When I was a kid, I watched a lot of Star Trek.

It’s probably worth mentioning this was in the late 1960s/early 1970s. (Spoiler: I am old.) The Star Trek I watched was innovative, groundbreaking, radical — for its time. There’s a lot to be critical of when one watches it now, but in the mid-60s it was delightfully forward-looking. Different ethnicities! Women on board! And…wow, did we really survive all of this Cold War armageddon stuff?

It was upbeat, and wildly optimistic. It was also my first exposure to science fiction almost getting it right. Because when it came down to it, there wasn’t a lot of there, girl-wise. The women were all pretty. Smart, of course, but mostly pretty. And only on occasion did they actually do stuff.

As a child, I found this sort of amorphously frustrating. They had put women in space, but they hadn’t really done anything different with them. They weren’t even reflecting the women I saw around me every day — not my mother, not my friends’ moms, not my teachers. Not me, and what I dreamed of for my adult life. Women were there in Star Trek, like decorative furniture. It was radical, and it was not enough.

In my mid-teens, I started primarily buying science fiction books written by women. I somehow acquired the idea that if it was an author I didn’t know, I had better odds of finding something I liked if the author was female. For a while, I figured it was survivor bias: any unknown woman who could get published in the genre was likely to be better than an equally random man on the shelf next to her. There may be some truth to that.

But when I look back on it now, the phrase that fits is one I first heard applied to the reading experience a few years back: punched in the face. A book written by a woman was less likely to interrupt an otherwise gorgeous narrative with a female character who seemed designed, in all of her two glorious dimensions, to slap me with the idea that the Big Science Fiction Future was not going to include me.

These days, there’s a lot of talk about how few women go into science and technology – or stay with it once they get there. I was a software engineer for twenty-seven years; I could go on for a while about that. But the short form is this: Girls are interested in this stuff. Girls are capable of this stuff. Girls fall in love with software and physics and paleontology, and they are unabashedly excited about it until someone tells them they can’t. And the longer we can put off the moment when they first encounter “You can’t because you’re a girl,” the more likely they are to say Of course I can and be able to stand up to the institutional resistance they’re going to have to slog through no matter what.

And one way we do this is to show them futures where they exist. Not just as decorative furniture, but as people. Complete people, with jobs and friends and ambitions and lives and more than two glorious dimensions.

It helped me, finding books. Books that not only included women, but women with hearts and souls and personalities and pasts and futures. They did not have to be just like me, with my strengths and weaknesses, my choices, my ambitions. I loved sinking myself into unfamiliar lives. But just the existence of complete women in these narratives meant something to me. It gave me hope that I wasn’t going to be stuck in someone else’s tiny little box.

And yet…

One of the reasons I write science fiction is because these tiny little boxes still exist. Not just for me, not just for women. It’s all well and good to have the President of the United States say “we need more diversity in STEM,” but it’s the rubber meeting the road that becomes problematic. People get attached to their tiny little boxes – not just the ones they want you to stay in, but the ones they live in themselves. Seeing you move out of yours can feel threatening. This isn’t a phenomenon limited to the tech industry.

And it gets really, really tiring, some days, to keep saying Of course I can. Even when you know it’s true.

In fiction, I can run away from home and write the world the way I think it should be. I can write women who are not only competent, but are accepted as competent, because why wouldn’t they be? They are not perfect (pro tip: perfect characters are really boring), but their flaws and mistakes and ham-fisted moves don’t happen because That’s What Girls Do. They happen because they are complete characters who sometimes make ham-fisted moves.

There’s no way to shake society out of the writer. It’s where I live. A lot of it I try to build and improve. A lot of it makes me angry and tired. And because I live in the here and now, my posited future is rooted in the here and now in ways that I can’t see. It’s possible that when my book is as old as the original Star Trek (please forgive my mad authorly fantasy of still being in print by then) people will say “Wow, what a limited vision of women. It’s a start, but it’s not enough.”

And it’s true: what I write is not enough. But with luck, it’s one small step in the right direction.

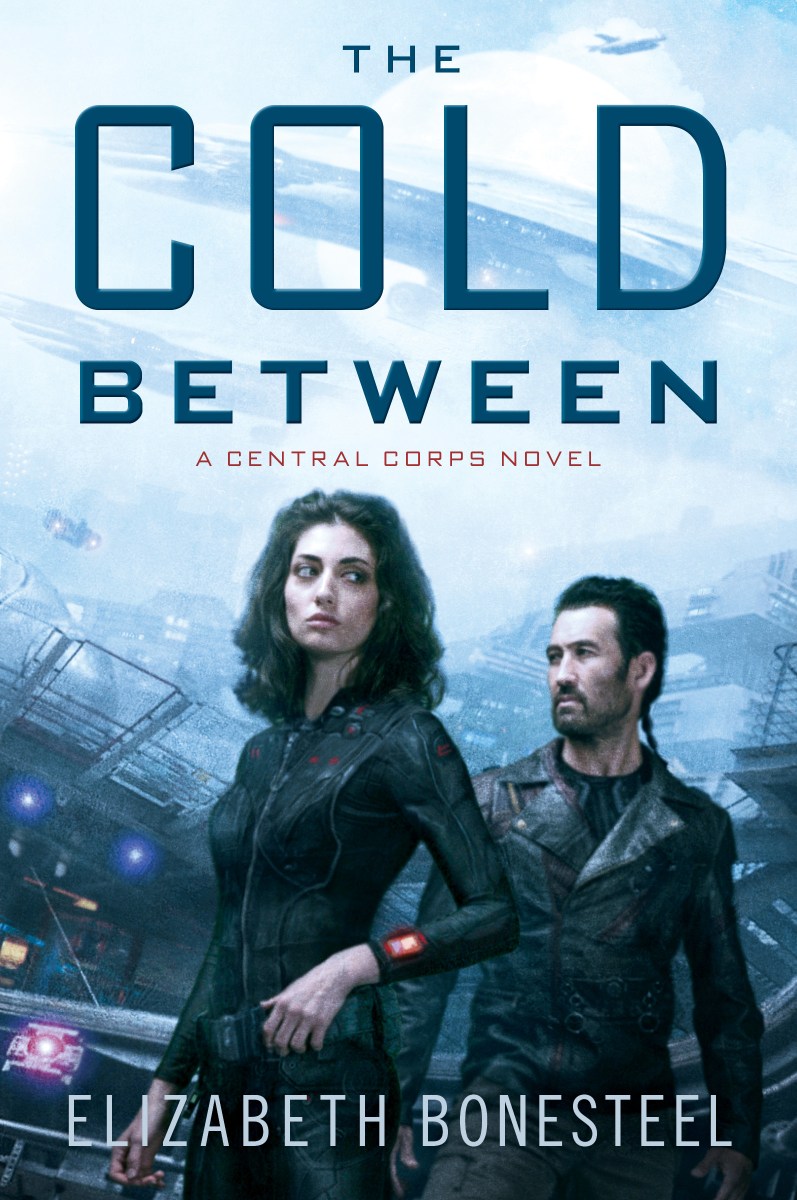

Elizabeth’s book The Cold Between is on sale now.

Elizabeth Bonesteel began making up stories at the age of five, in an attempt to battle insomnia. Thanks to a family connection to the space program, she has been reading science fiction since she was a child. She currently works as a software engineer, and lives in central Massachusetts with her husband, her daughter, and various cats. Massachusetts has been her home her whole life, and while she’s sure there are other lovely places to live, she’s quite happy there.

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Published: Mar 10, 2016 02:19 pm