Her perfectly shaped forehead glistened as sweat trickled down her temples. I studied how her hair undulated when we biked around the block. We were powering through each pedal, and without exhausting ourselves, we lifted our legs once we gained enough momentum for our bikes to move by themselves. There were also days when I asked for her to come over and play some Street Fighter or Disney’s Hercules on the PlayStation, but the answer was consistently “no” because her parents have probably installed a microchip sensor right underneath her nape to monitor her responses. Calling her obedient is an understatement. Regardless, I thought she was cool and neat and pretty and all the other words a 9-year-old girl could fathom as compliments to give for a girl she liked.

Every now and then, I would lucubrate on what could have happened if I had told her that I liked her. Though she was the first girl I strongly liked, she was not the only one. Repressing to acknowledge my interest and confessing it to someone who is the same gender as I am has been a consistent defense mechanism I’ve used growing up.

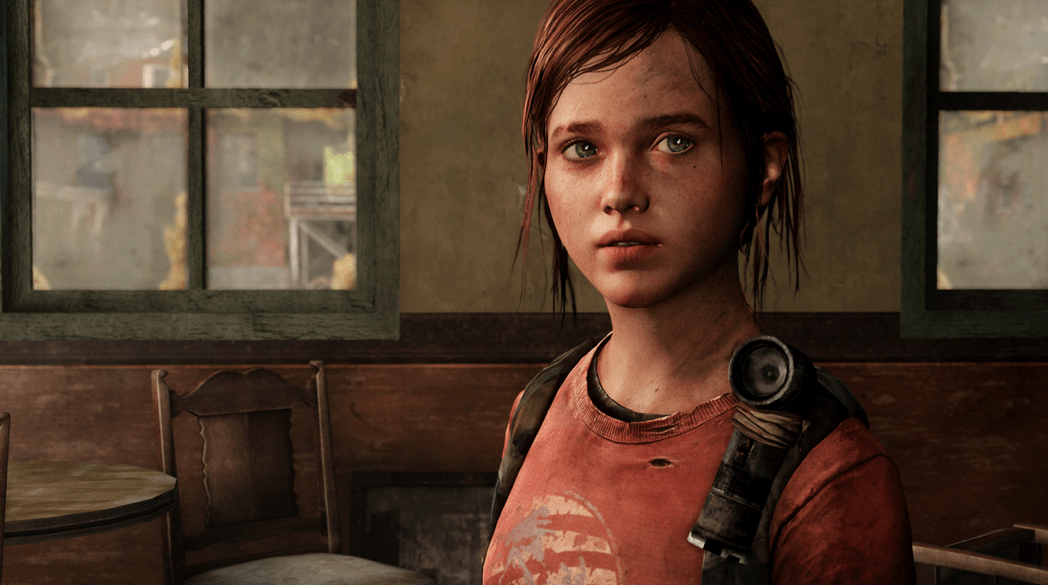

But as I was playing The Last of Us, I noticed some repetitive nuisances I did that eventually led to a series of questions about said interest. There were multiple moments when I caught myself saying “Ellie and I would have been best friends” over and over. But what I really meant to say was much more than that and it quintessentially comes down to “Ellie and I would have been lovers.” The detrimental facet that resonated after I have stowed away my feelings for women were not the possible romantic relationships I could have established but how apologetic I became about who I am. Phrases like I’m sorry would become habitual tics to refrain myself from accepting this understanding.

The Last of Us quickly became a serendipitous reminder—a shower of nostalgia—about what attracted me to the first girl I liked. Her personality was highly similar to Ellie and it did not click at first, but as the game progressed, I started referencing mental images of Ellie in my head that represented characteristics I liked about my childhood crush.

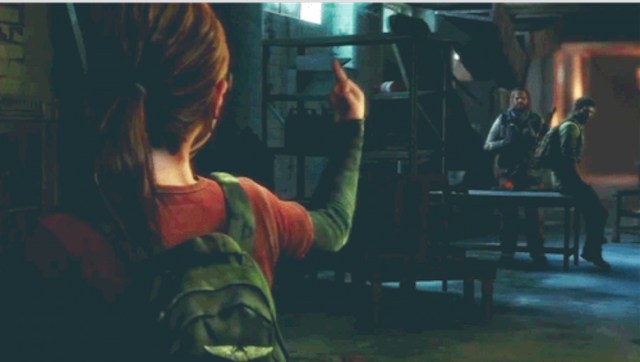

Cutscenes that poignantly reveal Ellie’s character comes in like an echo from an old Polaroid photo. An example would be the infamous scene when Ellie rifles through Bill’s miscellaneous pile of things despite being told not to touch anything. After the irritated Bill hollers at Ellie, she then proceeds by flipping Bill off. I literally had to pause the game because I could not stop laughing, and with all conviction I said, “Ellie and I would have been best friends.” Shortly afterwards, my thoughts jumped to fragmented images of myself with the girl I liked giving the finger to rubbernecking perverts.

My experience playing The Last of Us is less about surviving through a fungal infection in post-apocalyptic America with Ellie, but more about unraveling an identity I have detached as Ellie guided me back through it. To put it simply, Ellie created an opening for me to explore the basis of what attracted me to girls.

Helen Fisher’s The Law of Chemistry discusses the levels of attraction and variables that causes people to gravitate towards certain individuals versus everyone in the room. Her general assumption hypothesizes that “… people generally fall in love with those of the same socioeconomic and ethnic background, of roughly the same age, with the same degree of intelligence and level ofeducation, and with a similar sense of humor and grade of attractiveness.”

Drawing from the basic level of attraction Fisher examines, the study delineates that attraction is not immediately tied to sexual orientation, rather shared interests between individuals. As a kid, I had an inclination that I was attracted to girls as well as boys, but what ultimately determined who I liked the most is based on how well I related to the person.

This understanding was augmented even more when I played through the DLC Left Behind. Those couple of hours I spent playing as Ellie and hanging out with Riley was like waking up from an extensive coma. As cheesy as this sounds, the ending kiss scene between Ellie and Riley is comparable to Prince Philip kissing Aurora in Sleeping Beauty. The initial kiss is a realization, an instance of waking up and anticipating what the seconds, minutes, or even months ahead would be like with that significant other.

After that cutscene ended, I had to once again put the controller down because I was gushing with emotions transformed by the game. I was filled up with constant recollections of all the propitious times that were lost, where I could have appropriately expressed my affection towards a girl I liked.

Truly, The Last of Us made me experience a full narrative exploring the character dynamics of Ellie, as well as the duality of her relationship with Riley. But more importantly, this game provided me the reassurance I needed to validate me being bisexual. If it were not for characters like Ellie and Riley, I would not have had developed a backbone to accept my bisexuality. Diversity like this is significant because they give weight to representation in games.

Creative director Neil Druckman even explicitly admitted to gaygamer.net on Ellie being gay to erase any speculations from players who denied it: “Now when I was writing it I was writing it I was writing it with the idea that Ellie is gay, and when the actresses were working they were definitely working with the idea that they’re both attracted to each other. That was the subtext and intention that they were playing with from the opening cinematic when they’re holding each other’s hands for too long, or when Riley bites her on the neck; there’s that chemistry there from the get go that was important for us so that we earned that moment when they kissed each other.”

Video games are becoming ubiquitous, and like other media, they are also just as seamlessly capable of influencing users through their own narratives. When players plug into the virtual word within a given setting, they could either feel keenly connected or somewhat disconnected to the main character due to the tight narratives.

Hence, most playable protagonists are generic and likable because they call to a certain audience molded by the industry. But when characters like Ellie comes out, this promptly breaks the mold of the overhauled triple A leading roles. Another example of an astounding game that cultivates diversity is Gone Home.

Variety in games is terribly critical because it gives everyone the prospect to feel important—to have their voices heard. Acknowledgement is part of being human, and if we see ourselves in mediums we frequently consume, then won’t we feel at the least bit a sense of belongingness?

As a part of this digital society, we curate our own culture, including the types of video games we impart for the rest of the world to play. Video games have been evolving as an interactive medium allowing people to directly express and understand who they are, and I do not mean attaching a whole identity to a trademark. Rather, operating video games as a conduit to channel one’s idiosyncrasies, the parts that make us feel alive.

Upon witnessing Ellie as a character in The Last of Us and the new awareness I have gathered after playing the game, I am convinced that we play the games we want to play because we see ourselves in them.

Kaira is perpetually hungry and when she is not thinking about food, she is either busy developing games or scrutinizing ecological patterns. You can tweet to her about hedgehogs and cupcakes @zovfreullia.

Are you following The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Published: Feb 2, 2015 08:00 pm