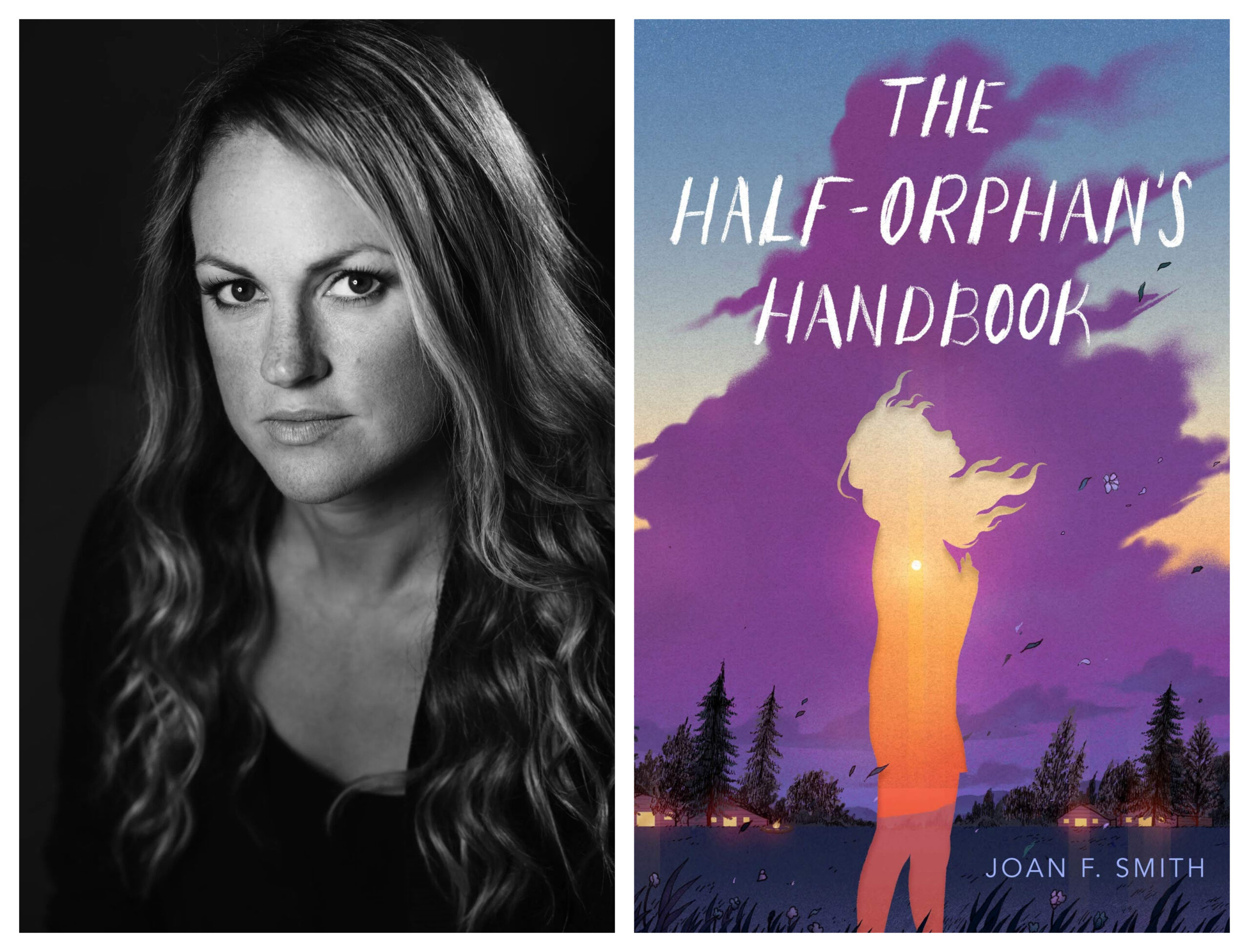

AUTHOR ESSAY: Joan F. Smith, Debut Author of The Half-Orphan’s Handbook, on “The Grieving Place”

Content warning: Discussion of suicide.

The first day of my last teenage job is the same one I learn of my father’s gambling addiction and his intention to die by suicide (by way of a failed overdose). My mother—the same woman whose not again, he left a note floats over the lofted staircase in the early hours of this March 14th, unlocking a secret I do not know will change me forever—refuses to let me stay home from my scheduled training at a local ice cream shop, glibly referred to as a “dairy bar.”

I am seventeen. I am bereft and confused, but I follow rules, so I show up to my new job in suburban Massachusetts, don a navy-blue hat and t-shirt marked Crew, and follow the trainer, a well-seasoned twenty-year-old with a Boston accent as thick as my naiveté.

She leads us through the main store area, the deep freezers, and the basement, where I would never return despite working there for the next four summers. After she steers by cardboard stacks of boxed cups and cones, towers of plastic spoons, and giant silver canisters of nitrous oxide (the more reckless employees will get fired for using these as ‘whip-its’), we pause by a Trojan condom wrapper gleaming on the cement floor.

Blue foil, torn top. In that moment, I remember a decade or so previously, insisting my parents tell me what a condom is during a neighborhood dinner party. My mother says it’s something men use to keep themselves clean. For the next few years, I think of it as a male loofah.

“I wonder whose that is,” the trainer remarks slyly, skirting it on her way back upstairs. As if any of us newbies know. All I can think of is my father, lying in a hospital bed, deeply regretting he is alive.

I finish the day with the bite of cold metal against my bare forearm, the not-altogether-unpleasant smell of dairy freezer in my nose. I experiment with the precise amount of pressure to apply to a cone: enough to anchor the scoop on top, not so much it cracks into cross-hatched shards. My right bicep learns a new muscle memory, and I discover other things while slinging cones that day, too: frozen pudding is barely-hardened soup, pistachio is basically dry ice, vanilla scoops like a dream. I will not unknow these scents or sensations for the rest of my life.

To this day, I wonder why my mother forced me to go, inexorably linking my father’s new identity with a teenage job, with, of all things, ice cream. Did she want to hide what was happening? (Yes.) Was it fear of me begging for movie money that summer? The desire for me to move on? Enter my “new normal”? (Did you just shudder at that phrase, too?)

###

Six years later, when my father ultimately takes his own life, I spend a week at my childhood home and re-learn the four walls of my stall shower. I stare at white stenciled hearts lining the ceiling, which my mother painted herself because we couldn’t afford a wallpaper border, a sentiment that never made sense to me as a child. It is at that moment that I develop the habit of showering without a vent fan on, which is a terrible habit for any homeowner to have, one my husband despises today. But it is the only way for me to scald myself with hot water and create a steaming vestibule before I jam the water back to cold, flipping back and forth between the two extremes the same way I alternate screaming into my fist with a near-blissful numbness. You are feeling something, I think. A hot-caramel sundae of despair.

In that shower, I compose my father’s eulogy. I think of the details we remember once someone we love has died, usually the ones we never ruminate on when they’re living. Now, I wonder what my children would say about me: I eat two freeze pops when I only allow them to have one; I burst into parodied song multiple times a day; my jaw juts out when I’m angry the same way my father’s does, but they don’t know that.

I do not properly grieve my father’s loss until I commit to therapy, and I have the ability to find, access, and pay for this therapy—and, luckily, I find a therapist with whom I feel safe, a luxury and privilege not afforded to millions.

When I finally recover from my anger at being left behind, I grieve all over again, because all I can think about is my father’s mindset. It turns out general writing advice and my therapist’s suggestions are siblings: Use your senses to ground yourself in space. Who you are, what you care about, the tactile sensation of your surroundings: Day to day, these are all things we should pay attention to as we experience them. Sometimes, I learn, your sense memory is what makes your feelings come rolling to your emotional surface, grinding at what you think are the healed nerve endings of your psyche. I call this the grieving place. The Little League fields of my hometown, where I ate three-dollar dinners consisting of salted pretzel rods, sugared snow-tops of fried dough, and French fry trays, where thousands of kids dusted their baseball pants with one American rite of passage or another, is the same place I pound the windows of my father’s car the night he died, when I am the one to find his abandoned vehicle. Audience applause, the crack of a bat, the last breath of a man. One place, peaks and valleys.

Five years later, I hemorrhage while giving birth. Two doctors shout between my legs. I stare at the ceiling, which is not stenciled with white hearts. A nurse leaves the TV on, and my daughter comes into the world along with a news report about Isis. Having abandoned Catholicism sometime on that hallmark March 14th of my childhood, I do something I almost never do and ceiling-talk to my father. Because I am full of a kind of love that I didn’t think was possible, I demand he barters with who or whatever’s above us if something is there and let me live.

Clearly, I do, and on a March morning a year after that, I board a plane to California to visit my brother and attend a writing conference. I am exhausted from a stint in the hospital with my feverish one-year-old less than twenty-four hours previously, but I am jacked up on both caffeine and the sensation of being alone. Like grief, I learn, parenthood is peaks and valleys. Joys and muddling anxiety. While awaiting takeoff, I read an article covering the anniversary of the closure of a 9/11 grief camp. They don’t need to hold the camp anymore, the article says, because all the kids have aged out.

I pause my reading. I am often preoccupied by the “what if” game of how my childhood might have gone if I’d been fully traumatized (Can you be partially traumatized?), if I’d lost my dad during one the times he’d attempted suicide years before, instead of when I finally did.

This camp—America’s Camp—helped hundreds of kids for a decade. Tucked safely in the Berkshires, the kids who lost a parent in 9/11 met every year, summer after summer, at a sprawling natural setting that gave them access to therapy, a s’mores-and-activities-filled-schedule, and most importantly, each other. The people who shared the same grief, the people who will not define you by the loss of a parent, because everyone there has.

All of my friends still have at least two parents. No one close to me has lost a friend or relative to suicide. Grief camp, I think, closing my eyes and laughably trying to sleep. My mouth fills with the taste of a salted chocolate biscotti, the first thing I eat after my father dies. I imagine what it might be like, to abbreviate responsibility and spend two months investing in my emotional well-being. I marvel that instead of the admonishment to not tell anyone about what’s happened—to carry stigma until it is part of the marrow of your bones—children are encouraged to share their stories with one another, to meet friends in the same shitty club they’re in, to find a way to remember the pain of old wounds instead of ripping them open again. I am filled with a sudden sadness at the closure of this camp, followed by a strong desire to somehow make use of that aged-out space. (I do.) Years later, when the pandemic starts killing more people every week than September 11th did, I will remember the shaft of light that enters the airplane as we land in California.

###

2020 gifts all of us a new-old grieving place, confined to the walls of our homes. Society violates its own social contract. Decisions are weighty and innumerable. My husband and I volley questions at one another the way we used to trade funny tweets. How long can we leave mail? What is your grocery-wiping process? What about the people who can’t eat? Should I wear a mask to run? Is he going to make it out of the ICU? Did you hear from her? Did you?

As a nation—really, as a world—we will forever grieve an entire year of our lives. We are glued to the news the same way we might have been in September of 2001. Re-traumatized, we seek answers to unknowable questions and place orders for disposable masks. The vaccine is the shining beacon of hope. I flinch at the term “pre-existing condition,” recalling my father’s asthma in the recesses of my brain while I read the If You Give a Mouse a Cookie series to my kids. Because not unlike Mouse, if you give my father a Nebulizer for his asthma (as he reveals in his final suicide note), he’ll use it to vape weed like the kids of the 2010s would, like the whip-it boys of the dairy bar 2000s do.

If an estimated 1 in 7 kids experience the loss of a close family member before this—how can we grieve, move on, if we turn the same doorknobs, wash our hands at the same sinks our loved ones did, if we can’t go to grief camp?

I know what my therapist would say if I tell him that I now associate the scent of the inside of disposable masks as a new way to ground myself; worse, I know what he’d say if I tell him I greet my well-worn anxiety like it’s a crappy high-school boyfriend. It turns out it’s imperative we create these spaces, these senses for ourselves—our own mini-grief camps. We must forge connections with those around us or online, we must engage in sourdough starter dialogue and vote and avoid clickbait, we must find a place and a space to grieve, to remember, so we can find ways to climb one of those peaks again. He might even tell me to eat ice cream.

In summer, I treasure the slick of coconut lip sunscreen and wear hats to ineffectively prevent my face from freckling the way my father’s did. I take my children out for ice cream, wondering if I’ll catch a hint of that dairy bar freezer air. But the next time, I find that scent is not in a sun-baked parking lot as a customer. It’s not at the grocery store, nor is it in the oddly tall freezer at the new house my father will not see. I am caught off guard when I find it at the ice-skating rink, tinged with smoothed, manufactured ice, where I take my daughter to learn to skate. I glance at her, grateful she cannot know that this sense memory walks me back through time to a day shaded with a strained bicep, to a blue foil wrapper on a gray cement floor, to a man on a stretcher. I wonder what this place will mean for her someday, and which spaces she’ll grieve, which she won’t. I squeeze her hand three times, inhale, and watch her go.

(featured image: Imprint)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]