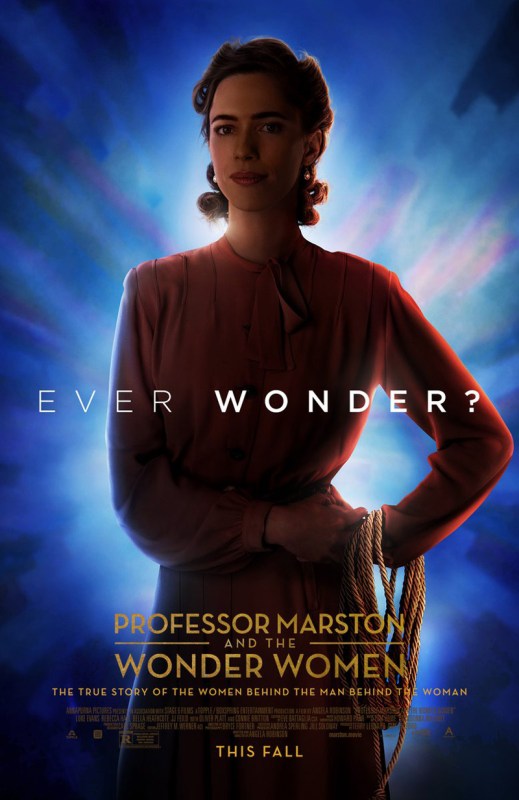

Interview: Rebecca Hall Praises Professor Marston As a “Traditional, Romantic Movie About Un-Traditional People”

I’ve been talking up Professor Marston and the Wonder Women a lot around here, because I happen to think it’s a beautiful and important film. The perfect casting has a lot to do with its success, and I’ve been lucky enough to have a chance to speak with all three of its leads as part of my coverage. Earlier this week, I spoke with the supremely talented Rebecca Hall, who plays Elizabeth Marston, and she had a lot to say about why she believes Professor Marston is so important.

Hall, whom you might know from her work in The Prestige, Vicky Cristina Barcelona, and Iron Man 3 among other things, has yet to see the film with an audience, as she was unfortunately unable to attend the world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival. However, when the film comes out this weekend, keep your eyes peeled in your theater, as Hall says, “I might even try to sneak in on the weekend with some friends.”

I asked her what the response has been so far as she’s been doing press for the film, and she’s been happy to discover that a lot of people have been grateful for the portrayal of this particular relationship in all its polyamorous and kinky glory.

“Also, it’s a film full of a lot of hope and good feeling toward the whole endeavor of Wonder Woman and what she represents,” she says. “I think that is a welcome film right now, a film that roots her in her pacifist, feminist origins and talks about a group of people who were idealistic and hopeful and trying to make the world better, and who against all the odds lived their truth. It’s really resonant and wanted right now. There’s a real desire for a film like this.”

Hall was interested in the Marstons’ story long before she was approached about this film, having read Jill Lepore’s book, The Secret History of Wonder Woman. She found herself intrigued by the story enough to do more research into it, and at one point she wanted to produce a film telling the story herself. That ended up not happening, but it was through that process that she came to Angela Robinson’s script, which Robinson had been working on writing and producing for eight years.

“When I read her script, I was really astounded by her interpretation of the Marstons,” says Hall. “Because I’d spent time thinking about it, and thinking how is it even possible to weave all of the broad and sprawling elements of these extraordinary people’s lives into a film? And also, how do you make the film that we need now? How do we make the film that is going to be the most positive now? It would’ve been very easy to make the film that is, you know, salacious. Or, for want of a better phrase, ‘male-gazey?’ And I think there are many many ways for us to incorporate the facts that we have about the Marstons. There are some facts that we know, and there are some facts that we don’t. Which is the case for any group of people who’ve led hidden, secret lives. When I read Angela’s script, I just thought this is it. This is the interpretation that is pure and hopeful and sex-positive and correct for now.”

Hall goes on to describe why the role of Elizabeth Marston in this film was so irresistible to her:

“I loved [Robinson’s] Elizabeth. And that’s really her. It’s difficult to say who Elizabeth Marston really was, but Angela’s reading is of this woman who owes as much to 1930s heroines of screwball comedies as it does to what real Elizabeth Marston might be like.

And she’s got this fantastic human contradiction. She has this public persona which is contrary, and avant-garde, and daring, and fearless, and she has the inner, which is full of fear imposed by the context of her upbringing in this society, and full of shame around what her truth is. and the journey of the film is, in many ways, her working out how to be true to herself, and to be vulnerable to love. That’s something we can all relate to, whatever we think of polyamory, or Wonder Woman, or whatever it is. That is a very relatable journey, and I found that very moving.”

One of the things that Hall loves most about the film is that it is, at its core, just a standard romance. The very thing that makes it what some reviewers refer to as “safe” is exactly the point.

“Angela set out to make the traditional, Hollywood romantic movie about untraditional people that doesn’t exist,” Hall explains. “And she does it. You’re really swept along by the romance of it. There’s all these sort of romantic tropes in the film that root it in this tradition of classic Hollywood romance. Yet, it’s about people who traditionally in depictions in movies have not been portrayed in a positive way.”

I brought up the fact that several reviewers have thought that the film “plays it safe,” which makes me laugh, because the film features nudity, kink, sex, and polyamory. All the elements are there. And here are people worrying that they aren’t feeling scandalized or having their boundaries pushed hard enough. Perhaps there’s a reason for that.

“[They’re] not seeing that it’s working,” Hall says. “You’ve been tricked in that sense.”

Hall also has a problem with the notion that this film “should’ve” told the Marston story a different way, which has come up as she’s been discussing the film with the press and the public. She says:

“It almost feels like a misogyny in itself to suggest that the only real telling of this story should be that the women were somehow victimized, or tricked into doing it and had no autonomy. That’s come up a little bit, and I think why do we need to tell the patriarchal version of this? How about we tell the one where the women are empowered by this, and they decide to do it, and they’re complicit, and all of these characters are involved in a consensual relationship? Again, this is something we don’t see very often. We see the other thing all the time.”

I asked her if there was anything about her research, or making the film, that surprised her or confounded her expectations about sex, or gender politics, or relationships, and she said no.

“I love people in all their various shades and everything they get up to,” she says. “Nothing really challenged me, I just believed in these people and I believed in their love. And I also believed in the purity of it. There’s something quite naive and pure about these characters, that they’re all coming to this and discovering their sexuality in quite natural, organic ways, and that feels much more eroticized than ‘How can we look sexy for a movie?'”

Hall hopes that people take away a sense of hope and optimism after seeing the film. She also hopes that people are “challenged without really thinking that they’re challenged. There’ll be a fair amount of people who go into this film expecting one thing, and come out just rooting for people and not thinking that there’s anything strange in rooting for them.”

I’m sure that if you see this film, you’ll be rooting for the Marstons, too.

Professor Marston and the Wonder Women arrives in theaters on FRIDAY.

(image: Annapurna Pictures)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]