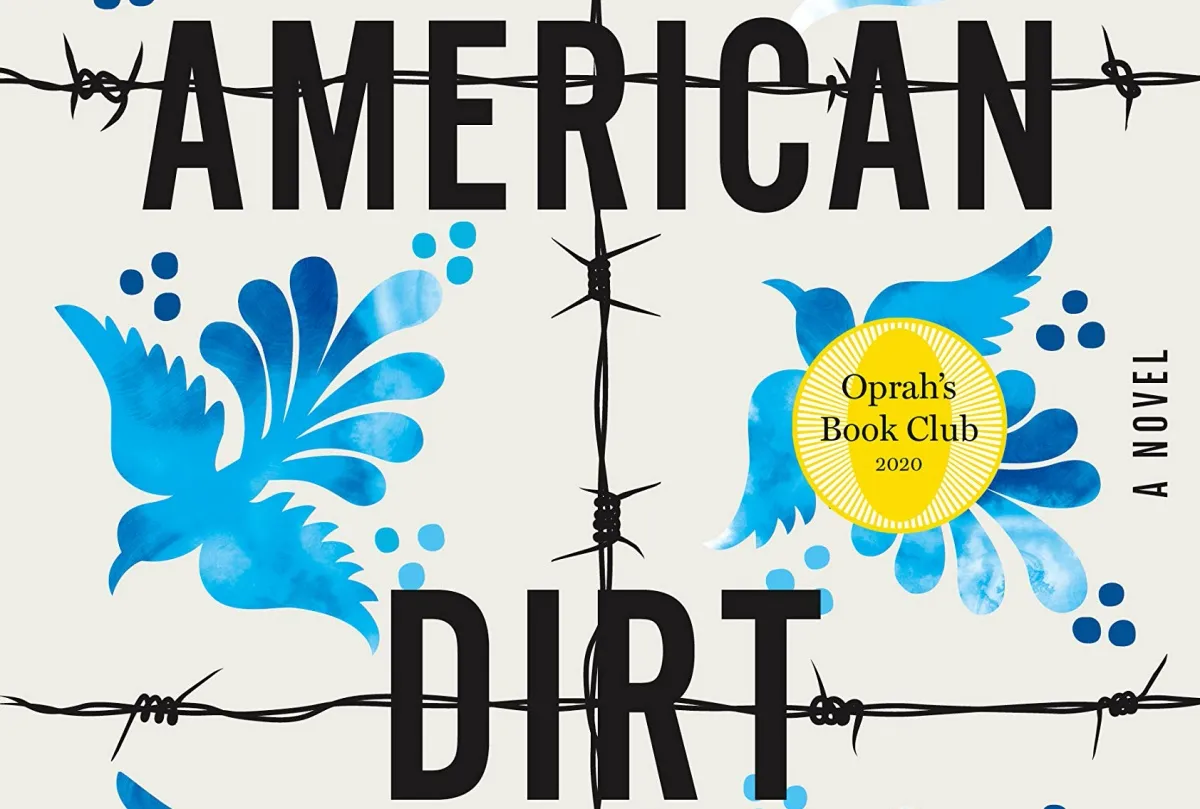

Remember the American Dirt controversy? There was a lot of criticism surrounding the book, its publication, and the resources that went into its creation as well as the promotion of the book. Even though American Dirt was published in 2020, the discourse around this novel is still alive. Years later, the discourse is so alive that Pamela Paul wrote an op-ed defending American Dirt’s legacy.

My problem with American Dirt

American Dirt crossed my radar in the summer of 2019, months before the book came out. At the time, I worked as a bookseller and book reviewer. The marketing pitch I read when I came across this book described it as a fast-paced, multicultural interest and literary fiction.

First of all, fast-paced translates to thriller and I’m not a big fan of the commercial genre. Then there’s the fact that multiple generations of immigrants from multiple nonwhite countries raised me. It makes me resistant to read a book about Mexican immigrants by an author who called herself “white … in every practical way, my family is mostly white.” Plus, books that feel like they exploit marginalized groups’ trauma for entertainment aren’t for me.

This book was an easy pass for me.

One of the first things I learned as a bookseller is to identify the audience of a book. It’s the best way to (you guessed it) sell books. Immediately I recognized this book for white women who enjoy throwing in a thriller in their book club rotation to offset Delia Owen’s Where the Crawdads Sing. This book wasn’t for me, but I knew who to upsell it to when we would inevitably get it in December 2019.

Now that I’m in publishing, I know marketing and editorial departments have extensive conversations about who a book’s audience will be. It’s a large part of the job. I know because I do that every day. So there must’ve been conversations around this title. I would love to overhear those conversations.

But in 2019, I said no to American Dirt, then moved on with my life. Then the discourse came out regarding the expensive marketing, the insensitive barbed wire decoration for the book release party, the author’s generous signing bonus, and more. Essays upon essays were published everywhere and everyone began to critique the publishing industry.

Publishing is white

Paul argues that “publishing, an exciting but demanding and notoriously low-paying job, isn’t for everyone. But it should certainly be open to and populated by people of all backgrounds and tastes. Black editors interested in foreign policy and science fiction, Latino editors interested in emerging conservative voices or horror, graduates from small colleges in the South interested in Nordic literature in translation. People from all walks of life who are open to all kinds of stories from all kinds of authors can bring a breadth of ideas to a creative industry.”

And I agree!

(Although there are plenty of Latinos interested in conservatism, so that’s a moot argument.)

The issue? Publishing is predominately white. I know. I’m in it. I walk the halls of a major publishing house and am usually the only brown person in the room. Salaries are so low most people have their parents supplement their income or have multiple jobs to skate by.

After American Dirt was published, numerous articles exposed publishing for being a predominately white industry. Some of these were anecdotal, but then audits began happening and statistics came out. I was laid off from my bookselling job in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic and turned to freelance full-time. During that time, I started looking and editorial positions because I wanted to champion stories that hadn’t been told. I would be lying if I said the American Dirt scandal didn’t play a role in this decision.

Recently, Pen America came out with statistics Race/Ethnic makeup of overall employees, 2020 new hires, and 2021 new hires. Overall, roughly 65 – 80% of the general employees are white. As someone who exists in the bi/multiracial sliver of Pen America’s pie chart, I genuinely understand what it’s like to be a nonwhite editor and writer in publishing.

Paul writes in a place that feels under attack. Which is odd considering that according to the Guardian, publishing is predominantly 79% white and 78% women. So she is in the majority in our industry.

Tokenism vs Decolonialism

Throughout the NYT piece, certain author names popped up. Some of those who spoke favorably of Cummins were Oprah, Guillermo Arriaga, Sandra Cisneros, and more. These are prominent figures in the art space. Their work is famous and groundbreaking for its time, but sometimes the conversation keeps moving and the artist does not.

Throwing around the word tokenism is dangerous, but I’ll do it. To be painfully clear, tokenism is about marginalized people being chosen by the majority to be the voice of their minority. This moniker speaks less about the person being tokenized and more about the society that tokenizes them. Calling someone special and exceptional exposes the hierarchies and societal expectations for any given nondominant group.

By curating a list of deliberately nonwhite supporters, Paul conveys that those criticizing Cummin are outliers. A loud minority. Yikes, that sounds familiar.

Out of the list, let’s take Guillermo Arriaga. He’s a director and writer born and raised in Mexico City. For those who aren’t Mexican, there’s a racial/ethnic and socioeconomic hierarchy that exists that adheres to the same colorism and racism that exists in America. Mexico isn’t the homogenous society depicted by the American media —especially in books like American Dirt. To get a glimpse, I recommend watching the 2019 Oscar award-winning Netflix Movie Roma. It follows a Mixteco (someone of majority indigenous culture and descent) housekeeper and the upper-middle-class family who employs her. From the look at Arriaga’s green eyes and multiple lucky breaks in various difficult professions to break into, I’d say he belongs to the latter group. So immigrating via coyote probably isn’t something he’s ever considered.

The distinction between the authors listed in Paul’s article that supports Cummin’s work and the over 100+ writers who signed a letter to Oprah criticizing American Dirt is simple. The writers who spoke out are mostly anti-imperialist and whose work is often an act of decolonialism. So, what does that mean in layperson’s terms? It means these writers don’t cater to the white gaze. Their work challenges the status quo by introducing the world to rarely shared or celebrated perspectives.

The main difference between tokenism and someone who practices decolonialism is that one is representative and sometimes reinforces the powers that be, and the other challenges it. The problem with real people being tokenized is that society places them on a pedestal, believing they’re beyond criticism and are the epitome of perfection. When really, they can fall victim to becoming yesmen, which can halt their discourse.

“Reverse racism”

Paul argues that editorial publishing is different now. They have to consider other opinions and lived experiences now. Yikes. How terrible!

One of the actionable solutions to ensure a scandal like American Dirt doesn’t happen again was hiring sensitivity readers. For those who don’t know, a sensitivity reader usually has a certain perspective and edits a manuscript for potentially harmful or inaccurate details. Another solution was taking extra consideration of who should blurb a book. Being mindful of who is involved in the editing process is now taken more seriously. Should everyone reading, editing, and marketing the book have the same background? No, that makes for limited storytelling.

Pushing for more people from different walks of life to be involved with the process is slowly becoming the norm. Paul calls this “self-censorship.” This particular version of censorship and free speech seems awfully familiar to Elon Musk’s Twitter rhetoric.

I don’t know why I have to say this but criticism is not the same as censorship.

One of the loudest and fastest critics was Myriam Gurba, whose piece set the literary internet community on fire. Gurba’s known for her fiery writing style, so that wasn’t new. Yet she was demonized for sharing her opinion as a Mexican American, who, unlike Arriaga, grew up in a society that told her that she was only allowed to fill certain roles based on appearance and race.

History has shown that no matter how much critics, politicians and activists may try, you cannot prevent people from enjoying a novel. This is something the book world, faced with ongoing threats of book banning, should know better than anyone else.

We can be appalled that people are saying, ‘You can’t teach those books. You can’t have Jacqueline Woodson in a school library.’ But you can’t stand up for Jeanine Cummins?” Ann Patchett said. “It just goes both ways. People who are not reading the book themselves are telling us what we can and cannot read? Maybe they’re not pulling a book from a classroom, but they’re still shaming people so heavily. The whole thing makes me angry, and it breaks my heart.

Pamela Paul

While Paul’s discourse never overtly makes this statement, she implies that the criticism behind American Dirt is reverse racism. Here’s the thing … Critics aren’t asking for the book to stop being published. Even when the 100+ writers signed the letter to Oprah, they weren’t asking for the book to be condemned or demonized. All they asked was to remove the Oprah’s Book Club sticker. No one is burning books or asking for people to get fired. All we’re asking is to think carefully and considerately. It’s funny that when marginalized people ask for consideration (at the bare minimum), we get met with resistance.

However, the discourse did not hurt American Dirt’s bottom line. If anything, the press it generated created a hungry audience. After all, the book has been a bestseller for three years. Everyone’s still making money.

Why can’t we have mediocre fiction?

At the end of the day, American Dirt should have been a mass-market paperback that your grandma buys at the supermarket. Paul was right. Cummins took a lot of flack “for not writing a more literary novel.” The thing is, the book was never destined to be a literary masterpiece. It was supposed to be a fun thriller that exploited a “trendy” topic (trendy as in the intended audience isn’t actively worried about someone they know being deported).

Well, it’s hard for fun books to be picked up by publishers if there’s no perceived audience for them. The people in charge of selecting the books and the audience are literary agents and acquisitions editors who are … well, white. Through their unconscious bias, they’re selecting stories that speak to them in ways they’re familiar with. Matthew Salesses writes about this in Craft in the Real World, which challenges Iowa’s Writer’s Workshop and Western literary canon by demanding we expose ourselves to different literary traditions.

Diversity is still relatively new in publishing. Off the top of your head, name a thriller Latine writer. What about an adult Sci-Fi/Fantasy South Asian writer? How about a South East Asian Romance author? I wouldn’t blame you if you didn’t think of Isabella Maldonado, Nalini Singh, or Jesse Q. Sutanto. My niche is intersectional, postcolonial fiction—even commercial fiction. My personal library took decades and various publishing jobs to curate.

We want fun books. We also want to be the authority of our experience. At the end of the day, publishing continues to tell marginalized communities that we have no agency over our stories. We can only exist in the gaze of others—whether it be consumers, editors, literary agents, CEOs, reviewers, marketers, writers, etc. If that’s the case, when those roles are largely white, we can be subjected to dangerous stereotypes that perpetuate false and one-dimensional depictions of us. Oftentimes, especially in America, these fictional depictions are the only representation we get in certain areas of the U.S.

When will we get a chance to tell our stories?

(featured image: Flatiron Books)

Published: Jan 28, 2023 12:13 pm