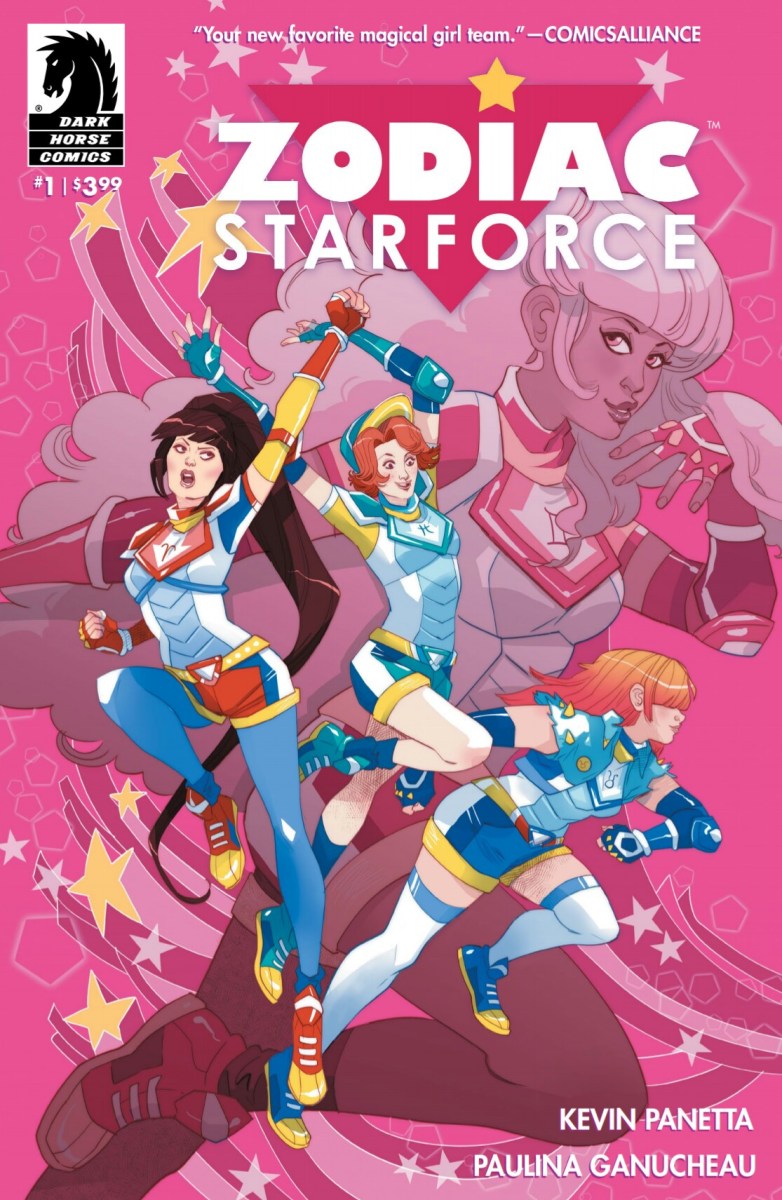

Magical girl media has more to offer than we think. Especially as more of our beloved heroines are becoming symbols of fighting more than just gender roles – as Zodiac Starforce continues to show us, the magical girl genre is one that celebrates that heroines can be powerful, capable, and queer.

The magical girl genre dates back to 1953, with Princess Knight considered the prototype magical girl anime by some scholars. Himitsu no Akko-chan (1962) and Sally the Witch (1966) also followed suit, but it wasn’t until the debut of Sailor Moon that the magical girl genre really took off for both Japanese and international audiences.

Queerness within the magical girl genre is not anything new, but rather, it’s evolution has been something that has been an interesting trend to follow as the genre itself expands. The celebration of femininity and femme influences are seen everywhere in magical girl media – the pink and/or heart-shaped weapons, the cute outfits, the magical sequences – but also work as a fascinating backdrop to exploring gender and sexuality in a way that goes beyond the restrictions of the male gaze. Modern audiences see this done with Sailor Moon, as Naoko Takeuchi not only introduces the first canon lesbian couple in a magical girl series (Sailor Uranus and Neptune, if you weren’t aware), but she also introduces gender as fluid and sexuality as individualized, as we can see with the Sailor Starlights.

But because of these trends, there’s been a lack of similar media produced for Western audiences. This is one of the many reasons why Zodiac Starforce is such an important comic series. After reading and reviewing the first issue, I knew I would be hooked. At its core, Zodiac Starforce goes beyond simply being a new staple within the magical girl genre; it continues the tradition while also turning it on its head, allowing for both new and old rules to be explored.

In Zodiac Starforce #2, a subplot focused on the developing relationship between Lily and Savi brought out many important emotions for me. Not only was it refreshing and liberating to see a queer couple’s relationship normalized in such a major way, but seeing

Lily – a femme Black girl with a massive ‘fro and a penchant for pink – seen as an object of desire without the dangerous sexualized undertones that come with desiring Black women in other media, was incredibly important. It was more than just a breath of fresh air to see Lily and Savi’s relationship develop in this issue. Though the magical girl genre allows for the safe exploration of sexuality among its heroines, convention can still find its way in. Lily and Savi’s relationship is monumental because it represents a symbolic middle finger to the troupes and stereotypes that hold back individuals who shoulder the burden of being marginalized in multiple ways and struggle for recognition. The last visible example of magical girl media doing something similar was Anthy and Utena in Revolutionary Girl Utena. Allowing for a dark-skinned woman of color to be seen as desirable without sexualizing her is revolutionary and almost unheard of in most media. But this gives way for hope – Lily and Savi’s relationship struck a chord in me that the magical girl genre can accomplish much more than it’s often given credit for.

The ever-growing list of fan art, letters, and posts on social media blogs proves that I’m not the only one that feels this way. But queerness, like other facets of our identities, deserve to be displayed beautifully and in varying ways on the page and on screen. The magical girl genre allows for this because it celebrates the subversive.

Cameron is a writer, activist, and professional fangirl from New Jersey. She is committed to shifting ideas of diversity in nerd culture and SFF, one Internet rant at a time. Her work can be found on her blog, as well as various other places online. You can also find her on Twitter.

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Published: Nov 4, 2015 6:29 PM UTC