Though 2020 was a year of heaviness, it was also a year of powerful Black creativity. From music and Film/TV to (of course) books, the abundance of work that emerged this year beautifully illustrated the nuances of the Black experience, while also making important social commentary on the shortcomings that still need to be confronted.

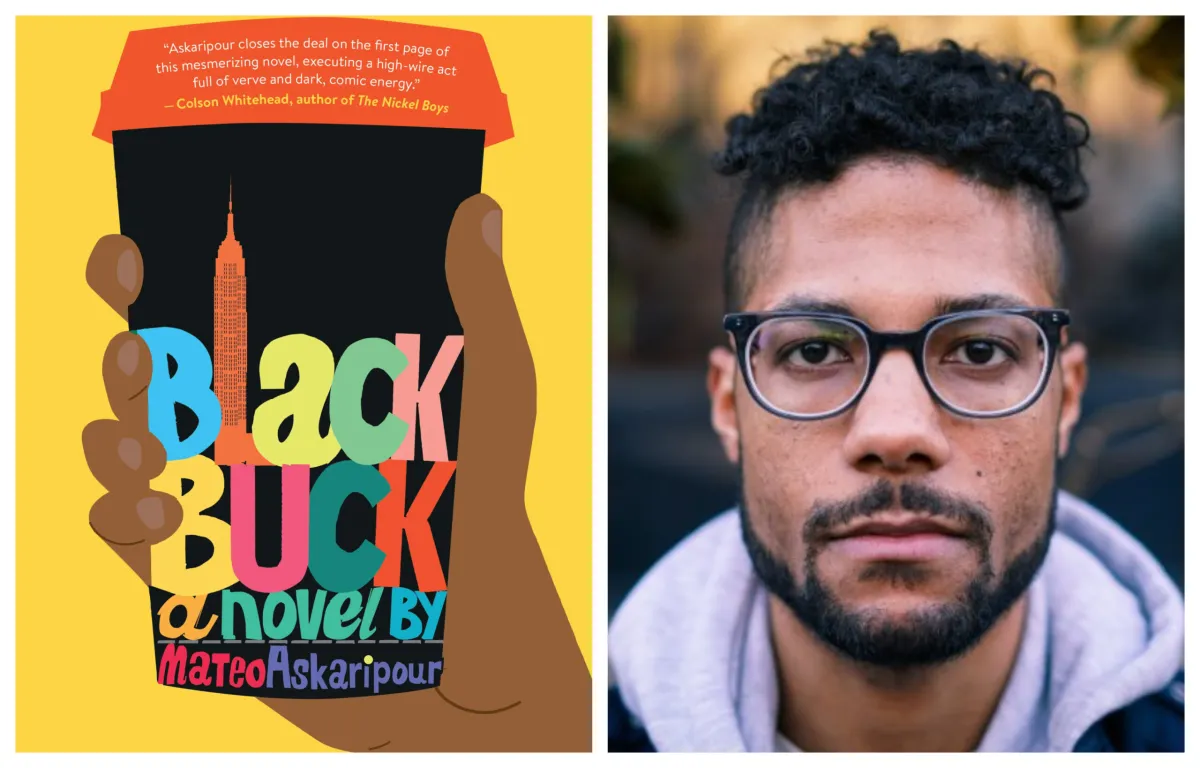

Black Buck by Mateo Askaripour is one of those works, having already made a splash even before its official January 2021 publication date. Beautifully marrying the surrealism of Sorry to Bother You with the outlandish escapades of The Wolf of Wall Street, Black Buck is gearing up to be one of those novels that will definitely spur important, long-standing conversations.

The Mary Sue got the chance to chat with Mateo about his newest novel and the spark that ignited the inspiration for this story. Check out the exclusive interview below!

The Mary Sue: What inspired you to write Black Buck?

Mateo Askaripour: There’s a handful of things. One was just like necessity. You know, talking about my own creative career, I wasn’t where I wanted to be as a writer. I had left the world of tech startup and writing for me—before I even thought about it being a career—was an outlet.

So I began writing a novel while I was still working at this company, just as a way of getting out of my head and feel excited again. And soon after that, I was like, “Wow, I’m really losing myself—in a good way! And [during] the writing process, time was almost ceasing to exist because I was so in flow.

I like myself so much better when I’m writing. I’m fulfilling this creative side that I felt had gone dormant for so many years, in certain ways. So when I left the tech startup, I said, I want to I want to go all in on this.

And it was 2016 when I became a permanent [full-time] writer—but flash forward to about two years, and nothing had happened. I’d written two manuscripts, but had no agent, nothing published. I’d definitely grown as a writer, but I still wasn’t where I wanted to be.

So, sometimes when you’re pushed past your breaking point and you get into “f*ck it” mode. And I entered f*ck it mode, and Black Buck is where I ended up. It was a novel that was born out of a place where I told myself, “I’m going to write what I want, how I want it, and for the people I want it to resonate with the most.”

TMS: That makes sense. And I really get that through the book too. Especially from the very first page, there’s this beautiful rawness where it feels like you as an author are saying “I’m speaking to exactly who I’m speaking to. If other people get it, that’s cool, but this if for you.” And I really love that, because essentially—

Askaripour: You’re along for the ride.

TMS: Exactly. And you know, sometimes our experiences as Black people really can feel like being in the Twilight Zone or The Truman Show. Very surreal, and almost satirical. And so I think it’s beautiful that you use satire as a way to tell this story. Why do you think satire was the best lens for this novel?

Askaripour: Yeah! To be honest, it wasn’t a conscious decision. I didn’t set out saying that I was going to write satire. I set out knowing that I wanted to write something that felt true, that highlighted the horrors or racism—but that would also be underscored by humor, because that’s the way I am. Not to say humor is my default: I do get angry, and I do get upset. You get emotional about everything that’s going on in this country, and that has been going on historically.

But what I found to be one of my greatest superpowers is being able to stay loose in the fight. To be right—but not be too rigid. And this book was something where I imprinted my mind onto it; one page you could be holding your stomach from laughter—or at least I hope so—and then two pages later, you want to punch the wall. That is the way I am, but not in a manic sense. Day to day, this is what it’s like, in my experience, to be a Black person in America. And I think it was [James] Baldwin that said that “to be Black in America is to be in a constant state of rage”.

But that’s not how I am all the time. I need to embody a certain level of ability in myself that prevents me from getting sucked under the immense and constant wave of what is happening to us in this country and in the world.

But to go back to your question, as I was writing Black Buck—and especially afterwards—I did begin to understand that the book contained many satirical elements. Which I pushed back from at first. Because back then I thought “satire? Isn’t that just close to absurdity?” But as I understood that satire more through the lens of storytelling, I realized just how powerful it was. It is the intersection of tragedy and humor in order to tell and reveal truths about the world.

And so am I, you know, eager to just drop the book into the bracket of satire? No. But I definitely do recognize and welcome the trickle of elements in it. It brings to mind the episode of SNL Dave Chapelle hosted a few weeks ago where he said. “Listen, it’s unfortunate, but I can’t tell the truth without there being a punch line.”

And that that really resonated with me, because while Black Buck is first and foremost for Black people, I think we also need to be given the space to laugh, and just smile, not at the sake of tragedy. But amongst it.

TMS: You know, that brings to mind this statement I heard repeatedly through the year, which is that “Black Joy Is Revolutionary”.

Askaripour: Exactly right! The point I want to make specifically in terms of Black joy being revolutionary, is that it’s also very tough. Because sometimes when you’re smiling, it’s like you’re smiling in the middle of a hurricane. And as a Black person specifically, sometimes your joy can be misconstrued as not caring. You can have other Black people—or even non-Black people—say “what’s wrong with you? Wow, you’re really not being affected by this like I am, because I can’t breathe right now. I can’t function, I can’t work. There must be something wrong with you, because you clearly don’t care.”

And then you begin to confront that question: Is there something wrong with me? Do I actually not care as much as I should? Because I do feel bad—but I can still manage to work and write. I think there’s just complexities to this subject, there’s so many levels.

TMS: And I think it’s almost a catch 22 sometimes because it’s like “damned if you do, damned if you don’t”. I believe there just needs to be room to hold space for all the nuances of how Black people process and embody their unique but shared lived experiences.

Askaripour: I completely agree.

TMS: Which feeds into my next question. I loved how Black Buck kind of served as a double meaning. It’s the monikor that Darren adopts after getting into Sumwun [the tech start-up]—but it also makes me think of Black money and the spending power that the Black community embodies. Was the title a metaphor for the code-switching and double realities that Black people tend to embody in this society?

Askaripour: I’m happy that you picked up on the meanings of BLACK BUCK! There’s actually four meanings: So there’s Black money as you said. There is the name that Darren assumes when he joins the start-up. There is the historical connotation of a Black Buck, which, as you may know, was the name of an unruly, untameable slave that white masters feared was going to burn down their plantation and steal their women. And then there is, of course, the fact that Darren worked at a Starbucks [in the beginning of the novel].

It’s funny, some people pushed back on the title of this novel and called it into question because they were like “yo, you buggin’. I feel uncomfortable saying Black Buck because there’s a connotation about it”.

But for me, as I thought more about it, being a Black Buck is entirely what Darren is doing. He’s going into this system from the inside out—and not exactly burning it down, but becoming unruly and re-imagining what it means to be a minority in the workplace, and how these businesses function. And who knows if the change is long-lasting—at least in the world of the book, right?

To answer your question directly, I think it’s about survival. Right? There are some Black people who go into these all white spaces, or they have their all white friend groups. And they don’t act the same way as they would with people of their same race, or even their families—out of survival.

Because in some ways, you could be opening yourself up to unwanted vulnerability. And that’s when people have the potential to get hurt. And what I thought about in terms of Darren, and the whole code switching and being another person.

And the more I think about it, you don’t always want to show every part of yourself to all different types of people. They don’t always deserve those parts of you. I speak with my brothers in a different way than I speak with some Black friends. And I speak with my mother in a different a way than I speak with white people professionally and Black people professionally, etc. There’s so many levels and degrees to it. And some people can look at that and say “you’re brainwashed, you’ve got to keep it 100 at all times with all people.”

But my gut reaction is that not all people have earned the right to me unabashed. And it’s also not who I am 24/7, I’m constantly shifting—it’s just the way my mind works. And the final thing I would say is that all people want to negotiate different iterations of themselves in different places. For some people it’s easier, for others it’s harder to just be who they are all the time. There’s no inherent right way, and I would never hold someone up to unrealistic expectations of how they embody that. All that matters to me is being able to hold space for yourself in a way that doesn’t come at the expense of others.

TMS: Yeah. And that being said, I know, personally, writing has been one of the most powerful outlets for kind of navigating these things, and putting to words some of the bigger emotions/thoughts that I can’t necessarily just confront on my own in the moment. How is your personal writing process? What was it like when you wrote Black Buck, and do you think it’s changed at all?

Askaripour: When I was first writing Black Buck, I was having the best time of my life. I was having so much fun. And not fun always in the sense of like, “woo-hoo!”, but fun in the sense that it just felt right. And I was being super playful. And I allowed myself to feel everything that these characters were feeling. I had to, in order for the characters to feel and then for the reader to understand what was going on.

And there were times I was laughing, there were times when I was talking to myself saying, “Bro, you’re wild and right now this is crazy, you might be going too far.” And then there were other times when I was sad. And I had tears, because, you know, it was not easy for me to write certain things in the book, right?

But man, it was, it was the greatest time of my life.

What’s changed now, is that it takes a little bit more effort for me to get into that headspace. Because there are so many other eyes on me now, especially because of this book. I’m so fortunate to be where I’m sitting, because people believe in this book, people are backing it, and it’s hopefully going to resonate deeply.

But because of that, it’s a catch 22 because I have a lot more eyes on me, and the stakes are higher not just for myself, but for so many other people. And with that in mind, it takes a little bit more effort to be in that “f*ck it!” state that I was in when I was first writing this. I’m in a new scenario, and I have a lot more people looking at me for good, for better, or for worse. And it just takes a little bit more for me now to get in that scenario where it’s just me and the work. But I’m grateful for the opportunity, and the way in which my writing and my writing headspace have evolved. I do have to be even more protective of my creativity. But it’s part of the journey, and we’ll see where it takes me.

—

(via, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Published: Dec 21, 2020 12:34 pm