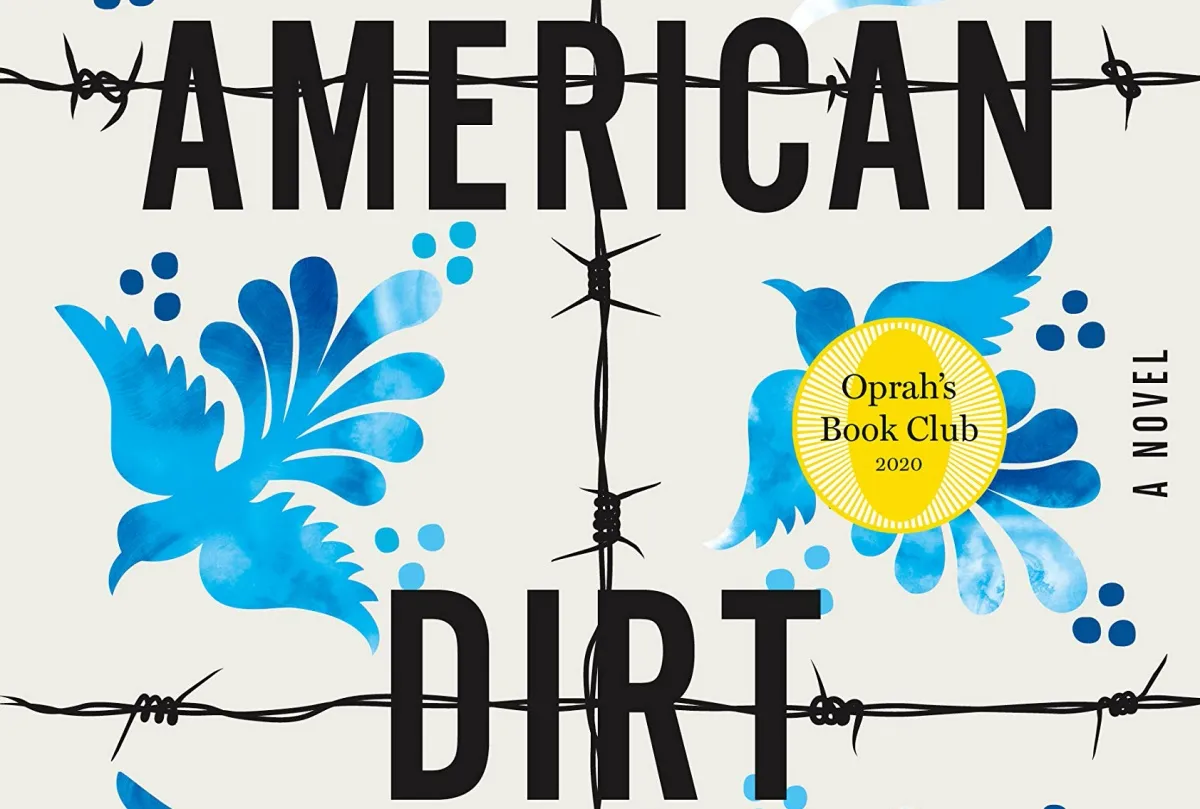

Oprah’s Book Club pick American Dirt was the subject of a lot of controversy due to Latinx outcry about the novel being a negative and stereotypical depiction of what was going on at the border. Author Jeanine Cummins was presented in a way that misinformed audiences about her own identity and the identity of her husband.

Oprah is excellent and, knowing how to spin and handle her brand, used her Apple TV show, Oprah’s Book Club, to address the issue and brought on not just Cummins, but Reyna Grande, Julissa Arce, and Esther Cepeda—all of whom had written pieces critical of American Dirt.

Oprah talked about how reading American Dirt “opened her up” to the feelings of what was going on at the border, and the book was a way to “pierce the consciousness” and create empathy, which is why she picked the book. She made it clear that she believes fundamentally in anyone using their imagination to create whatever they choose, and that silencing one author is essentially a mistake.

So from the outset, Oprah did her best to be diplomatic and defend her choice from the perspective of someone who understands what it is like to be attacked in the public eye.

Cummins says having her integrity questioned was hard, and it pains her to be in the middle of this really challenging conversation—especially since she didn’t expect it. 10,000 galleys were sent out, and yet, right before publication, there was a swell of backlash that was so jarring in comparison to the nearly universal praise that the book was getting beforehand.

The conversation really got interesting and dynamic once the other panelists took the stage—mostly.

Reyna Grande made the powerful point that many Latinx people are told “our stories don’t matter, our stories don’t sell well,” and they are made to feel ashamed of their immigrant experiences, and therefore, they will get rejected or they will be published with little monetary devotion.

Julissa Arce, the author of My (Underground) American Dream, who has one of the most compelling stories, said, “As a Latina writer, I’m often asked to make my stories ‘more relevant’ and to make them more accessible,” which she feels is basically saying make them more relevant to white people. And honestly, that feels really true.

Her issue is with the publishing industry that keeps work that is for Latinx people, especially young children, off the shelves, in favor of books that tug at liberal heartstrings.

Esther Cepeda explained how it’s “hard to swallow” that she has been writing these stories about children dying, mothers, and all of these immigrant experiences, but those stories didn’t touch the hearts of people. The story of a middle-class Mexican woman with money, who gets to live Happily Ever After, did.

At one point, Oprah pulled up a quote from a white reader of American Dirt, who said, “I love that she made me see immigrants as mothers…I was always sympathetic to their treatment, but really didn’t ever think [of] them as individuals. Although I feel ashamed for admitting that, realizing, even more than ever, how I exist in my bubble. At 70, I feel too tired to fight any more, and this has opened my eyes.”

This part, which was meant to show the impact of a book like American Dirt, ended up leaving a sour taste in my mouth. Of course, art has always played a role in exposing and opening people up to perspectives outside of their bubble, and that’s really important. However, with the exception of the Native American population and Black descendants of chattel slavery, every American is here because they are descended from an immigrant—many of them fleeing something.

We all exist in bubbles, absolutely, but isn’t the reason we keep assigning books like To Kill a Mockingbird, The Diary of Anne Frank, and titles like that in middle school is so that children grow up having a sense of empathy for people not like them?

Still, it is the reality. We love narratives that can capture the harrowing experience of marginalized people, but we tend to historically not be as picky about who the person delivering that message is. Hell, just look at one of the most important anti-slavery texts of all time: Uncle Tom’s Cabin, by Harriet Beecher Stowe.

The difference between Stowe and Cummins is that Stowe was blatantly writing for white people. She created the characters to be so hyper moral and pure because it was meant to create empathy. Stowe was also a deeply religious woman, hence all her Christ-like writing of the main Black character, Tom. “The goal of the book was to educate Northerners on the realistic horrors of the things that were happening in the South. The other purpose was to try to make people in the South feel more empathetic towards the people they were forcing into slavery.”

Now, at this point, slavery had been going on for … *counts* … centuries in America—two hundred and thirty-three years, to be exact. Before Uncle Tom’s Cabin was published in 1852, there had been many anti-slavery texts written to generate enthusiasm for the abolition movement: The History of Mary Prince, a West Indian Slave (1831); Life of William Grimes, the Runaway Slave (1825); Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845); Narrative of William W. Brown, a Fugitive Slave (1847); The Life and Adventures of Charles Ball (1835); and any more. Still, none of those autobiographical tales had the impact of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which often gets cited as one of the reasons the Civil War happened.

At the same time, Uncle Tom’s Cabin is filled with stereotypes about Black people and helped popularize a lot of minstrelsy characters. Plus, the book was heavily inspired by the abolitionist and minister Josiah Henson, and Stowe herself had limited firsthand knowledge about Black people before writing the book.

This is why, despite the empathy these writers are trying to produce, while well-meaning, it is often at the expense of jumping over the voices of people within those communities—especially when your privilege allows you to be believed and considered over those communities.

It’s the problem with American Dirt, and it is not a new issue.

Watching the episode, it certainly feels like there are things that were cut and editorialized, but I don’t think it really went as deep as it could have.

As Manuel Betancourt from Remezcla put it:

“[…] this was all a conversation starter. A chance to continue a dialogue. An opportunity to hear from all sides. And yes, that means we even get to hear many an audience member praising the book for doing precisely what Oprah and Cummins had hoped, saying it had moved them and opened their eyes to the plight of its characters. Therein lies the reason why the two-part episode is frustrating to watch: it repeatedly re-centers the conversation in ways that demand readers and viewers be thankful for the controversy altogether.”

(via Remezcla, image: Flatiron Books)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Published: Mar 11, 2020 03:07 pm