Though New York Comic Con has come and gone, we here at Geekosystem were lucky enough to meet up with some amazing people at the massive celebration of all things geeky. Here’s an account of some of the mysterious creatures that leapt out and attacked us along our epic quest.

The only thing between Luke Crane and myself is a box set of his latest roleplaying game creation. He didn’t know I was coming, and I didn’t know I was going to see him, but it quickly becomes obvious that it didn’t matter all that much to him. Crane, who is the creator of the Burning Wheel roleplaying system, is a fast thinker and a fast talker. There’s nothing wasted about this man — he’s slim, with close cropped hair and a sharp mind. Which only makes sense, since Crane has spawned games that have cut to the very heart of roleplaying, and reworked it from the inside out in his games.

For the uninitiated, Burning Wheel is a pencil and paper role playing game in the vein of Dungeons and Dragons. There are dice, there are sheets of paper, and the players say their intentions instead of moving pieces around a board. But Burning Wheel, while drawing from the traditions established by D&D, is very much its own game. To take a superficial difference, the iconic 20-sided dice of D&D will find no home on a Burning Wheel table. The game shirks such exotic things, and uses simple, ubiquitous six-sided dice instead.

But as a game, there are deeper, subtler differences. When I asked Crane to describe the game, he said exactly what is written in the beginning of the game’s first manual: Burning Wheel is about fighting for what you believe in. “And by ‘fighting’ I mean stabbing each other in the face with sharp metal objects.” He continued, “Burning Wheel is a game for people who have gotten bored with other roleplaying games or want something different; a deeper, richer experience beyond what traditional roleplay offers.”

In this case, “traditional” means D&D and its ilk. Though thats not to say that Crane has not played the seminal dice-throwing RPG — quite the opposite. It’s clear from reading his books that roleplaying games are near and dear to his heart. It’s just that like many creators — notably, those of an indie persuasion — he wanted to make the kind of game that he wanted to play.

His games are about stories and characters, and he shirks things like loot and exotic weapons. For him, a good game isn’t about bean counting and grinding. “It’s not about power leveling, it’s not about experience points, or magic items or anything like that. It’s about taking a character through a dramatic change in belief.” In fact, when you create a character in Burning Wheel, he or she receives abilities from the history, or “life path,” of the character. As a player, you also decide what, exactly, your character believes in.

These beliefs, which are written on the character sheets for all to see, are the crux of gameplay in Burning Wheel. In his manuals, Crane encourages the people who are the architects of player’s games — called Dungeon Masters, or DMs — to focus on challenging the beliefs of player’s characters rather than simply guiding them on a long and winding road filled with interchangeable baddies to hack and slash. In fact, overbearing DMs that drag players along rather than being dynamic storytellers are carefully checked in Crane’s game.

But more than targeting a particular kind of DM or “big RPG,” to coin a cliche, Crane says his sharp words in those books are there to define his game. “I really have an axe to grind with me in those books, more than anything else,” he said. “There’s more than one way to play roleplaying games. I’m a little bit toothy in Burning Wheel Revised,” the second edition of the game’s rules, “but I just want to stake my ground. We have a different perspective on what we expect you to do in this roleplaying game.”

It’s fair to ask what kind of game he means since, after all, there are numerous pencil and paper RPGs. But while some use vampires as lead characters, and others have a high-fantasy setting, and still others take place in a future where everyone wears Motocross helmets at all times, Crane really is pushing a fundamentally different game. The first time I went through a Burning Wheel game, I was stunned that there was no defined system for keeping track of money. Instead of carefully accounting of my character’s accumulated wealth, I roll dice to see if I have the money on hand at a particular time.

It’s little things like this that add up to a different kind of game, one that really is less about players and game mechanics and more about characters and stories. For instance, Burning Wheel has an in-game method for dealing with the arguments that often take place out of game, in so-called “meta-gaming.” To streamline these often tedious arguments, Crane created a system called Duel of Wits. When it came to discussing this particular aspect of the game, Crane reflected on some of his fellow players that he’s known over the years that helped form his views on gaming. “I have some great roleplayers as friends,” he said. “And they can talk your pants off. And I hate them.”

“Because after roleplaying with them for like 10 years, it’s like ‘Oh, here goes Brian again and he’s gonna keep going until we’re all charmed.’ Or, ‘Here goes Rich and he’s gonna kick people in the face until he gets what he wants.’ So I wanted to make social interactions fair. I wanted to have it based on character skill and not on player skill.” To some, this might seem like a step too far, since it would seem to hamstring actual play. After all, what is a game if not practice, and how else do players get better if not through developing their own skill?

However, Crane insists that Duel of Wits is about moving the game forward, and above all: Actually solving disputes. “We wanted to make sure that the focus of social interactions was compromise. Not just, I roll, you do what I want. But we roleplay, we argue, and then we come to a compromise.” Grinning impishly, as he often does, Crane added, “And we totally did it.”

Though not as well known as D&D or other RPGs, Burning Wheel has done quite well in its own right. In the nine years since its inception, there have been two printed editions of the rules with several supplemental manuals and a third all-new version of the rules with entirely streamlined, re-written explanations for the entire game. Burning Wheel Gold, as it’s called, went on sale this summer and completely sold out in pre-orders.

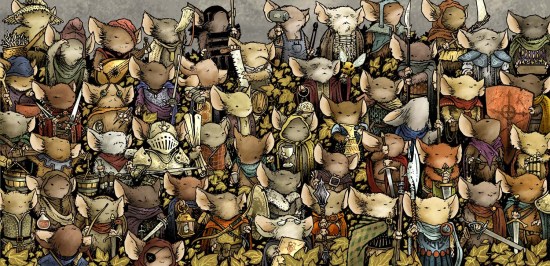

However, it was an unlikely alliance between Crane and a Michigan comic book artist that opened up an entirely new branch of Burning Wheel. The cartoonist is David Petersen, who was sitting signing copies of his critically acclaimed Mouse Guard comic books just a few yards behind Crane. A few years back, the two of them produced a roleplaying game based on the settings and characters of Petersen’s Mouse Guard universe — which is populated by various anthropomorphic creatures, and guarded over by noblemice of the (mouse)Guard.

While Petersen’s comic is a lot of fun, I was curious why Crane would want to put his efforts into someone else’s game. After all, he’s already got big ideas and has had success bringing them to market himself, and on his own terms. With a smirk, Crane quipped back, “Wouldn’t you?”

“If David [Petersen] came to you and said, ‘Hey, your Burning Wheel game sounds kinda neat. Do you wanna design a Mouse Guard version?’ What’s the answer? The answer is, ‘yes.'” Crane recalled that when Petersen approached him, it was still early in the life of Mouse Guard — before Petersen’s wildlife fantasy started to turn heads. “But I saw it comin’,” said Crane. “So it was naked ambition.”

With Crane, a fortuitous alliance doesn’t mean a shoddy product. Instead of shoehorning a new setting for Burning Wheel, Crane went back to the drawing board and brought forth a derivative, but unique, game. Think of it as one of Darwin’s sparrows; the games are closely related, but evolved to fill a specific niche.

“I wanted to create as stripped down a version of Burning Wheel as possible while still retaining its quintessential elements,” said Crane. So while the Mouse Guard game has a fixed setting and character types, it still has the burning spirit of Crane’s progenator RPG.

Moreover, he tweaked the game so that it would, perhaps, appeal to RPG newcomers and the diverse audiences attracted to Petersen’s books. Crane says, “I wanted to write a game text which did not use imperative or negative. It was only positive statements.” This means that in Mouse Guard, you’ll never be told “you must,” only “you do.”

The simplicity and robustness of Mouse Guard as a game underlines a major strength of Burning Wheel: It seems nearly endlessly adaptable. Want to use werewolves in your campaign? Burn your own werewolf characters, or go online and see what other players have created. Interested in throwing off the whole fantasy setting and doing a Scott Pilgrim game? Take the Magic manual and turn spells into songs, create Canadian lifepaths for your characters, give them musicial beliefs and let the story begin.

Though it’s certainly true that Crane owes an enormous debt to the games and players that have come before, what he and his games represent is something far, far larger. For decades, if you were going to play a pencil and paper RPG, you were going to use D&D or something very much like it. There have been others, and they may have been fine in their own right, but Crane’s work is a true rethinking of what it means to roleplay, and is written from a perspective very different than older games. Unlike his predecessors, Crane has the advantage of gaming for years; he has not only played the games, but he has seen how real-life players play the games.

That’s Burning Wheel: It’s a game for players with a story to tell, and adventure in their hearts.

(image credit Justin Ouellette)

Published: Nov 2, 2011 12:39 pm