaching. They do online films about their rescues and other ways they’re helping their communities raise awareness about saving the species. Cody and I donate our music to them to raise empathy for elephants with music, and it feels so great to be doing something for the world with music, other than entertainment. I’d love to work with more directors that are interested in activism.

TMS: Lastly, any advice for women looking to get into your field?

Newmann: The best advice is to stay focused. I didn’t really go on too many tangents when I graduated school. I stayed true to my goal and I feel like that accelerated things for me. Also, get a good education. I certainly can tell the difference between someone who has had formal training and who hasn’t. I really think the USC program for music composition has been very helpful to me in accumulating musical tricks and understanding how music is put together and how the orchestra works. The ASCAP Film Scoring Workshop was also pivotal to my start as I made some very important contacts there that are still helping me in my career now not to mention getting a kick ass recording of my music with the best musicians in the world.

Don’t get discouraged that there isn’t an equal balance of men to women composers. It can be an advantage because you are more easily remembered and there are men in this industry, especially in younger generations that are either climbing the ladder or are already established that really don’t see it as an issue. Remain professional and have confidence that your music will also speak for itself.

As far as work-life balance, I’ve definitely gained a lot of confidence talking to other female composers who are working and kicking butt and are also mothers. I’ve talked to several women at different ages, and they all say the same thing: having children will make you more efficient. They even say that their careers flourished after having children. There’s maybe more of a drive, because you know that you’re not just doing it for yourself anymore. I really like that, and I find it empowering. Cody and I are expecting a daughter in April, and that’s how I’m going to do it after she’s born!

Jaimie Li received her law degree from Balliol College, Oxford University and works in music and film law. When she’s not drafting contracts, she moonlights as a writer and illustrates at dawn. She is currently flying solo on a 6 month road trip across the US and might be coming to a town near you! Check out her blog http://smallbraveries.net and follow her on Instagram @jaimieli1.

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]

![[brief pic description]](https://www.themarysue.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/download-40.jpg?resize=271%2C186)