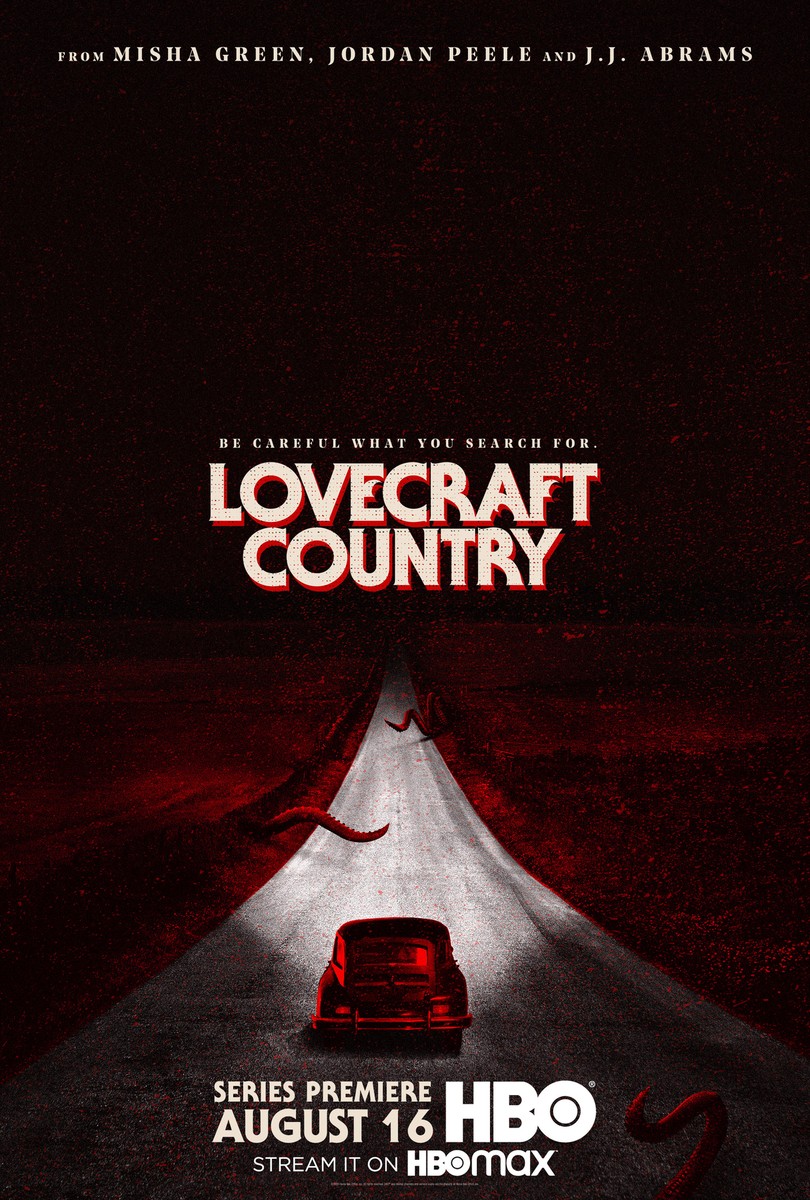

Lovecraft Country Allegorizes H.P. Lovecraft’s Monstrous Racism Through the Reclamation of the “Other”

About a month ago, Lovecraft Country premiered on HBO to instant acclaim, and for good reason. Misha Green and Jordan Peele’s latest horror venture takes an unflinching and immersive look at how the monstrosity of racism manifests amidst a supernatural landscape.

Set during the 1950s Jim Crow era, the series follows Atticus Black, his Uncle George, and his childhood friend Letitia as the three embark on a road trip across a deeply racist and segregated America in search of Atticus’s father. Along the way, they discover that the monsters hunting them are not confined to the horrors dreamed up in H.P. Lovecraft’s books.

And truly, the themes explored in each episode give an illuminating portrayal of the monstrosities that are birthed from bigotry, intolerance, and just plain racism, and with the climate of 2020 America bordering dangerously close to a re-emergence of Jim Crow levels of racism, these issues and conversations are more timely now than ever.

But what makes Lovecraft Country so powerful is not simply its examination of racism through a supernatural lens—rather, the power in its subversion of cosmic horror lies in its challenge of H.P. Lovecraft himself.

For those unaware, H.P. Lovecraft was an extremely racist and bigoted man—even for his time. (Lovecraft lived from 1890 to 1937.) His views espoused white supremacy, Nazi sympathizing, and a level of derision towards Black and Brown people that won’t even be dignified with further description.

The ongoing challenge in science-fiction and horror circles alike has been grappling with the inexcusable bigotry of Lovecraft against the obvious brilliance of his stories. How can one separate the artist from the art, when the art itself is built upon poisonous, destructive ideals?

You can’t.

(image: HBO)

The very core of Lovecraft’s mythos is steeped in racism. The very notion of the cosmic horror created in his stories is based upon the fear of the “other” and the primordial horror that manifests when the universe challenges your perception (and expectation) of reality.

And Lovecraft’s expectations of reality invoked white supremacy in its most destructive form: racial purity, segregation, and the dehumanization of minorities in the most deplorable fashion possible.

Minorities—Black, Brown, and Indigenous people—were the real monsters of Lovecraft’s imagination. This is obvious in his stories, whether it’s through the thinly veiled allusions in “The Horror of Red Hook,” or the blatant metaphors of “The Shadow of Innsmouth.” In Lovecraft’s view, minorities were sub-human at best, and monstrous at worst—always, though, in such close proximity to the beasts of the Elder Gods pantheon (Cthulhu, Yig, Alala, Gleeth, etc.) that one cannot tell where the human ends and the monster begins.

That’s where Lovecraft Country comes in. Rather than adding on to the established, archaic mythos of Lovecraft’s universe, Lovecraft Country masterfully reconsiders the caste of good and evil to bring forth an interpretation that challenges the notion of what a horror is supposed to look like. That powerfully reclaims the “other” by filtering the world through the gaze of Lovecraft’s original “monster.”

Making Atticus—a Black man—the protagonist of Lovecraft Country was an intentional decision. In so many stories (Lovecraftian or otherwise), Black people are often viewed through a lens of suspicion, or a detachment that makes it difficult to conceptualize them as grounded, three-dimensional characters. In Lovecraft’s mythos, Black people were reduced to nothing more than “beasts in semi-human figures … filled with vice” (On the Creation of N****, 1912).

But who has the right to say what makes a beast and what makes a man? And furthermore, what does the world look like through the eyes of those who’ve been unfairly and incorrectly branded as “beasts”?

In many ways, it looks much more frightening than anything cosmic horror could hope to conjure.

Because through Atticus Black’s eyes, we are introduced to a horror that’s unsettling because of how familiar it is. Because of how deeply ingrained it is in the collective anxieties of Black and Brown people. Because of how grounded it is in an unfortunate reality. What’s there to worry about vast, opaque cosmic terror when the true danger may be lurking in the eyes of the very real human in front of you?

Adding on to that, how does one navigate a world of beasts and men while embodying the hyper-awareness that their being, their body, their very personhood is something automatically deemed a threat?

Lovecraft Country doesn’t answer all the questions, but it sure does a good job of trying.

(image: HBO)

By humanizing the “other” and fully realizing them as nuanced, introspective, and multi-faceted individuals, Lovecraft Country cleverly unravels the core theme of Lovecraftian horror to propose what weight a cosmic horror can truly carry when it’s expanded to include other diverse perspectives—and, with that, other paradigms entirely.

Because sometimes, it’s not the horrors of the vast unknown we should be worried about.

Perhaps, it should be our neighbor next door.

(featured image: HBO)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]