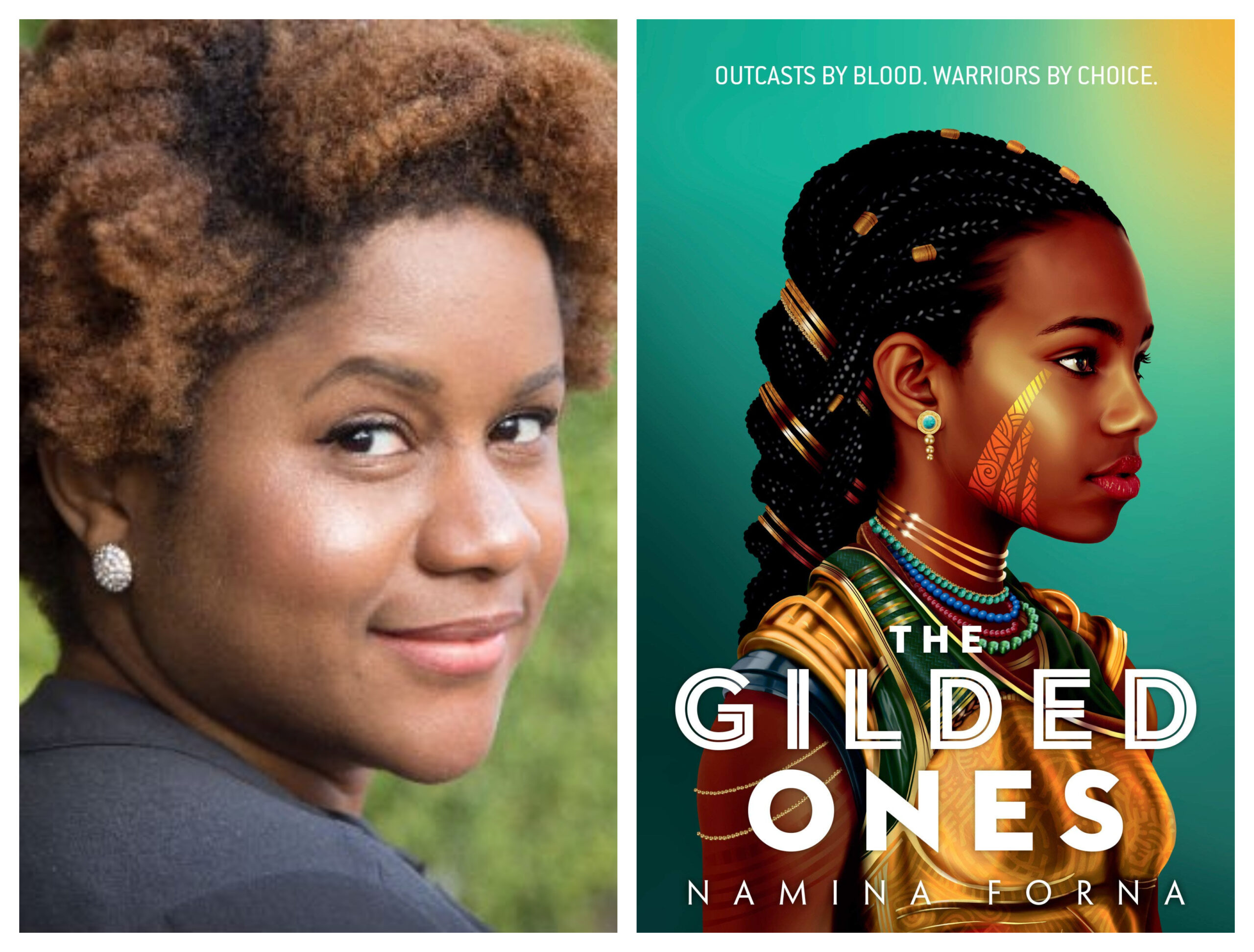

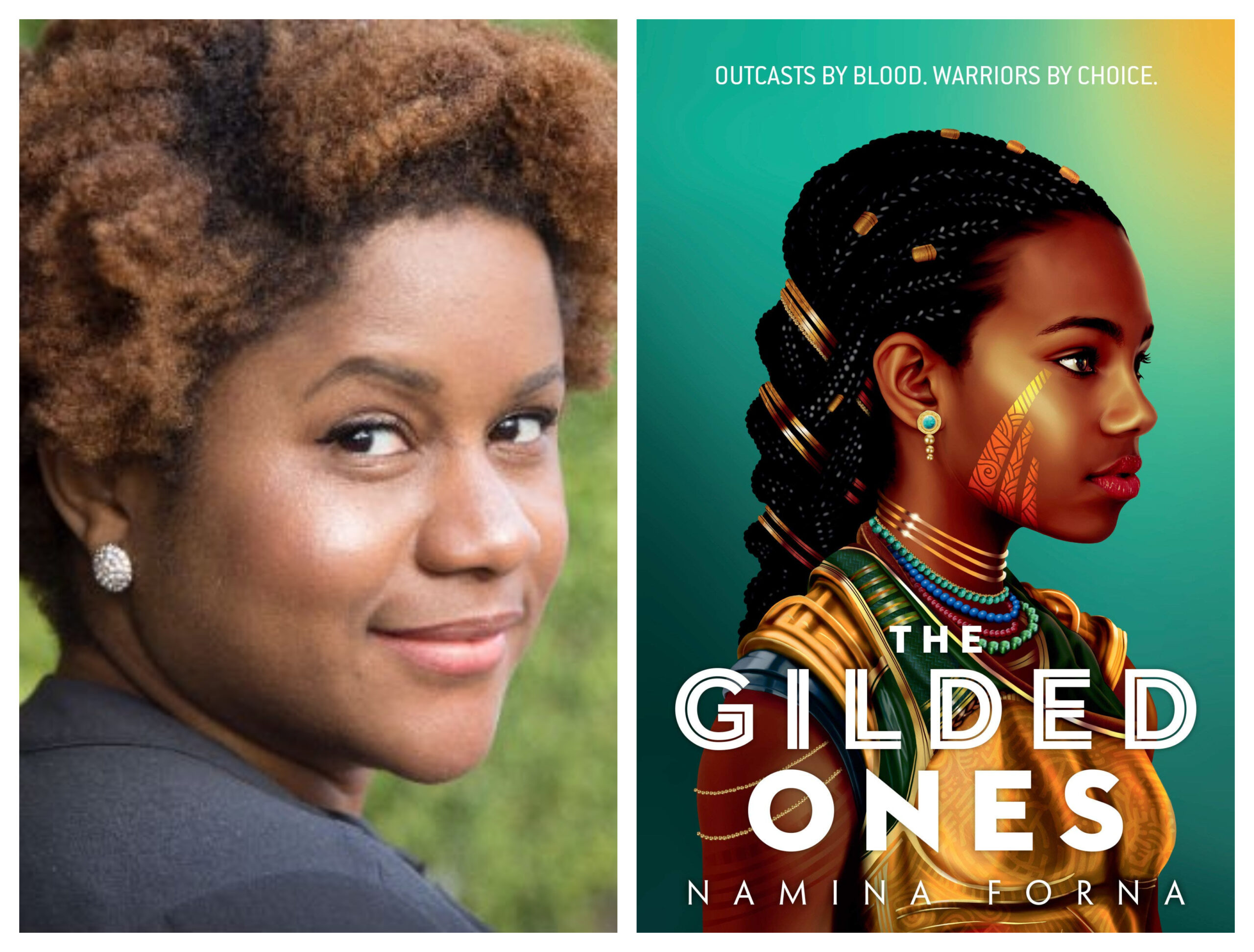

INTERVIEW: Namina Forna on Her Highly-Anticipated Debut YA Fantasy Novel, The Gilded Ones

YA Fantasy has for the past few years been experiencing a beautiful Renaissance of diverse, imaginative, and truly groundbreaking stories. What I’ve found so beautiful about this evolution of storytelling is the number of readers, both young and old, who have been able to see themselves centered at the core of the story for the first time. It’s a truly notable thing, because as we’ve said time and time again, representation matters. And these stories and books only continue to open wide the door for others to share their perspectives, and see themselves as the hero.

Namina Forna is one such author whose debut novel, The Gilded Ones, has been a highly anticipated read (both on my personal reading list, and in the larger booksphere) for about 2 years. A feminist fantasy steeped in African mythology, The Gilded Ones follows Deka, a teenage girl who finds her life changed in unimaginable ways when, during a blood ceremony for acceptance into her village, her blood runs gold, and she is ostracized from her village—but given new life as an Alaki, a near-immortal warrior for the Emperor.

The Mary Sue got the wonderful chance to chat with Namina about The Gilded Ones, her writing journey, and the beautiful thread of hope that runs through the “book of her rage”.

Check out the interview below!

Firstly: congrats on The Gilded Ones publishing! How have you been feeling about everything?

I’m honestly like on cloud nine. Is that the expression? I’m on cloud nine. I’m so happy and excited with the way that things have been going. And after this long journey, it’s more like a sense of relief. I was also like “Trump didn’t ruin my day!” [re: the capital riots & impeachment] because I was worried about that too, you know. I’m just happy!

What first sparked your inspiration to become a writer?

I think I’ve always been a writerly person. When I was a kid, I was the type who would read, like, all the time, every day. And I would read like eight books a week, every single week. I always had my nose in a book. And you know, I grew up in Sierra Leone, and I grew up during the civil war, so reading was my escape. It was just the way that I got away [from everything]. And so when I was growing older and trying to decide what to do, I realized: I have all these stories in my head. I could either be crazy, or I could be a writer. And I just decided.

You mention growing up in Sierra Leone during an unimaginably difficult time. How did your upbringing inform your writing and how you saw the world?

I think I grew up with an expectation of violence. And what I mean by that, is that violence was always sort of there — but I was shielded from it. But that didn’t mean I didn’t see things out the corner of my eye, or that I didn’t have an understanding. Because when things are happening to your family members, you hear it, you know it, you see it, and you feel it in your bones. So I grew up very fearful, and always grew up with that understanding of the evil that people can do.

I think that in the United States, things are sanitized. People are like “Oh my gosh, it could never happen!” But I’m like “it’s happening next door.” Just because you don’t like what they are doing, doesn’t mean they aren’t doing it, you know? And for me, I grew up with that violence sort of in my face, and even though my parents did such a good job of protecting me and shielding me…there’s only so much you can shield a person from.

And you know, people say The Gilded Ones is a brutal book. And I’m like “yes, because that is reality.” On the outside, it is a fantasy world. But it is also a dystopian world, because this is a book about violence against women — especially Black and Brown women, these sorts of issues we’re all very aware of. And for me, if there were actual Alaki that lived in this world, these things that I wrote in my book would happen, I have no doubt.

And that is what I put into the book, this understanding that, “hey, we live in certain systems”. As a Black woman you understand, we live in systems. And I wanted to create a world that showed what such a system would look like; how people would behave.

And sometimes readers are like “you know, why was Deka [the protagonist] so docile in the beginning?” And well, she’s docile because when you grow up indoctrinated in a system that forces you to be so, it only makes sense. And as she grows up, she realizes that it’s only now that she’s able to find her voice.

And that’s why there’s a theme in my work of finding your voice, because it was such a personal struggle for me to unlearn what I’d grown up learning. But in addition, I also had to learn how to assert myself and take up space in the world. And I think that’s a thing that women, especially Black and Brown women, have to learn; it’s a process that we have to embody, because everything is so geared to ensure that we never learn to take up space. And like I always say, The Gilded Ones is the book of my rage.

I’ve called this current period of time a sort of renaissance of diverse stories, especially in science-fiction and fantasy. But unfortunately, it wasn’t always that way, and there’s still a long way to go. What was your own writing journey like?

The [publishing] environment when I started writing felt impossible as a Black person. Because when I started, I’d just written my first novel as an undergrad at Spelman College, and I’d begun querying. But I think the moment people saw the name Namina, they immediately saw foreigner, and I wouldn’t even get a response. I’m sending all these queries out and there would be whispers where people would be like “you know Black books don’t sell, etc.”.

And I think this is my privilege as an African, because I think being African insulates you from a larger understanding of American racism. Because I’m African, born and raised, I came from a place where everybody was Black. And therefore, everyone could do it, because you know, things like [race] weren’t a factor. I came to the US when I was nine, and these weren’t things my family was steeped in. We just didn’t have the same understanding of it. And so I ended up having to go through that process of learning and understanding just what American racism was. And that was such a shock to my system. Because you know, coming from the outside of [the US], we believe in the myth of American merit. The “as long as you are good, as long as you try your very best, you can do it.” But unfortunately that was indeed not the case.

And so that was a bit of a horrifying time for me, because when I really sat down and looked at my querying journey and realized what exactly was happening, I fell into a deep depression. Because it was like “Oh my gosh, is this really the world that I live in?” Because I had no idea. I’d had all the language for it because I went to Spelman. I had the education for it. But having all of that versus having an actual lived experience is a very different thing.

I also went to film school, and one of the things you do at the end after going through the writing track is an exhibition where you showcase your work, and pitch it to a selection of agents and managers. And I remember one of the worst experiences was sitting there with this agent, and having them tell me “you know, your ideas are solid, but nobody’s gonna buy it. Because this isn’t what the industry is looking for right now.”

And I’m confused and go “what do you mean?” And they were like “Nobody wants to buy Black stuff like that. It’s not what’s selling. It’s not what’s hot.” And that was devastating. Because here I am doing the struggling artist thing, doing everything I can to get this dream a reality… why wasn’t it good enough? It made me feel in that moment that it didn’t matter how good you were. All that mattered was your skin color and your gender. And the fact that I was a Black woman? Nobody would give me a chance.

And so you know, thank God for people like Dhonielle Clayton, thank God for Angie Thomas. Thank God for Black Panther and Get Out, because if it hadn’t been for those works, I would have never had a career.

I’m really sorry you went through that. It’s unbelievably frustrating the ways these barriers of accessibility have been put in place.

And it’s so so, so harmful. Because people really don’t understand the power of stories: they can shape minds, they can shape cultures, and they can have a ripple effect in shaping society as a whole. So if you always put out this certain default of whiteness being the “normal”, and not wanting anything else, it creates this harm — and honestly trauma — that’s perpetuated between people.

It becomes this thing where it’s like, I can’t see myself as the hero of a story because I never saw myself in the first place. You know what I mean? And then we end up internalizing the idea that we’re not enough. That we don’t deserve to be the heroes of our own stories. And that is the danger of having only one narrative.

What advice would you give to young Black writers now who are just beginning their writing journey?

Find their community. Find a writing community. If you’re a teenager, I don’t quite know how I feel about recommending Twitter, so maybe less of that. But overall, find your writing community, and find other people who can develop with you and help you on your journey. I’m here as a writer today because a whole community of people gave me the space to write, and that’s so important. As a writer, you need that space, and you also need that mental capacity to do it. Someone who will listen to my stories, give me advice, write their own stories alongside me. A writer needs to speak to people, and they need a person who absolutely supports and believes in them.

That’s so important, because for many years, I did not have that. And that makes all the difference. Because this is the thing: as long as you have the stories, you can technically get there in terms of writing, right? Like the actual writing skill itself doesn’t matter as much as the community that helps get it to where it needs to be. I like to say you have to practice your writing to earn the stories that you get to write. So having a person, community, and critique partners who believe in you and help you get to that point is so crucial.

The other advice I would say, is get a solid day job. That was my problem, I couldn’t ever find a solid day job. Of course I got one eventually — but it took a long time and a long strong, and I was perpetually poor. So having a solid foundation takes some of the pressures of writing off you a bit.

The third advice I would give is to recognize that writing is a marathon, not a sprint. People who are overnight successes are never really overnight successes, because they probably wrote six or seven books before that. The first book that they sold, that became successful, is not the very first book they ever wrote.

So just recognize that, you will get there. It may take you a little longer than you want it, but in the meantime, enjoy the process. Enjoy what you’re doing, find your community, and find tools to help build yourself up to there, because you will get there.

What does your writing process look like? Are you a pantser or plotter?

I think all writers start off as pantsers because it’s instinctual. And I definitely started as one personally. But going to film school trained me to be a plotter. So I have a very specific process now: typically, I get a book idea from a dream, or just a thought. And then I’m like “Huh, this is really cool.” So I call a couple of friends, and we talk it over. And then I sort of craft and shape it and build it from there. Afterwards, I realize “okay, this is a feasible, plausible idea” and I set it down. And I go about my business.

And following that, I do what I call “passive research”, which is usually for a year, I’m just watching movies or documentaries, or what have you, that are related to this thing. And sort of tangentially getting my idea from those resources, but not forcing anything. So what happens usually afterwards is like, a year or so after this passive research, I find myself sitting down watching a movie or some TV — and the idea will come to me again. But this time, fully formed.

So at that point, I will again call up my friend and we’ll talk it over together to polish and shape it. (Also by friends, I mean critique partners). And then from there, I write the outline. And my outlines are usually about six to seven pages long. Which is really detailed, but not because I don’t feel like there’s always room to discover things. After a certain point when you’re writing, the characters start talking to you. And sometimes they go off in tangents that you don’t know, paths that follow the general shape of the story. But even in those moments of discovery, the characters are still guiding you along the way.

So I sit down and I start writing. Typically, if I’m really sort of in my space, I wake up at 4 or 5AM to write, as those are my prime writing hours. Then I stop around 10 to eat breakfast and do my stuff. And then you know, continue on with my day.

I love how large of a role your critique partners play in your writing process. And I love the advice you gave earlier about young writers finding a community. How important do you think it is to have that kind of support around you as a writer?

It is of the upmost importance. You are only as good as your critique partners. Like I think a lot of times people think that writing is a thing of solitude, that you’re off in a corner, etc. But no, that’s not the case. My critique partner, PJ, we talk for an hour every day, and we check up on each other and make sure that we’re each on schedule, you know? Because that’s the other important thing: accountability. Because some days she’ll call me and be like “what are you doing, where are your pages you promised for Monday?” and she’ll make sure to snatch me back on track.

So it’s really important to have critique partners. PJ’s my primary, but I have multiple critique partners for different things. I have one friend, for example, who’s amazing at story. And so when I have an idea, I’ll run it past her and she’ll help me shape it. And PJ has a talent for handling emotion, which is helpful for me because when I first write a book, I have to get it all down and then pencil in the emotion. So with all these different skills between these different critique partners, we balance each other out. So again, you’re only as good as your critique partners, and you need multiple.

Great advice! Especially since there’s this misconception is that once the book is published, the process stops there. But you would say it’s always a continuing journey of strengthening your craft and having those people around you to nurture those ideas and strive to do better, right?

Oh, yeah! Like my writing has leveled up since writing The Gilded Ones. I’m not the same writer now that I was when I wrote that book three years ago. My writing has gone through so many evolutions; the notes I received back then are not the notes that I need to hear now.

And that’s the best thing about writing, is that you’re always striving to do better. And that’s also what makes it so exciting, because you’re always becoming a better writer — or at least trying to do so.

What’s been the most surprising thing in your writing process and/or writing journey?

So the other day, I was doing a meditation because I couldn’t sleep. And on one of the Youtube videos I’d chosen, there was this image of this person who is sitting down, and there’s a light pouring into their head, and it’s coming out. And that’s what it feels like when I’m writing. For me, writing is deeply spiritual. Like when I’m in flow state, it’s almost like I’m tapped into something else that’s just not through my fingers.

And I called my friends, Melanie, and was like “what is this?” And she’s like ” Oh that’s when your heart, mind and body are in full connection.” So that was the minute I understood why I love to write so much. Because when you are in that flow state, you are there.

It’s almost like you’re tapping into the Divine. That’s what it feels like. Because sometimes, I feel like the stories [I’m writing] come from different places. And we as writers, I think our skill lies in taking so many different things and putting them together and making them into something coherent. And that to me is just magic. It is the magic of writing.

Beautiful. What stories are you most excited to write in the future?

Okay, so I have this one story that I’m so infatuated with. Because I’ve always wanted to write a female character who’s sort of an asshole who goes through a whole storyline of redemption. I also have been super excited to explore the mermaid worlds that have been brewing up in my mind. I have so many different worlds I want to bring to life, and that’s really all I want to do. I just want to create massive, amazing, fantastical fantasy worlds.

And I think right now we also need things that are warm and fuzzy, that you can find support in. Those are the natural worlds I want to create. I always say that The Gilded Ones is the book of my rage, because it is. But now I also want to create books of my heart, and books that make people feel safe and nurtured and comforted.

Do you have any authors or any writers that have inspired you?

I’ll definitely say Dhonielle Clayton, because when The Belles came out, I had never seen [ that type of story featuring a Black protagonist]. And it’s so funny because I know her in real life, but I don’t think she knows to the extent that she inspires me. I also look up to Angie Thomas, because she opened up those doors for us.

And you know also, as an aside, there are so many things that we make comparisons to. But for me, how I judge whether a book is successful or not is if I get a note from a reader that says to me, “I loved this book.” I’m waiting for someone to come to me with a book that is water stained. That is falling apart, because then I know that that’s a book that has been loved and read multiple times.

After that, the rest of the stuff doesn’t matter. Because at the end of the day, I write in service for other people, that is my act of service that I do. And for a person, especially a young person, to find solace in my work? That means I’ve done my job. And that’s the metric I judge myself.

Last question: If you could describe The Gilded Ones in one word, what would it be?

Golden.

Because for all the pain [in the book], for all the brutality, there is gold in it. Especially in how the women relate to each other. I think that for girls especially, there is a tether, a thread that ties us all together. And that’s what I hope that people will find in this book: the gold of our relationships.

(image via Delacorte)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]