The Uniform as Costume: From McDonald’s to Drag Balls

A news story about a Taiwanese McDonald’s branch wearing Taiwanese military uniforms as part of a New Years campaign (other branches have Minion themes, zombie themes, etc.) made national news a few weeks ago. Reports also added that it’s illegal for non-military civilians to wear the uniform without permission, and it’s possible that they might be subject to a fine.

Many expressed that wearing a military uniform recreationally demonstrates a lack of consideration toward the history, meaning, and significance of these outfits, as well as disregard for the individuals in the military. I asked my dad, who was in Taiwan’s Air Force, what he thought about the whole story and he told me he found the campaign “disrespectful” and he hoped that the incident would function as a caution towards similar ones.

However, what happens when a non-military civilian decides to wear a uniform (or something meant to resemble a uniform) with full understanding of what it represents? A couple of examples come to mind, like Margaret Cho’s “North Korean general” bit at the 2015 Golden Globes.

Cho’s acting as “Cho Young-ja” dealt with some backlash, and I think there’s a lot of valid critic about how making jokes and memes about North Korea makes it easier for the public to dismiss the fact that it’s a totalitarian dictatorship. However, Cho, who comes from mixed South and North Korean descent, understands exactly what her uniform symbolizes. While the jokes didn’t really land for me, I recognized that Cho donning the uniform was a form of protest. As she stated, “I’m the only person that can make jokes about it and not be placed in a labor camp, so I think I’m pretty lucky,” and “you imprison, starve and brainwash my people, you get made fun of by me.”

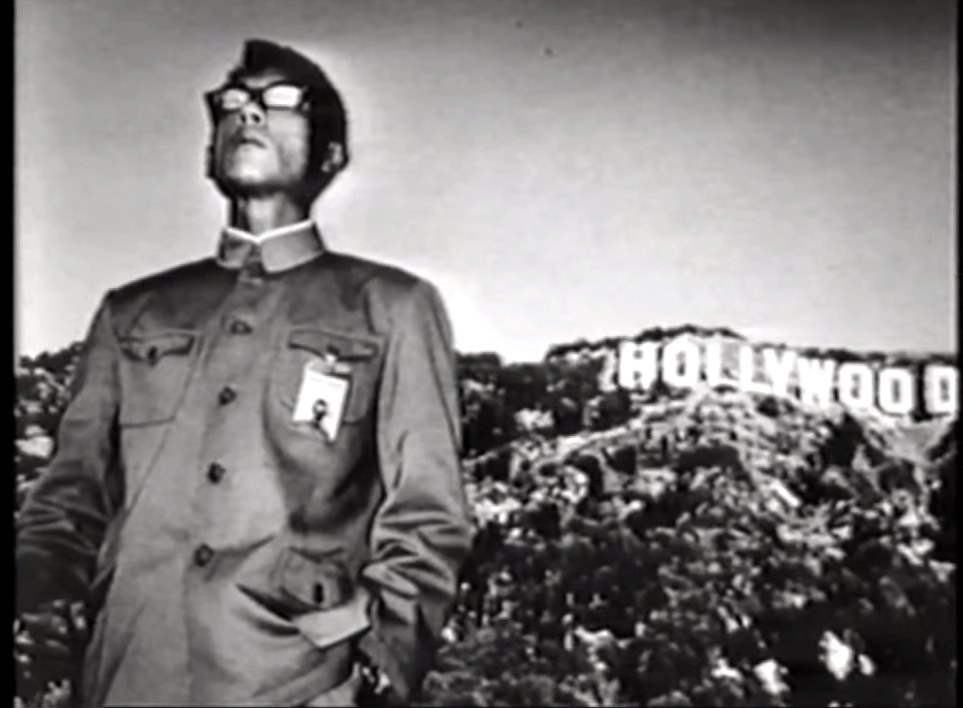

While the examples I’ll be citing here might not be what we immediately think of when we hear “cosplay,” and I doubt any of these individuals identify as “cosplayers,” I think they’re valuable examples of ways that costumes in performance art can have powerful messages. Long before Margaret Cho donned her North Korean general outfit, artist Tseng Kwong Chi had his “Mao suit.”

Tseng, an artist from the ’80s, had a series where he adopted a Chinese communist persona and photographed himself in various tourist attractions. In putting on the suit, Tseng explores Western stereotypes, notions of nationalism, and more (Tseng’s family fled China to escape the communist regime, and he spent parts of his life in Hong Kong, Canada, Paris, and New York). He also saw a change in the way people treated him once he put on the suit, giving him new forms of access.

From the perspective of someone from the United States, these instances of performance art or protest art don’t seem that controversial. However, I think the topic for many becomes more sensitive when we ask what the implications are of donning a United States military uniform. Federal law, specifically 10 USC, Subtitle A, Part II, Chapter 45, Section 771 states:

Except as otherwise provided by law, no person except a member of the Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps, as the case may be, may wear –

(1) the uniform, or a distinctive part of the uniform, of the Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps; or

(2) a uniform any part of which is similar to a distinctive part of the uniform of the Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps

Section 722 gives certain exceptions for individuals who are not active, those with special authorization, theatrical productions, etc. In the documentary Paris Is Burning, which looks at the culture of drag balls in the ’80s, there are many images of participants walking in military uniforms or military-esque outfits for the category “Military Realness.” The film talks about the concept of “realness,” or to “look as much like possible as your straight counterpart.”

At a time when homosexual and transgender individuals were banned from the military (with the ban on transgender personnel only ending last year), I read donning the uniform as resistance against that exclusion and other forms of structural discrimination or violence. One participant says that by passing, they prove they can be someone (a businessman, a general etc.), by performing and looking “like” one.

I spoke to a close friend who did the Army Reserve (UK) to ask him what he thought about people wearing uniforms as costumes. To the McDonald’s example, he told me that he’s seen people wear uniforms like his for fun or as jokes, and highly disapproves. He explained there’s a long tradition to these uniforms, and an excruciating amount of maintenance that goes into them. When I brought up the other examples, he hesitated in calling it “ok,” but acknowledged it was “different for art” and “understandable.”

In the United States, it’s permissible to wear uniforms in theatrical productions so long as it “does not tend to discredit that armed force.” Like any sensitive representation, I think the question to ask is “who benefits from this?” Understanding what the United States uniform symbolizes, both the positive side that we’re taught and the negative that’s more uncomfortable, may make these uniform-as-costumes more “understandable” (or possibly worse for some, as it reveals a larger critique rather than simple ignorance). Needless to say, understanding the implications and wearing them to brag about fake accomplishments, just for fun, or at the expense of veterans who are more likely to be homeless, disabled, mentally ill, prone to substance abuse, etc., isn’t benefiting anyone.

When donning a uniform in a work of protest challenges the image a dictator has tried to manufacture, dissects how one nation responds to another, or raises questions of who’s permitted to wear one (and by extension, who’s excluded from wearing one), these are moments that give voice to groups that are often suppressed. Whether one agrees with it, I think it’s still important to listen.

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]