Did You Catch the Meta Nod of Sintara Golden’s Current Read in ‘American Fiction’?

Based on Percival Everett’s 2001 novel Erasure, American Fiction takes a critical look at the way art by Black writers is shaped by the expectations and whims of white audiences. In addition to framing and dialogue, the film also continues these conversations in subtle ways—including some brilliant unaddressed props.

There’s no person in American Fiction cast as the antagonist. There’s internal conflict, communal conflict, and societal conflict. The latter takes center stage as the story lampoons white liberal institutions fascinated with an imaginary universal Black American experience.

However, if you asked the main character Monk (played by Jeffrey Wright), he would see Black authors like Sintara Golden (Issa Rae) as someone he is working against.

***Spoilers for American Fiction***

Sintara earns critical and commercial success for her novel We’s Lives in Da Ghetto. This gets under Monk’s skin as he sees the book as the epitome of what publishing demands from him and other Black creatives and scholars. His disdain for Sintara’s success and racism in publishing (and entertainment at large) inspires him to write his own book in the same style. To the chagrin of Monk, his book, meant to be insultingly derisive and written in one session and also while intoxicated, is adored by the industry.

White Negroes in American Fiction

In the latter half of the film, Monk confronts Sintara about her writing. Without getting into the specifics of the scene, I love its inclusion in the film. Rae has said that director Cord Johnson craved a face-off between Monk and Sintara. In Everett’s experimental novel, this never happened, but Johnson worked it into the film. It acts as a counterweight to Monk’s sometimes narrow-minded perspective from a Black writer who doesn’t know him through intimate relations like family or courtship.

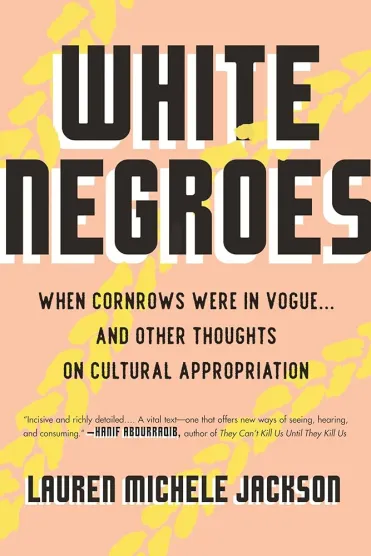

In this scene, Sintara holds one of my favorite non-fiction books of all time. The prop is another book covered to appear as White Negroes: When Cornrows Were in Vogue & Other Thoughts on Cultural Appropriation by Lauren Michele Jackson.

Famous for her articles on culture and Blackness (most ironically pinning down digital Blackface), Jackson constructed this book as a way of reflecting on the tangible harm and lucrative nature of cultural appropriation. Through a series of essays, she tackles this in the art world, pop music, language, food, technology, and more. She even exposes her own missteps into appropriation. A running motif of White Negroes is the desire of many white people (or non-white people with closer proximity to whiteness) to use the aesthetics of their perceived understanding of Blackness.

The inclusion of this book is a brilliant nod to the secondary plot of the film. Monk has his own narrow views of what Blackness is and isn’t. When he takes on the pseudonym Stagg R. Leigh, a convict-on-the-run selling a struggle story, that is Blackness performed. At first, this comes as a middle finger to white liberal establishments, but then to make money—a life-changing amount of money, even for Monk. While he’s aware of his performance, there’s a disconnect between him and other Black people, in part due to class. The childhood maid, beach house, and three-plus PhDs were a dead giveaway of that divide. This is a key factor (next to self-rightness) in why Monk fails to recognize how Black audiences might see something in Sintara’s work.

The scene in which Jackson’s book is present has Sintara confronting Monk over all of this. She defends her right to express an experience some Black Americans have, regardless of its adoration from white folks—which also acts as a pushback against Monk’s attitudes toward race and “Black art.”

Because White Negroes was one of the few books in the film that audiences got a clear view of, its importance is magnified. (Just like that RBG poster in the office of the liberal publisher eating up Monk’s exaggerated lies.) After all, American Fiction centers the publishing world. Yes, American Fiction shows some multiple copies of books in Monk’s agent’s office. Also, We’s Lives in Da Ghetto appears to follow Monk through his life. Yet, we barely get a view of one of Monk’s past works—and he is the main character!

Each book that is clearly identifiable in frame during the film has a purpose. Here, Jackson’s novel acts as almost a third character in one of the comedy’s most tense scenes.

(featured image: Claire Folger/MGM)

The Mary Sue may earn an affiliate commission on products and services purchased through links.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]