On the surface, the CW’s new show iZombie is nothing out of the ordinary. It’s simply another example of the their move from teen drama to embrace all things genre.

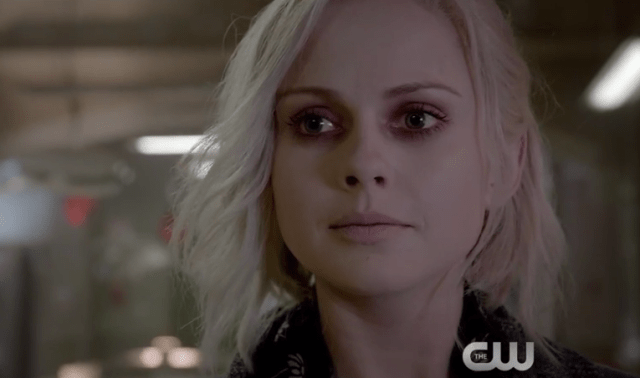

Open on Liv Moore, a happy young woman who has it all. She’s a doctor, happily affianced, her co-workers love her. She saves lives.

Unfortunately she gets mauled by a Zombie. This gives her the need for brains. She quits her job and starts working at the morgue. She has to feed regularly or turn into the standard Romero-esque zombie. When she eats a brain, she see’s things the dead saw. She uses this power to solve crimes.

Fun little set up for a series, if you’re into that sort of thing. (I so totally am.)

But take all things explicitly zombie out of the formula, and you realize that Liv Moore’s story is the same story thousands of women experience every year. Liv is a coded survivor of sexual assault.

Zombies are generally portrayed as faceless monsters lurching at us from alleyways. This matches the rapist construct that persisted and still persists. The conventional wisdom asserted that rapes happen in dark alleys, and are perpetuated by monsters.

Slowly as a culture we have come to recognize that most rapes happen in far different circumstances. They happen on dates, in cars, and at parties.

This changing cultural perception is mirrored in iZombie’s changing presentation of zombieness, and of Liv’s infection.

Liv isn’t attacked by a faceless monster in an alley, she is assaulted at a party. And while she is technically attacked by a monster, he’s a good looking monster with nice clothes and white teeth.

What caused the initial zombie outbreak in this world is yet to really be defined, but early clues suggest a street drug called Utopium.

Liv is offered this drug at the party, by a good looking dealer. She declines, and the dealer slaps her ass as she walks away.

This moment right here says everything. She is offered drugs that could well incapacitate her or muddy her thinking. And this man, this good looking well dressed white man, feels like he has the right to her body even though she has clearly rebuffed him.

Later when the party gets Romero, Liv is ipso facto “given” the drug through a zombie scratch.

And of course the zombie who attacks her is the dealer.

The reference to the role that drugs and alcohol play in many assaults couldn’t be any clearer.

Quickly after the opening scene and the assault at the party we cut to six months later. Liv has drastically changed her life.

She’s quit her job and dumped her fiancé. She’s pale and withdrawn.

The show can be painfully on the nose with survivor cliches. Liv is literally pale. Because she’s a zombie. She feels like she can’t touch or kiss her fiancé. Because she might turn him into a zombie.

It could almost be insulting. As could the reinforcement of the “rape as origin story/super power” trope that pops up in pop culture from time to time.

Liv could turn out to be a source of strength for a group that is often misrepresented or ignored in pop culture, or just another humiliating caricature. It will depend how human Liv turns out to be.

As interesting as an intersectional reading of iZombie is, it gets even more interesting when we consider the other projects that the producers have worked on.

iZombie was created for TV by Rob Thomas and producing partner Diane Ruggiero. The team first hit it big with Veronica Mars, a show about a girl detective who was an actual, no beating around the bush, survivor of sexual assault.

So iZombie’s coded representation of survivors could be one of two things: a sad step backward, or a savvy sidestep from creators who want to have their brains and eat them too.

For its first two season Veronica Mars was a sleeper hit for CW precursor UPN. The critics loved it and it inspired a fanatic fan base. In its third season UPN and the WB voltroned into the CW. Veronica Mars stayed through the change, but was cancelled after one more season.

A decade later it was revived as a fan-funded movie that broke Kickstarter records, raising $5,702,153.

That’s by no means a failure, but it’s also not a grand slam. Are Thomas and Ruggiero more timid this time around?

iZombie is based on a comic of the same name, but beyond the sentient zombie who must eat brains to stay reasonable, and the visions bestowed by those brains there is very little of the comic left in the show. It seems likely that most of these changes are the brain child of Thomas and Ruggiero.

Given the rush to bring comic properties to the small screen, it’s also likely that execs have seen a multitude of pitches based on existing properties.

But were Thomas/Ruggiero looking for a comic to pitch on spec, or was iZombie suggested to them? Knowing would paint a clearer picture of how Liv came to be who she is.

For now we can only guess at the creative process behind Liv, but we can look for clues in the origin of Veronica Mars.

Before Ruggiero started working with Thomas, Veronica Mars started its life as a YA novel. Its lead was a teenage boy detective named Keith Mars.

The novel was shelved when Thomas began writing for TV. While he wrote scripts for shows like Dawson’s Creek, the teen detective idea was still cooking on the back burner, slowly changing. It became a TV show, and a stylized noir. Texas became California. Keith became Veronica.

As he considered the themes he wanted to address including loss of innocence he introduced the idea of Veronica’s sexual assault. It became integral to the character and to the show.

The network was reportedly not pleased with Veronica’s rape. They wanted it cut, and there was a heated debate between Thomas and network executive. Thomas won in the end, but it’s clearly not a fight he forgot.

Veronica’s assault was frequently cited by critics and fans as something that set the show apart from other teen dramas.

Not to create a false dichotomy, but it’s easy to wonder if Veronica’s assault saved the show from being a forgettable flop, or was the one thing holding the snappy teen noir back from becoming a mega hit.

Perhaps it’s a mistake to look for meaning here. Maybe Thomas and Ruggiero are just surfing the genre zeitgeist and trying to stay employed. Perhaps Liv’s similarities to Veronica come from a couple of artists staying close to their comfort zone.

But one things is certain: our cultural discourse is engaging survivors in a way they never have before. Who survivors are, how we treat them, and how we tell their stories has never been a more vital issue.

So a show that tells the story a survivor of sexual assault is important, even if the show won’t or can’t admit what it is.

Eli Keel is freelance arts and culture journalist based in Louisville, Kentucky. YES WE DO have arts in Kentucky. Honest. He also writes plays and poems. Tweet him @THATeli.

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Published: May 12, 2015 10:47 am