Whether it’s a human familiar who has spent a decade serving a Staten Island vampire in hopes of a being turned himself, a troupe of werewolves ready to mark their territory at any cost (provided they aren’t distracted by a squeaky toy), or a soldier of the Ottoman Empire so relentless he was named for his relentlessness, everyone needs characters to whom they can relate—and the FX comedy series What We Do in the Shadows delivers just that.

Based on the 2014 movie of the same name, the series also shares its premise and mockumentary style: a film crew has been granted access (and theoretical protection) to make a documentary about a group of vampires living as roommates. The movie, which was written and directed by Taika Waititi, was set in New Zealand, while the series is series set in the same “world” but follows a different group of vampire characters that live as roommates in New York City.

Among the new characters introduced by the series are Nadja and Laszlo, a husband and wife who are both bisexual: in the pilot, news of the impending arrival of the Baron leads to both Nadja and Laszlo confessing that they each had a sexual affair with the elder vampire in the past.

As might be expected, the arrival of the Baron leads to some drama among the roommates, but unlike many other pieces of fiction, the fact that Laszlo is bisexual is never presented as either a crisis that requires resolution or as the punchline of a joke. The idea of being attracted to the Baron is presented in a humorous light; the desiccated vampire is played by master of inhuman disguise Doug Jones, and the fact that the Baron’s sex appeal falls somewhere between the Pan Labyrinth’s Pale Man and The Shape of Water’s main fish dish is played for laughs.

In the second episode, during a confessional recorded by the film crew, Laszlo and Nadja both lament the Baron’s unfortunate habit of issuing orders related to the vampire takeover during sexual climax. While the joke involves the fact that Laszlo is bi, that detail isn’t presented as intrinsically humorous; it simply serves as an element of the setup: both Laszlo and his wife have a former lover in common. The punchline is derived from the Baron’s unfortunate timing and the difficulty of remembering specific statements whilst distracted by sex, combined with the horrific nature of the Baron’s command to subjugate the entire human race.

The Seminal Impaler

Using vampirism to explore sexual subtext has been an intrinsic element of vampires in pop culture since Dracula showed up in London with a crate full of dirt and an eye on the local plasma selection. In Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula, the eponymous vampire seduces Lucy Westerna (who had previously lamented that she could not marry three men). As a vampire, Lucy is portrayed as a creature unable to resist the urges of her animalistic lust, transformed from a woman of (moderate) virtue into an entity of “voluptuous wantonness.”

It is only after a stake has been hammered through Lucy’s heart that the vampirism is purged and the situation returns to chaste stability, her countenance no longer that of a “foul Thing” but returned to a state of “purity.” To the Victorian sensibilities of Stoker’s novel, any demonstration of sexuality in a woman—even when it’s directed toward a man—is tantamount to demonic possession and must be exorcised before the situation can be resolved.

Once Lucy has been staked, she’s returned to a chastened and “pure” state. While the fact that she’s dead is treated as a tragedy, it also creates a stable situation: although Lucy’s life may be over, at least the memory of her being innocent and non-threatening isn’t endangered by her continued agency.

Buffy and Lestat

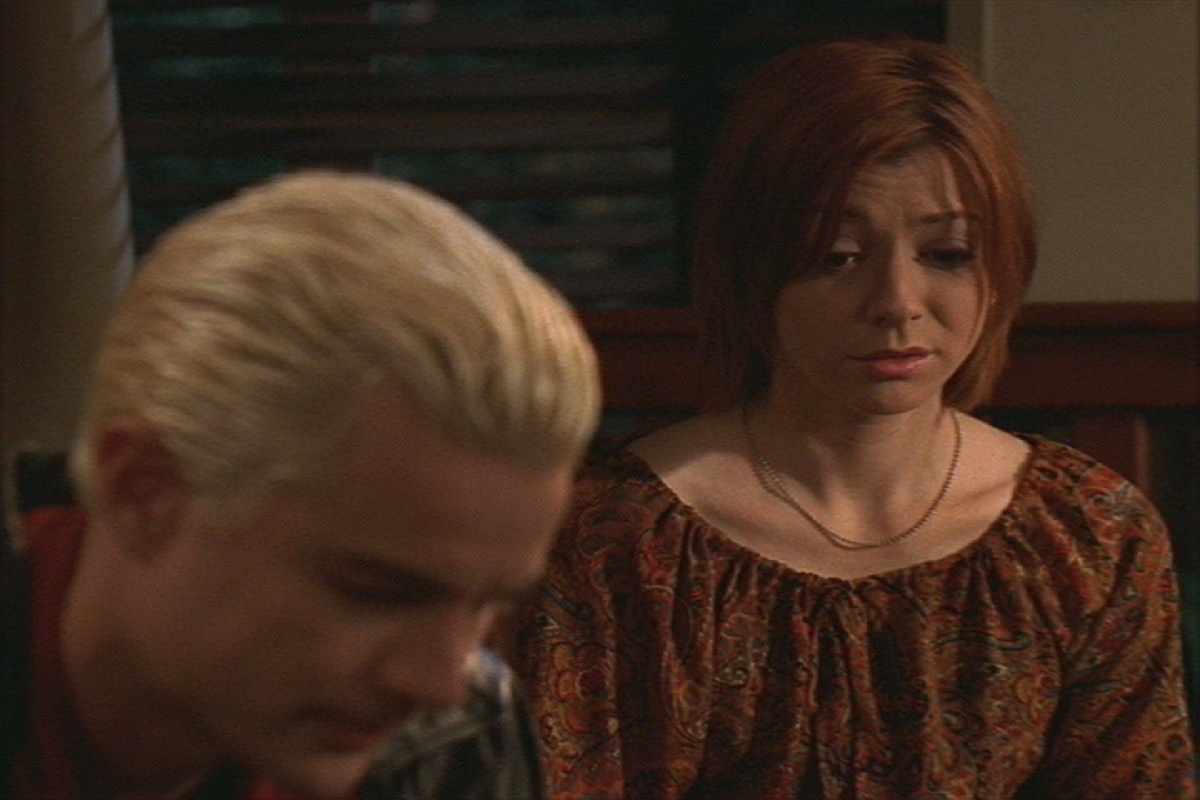

Vampirism has been used to explore issues concerning sexuality in more recent pop culture, as well. In the Buffy the Vampire Slayer season four episode “The Initiative,” Spike deals with the effect of having a microchip implanted in his brain by a shadowy military organization called the Initiative. The chip prevents him from causing any harm to a human by giving him a jolt of pain any time he attempts to attack.

After escaping from the Initiative’s subterranean lab and locating Willow, Spike attempts to bite her, only to find himself unable. The scene deliberately evokes an inability to perform, with Willow assuring Spike that it must happen to lots of vampires and that they could try again when he was more relaxed. The link between vampirism and sexual performance is one the series continues to mine as Spike attempts to rid himself of the Initiative’s implant.

A lack of adherence to societal convention concerning sexuality has also long been a key element of vampires in pop culture. Lestat, the focus of the majority of Anne Rice’s Vampire Chronicles, including Interview With the Vampire, is bisexual, embracing both men and women as lovers over the course of his long afterlife.

Representation of the Damned

But even considering the typical sexual subtext assigned to the vampire in pop culture, should these creatures of the night be considered aspirational? The protagonists of What We Do in the Shadows are monsters, after all, and regularly engage in casual murder and cartoonish acts of violence. As with many depictions of vampires, these horrific actions are frequently blended with sex: after exsanguinating a passerby in the park, Laszlo and Nadja discuss some post-murder coitus. Nadja’s courtship of her reincarnated lover, Gregor, slips from lust to bloodlust faster than a tongue slides over fangs.

Still, much of the show’s humor derives from mining the contrast between the mundane activities in which the vampire roommates engage and the horrific nature of their more classic vampire characteristics. In the first episode, the vampires have a dispute over the labeling of food that will be familiar to many in the audience who have lived with roommates, but the comedy comes from the fact that the “food” that needs to be labeled is the humans kept imprisoned in the basement.

While the vampires on the series are presented as bloodthirsty monsters, the audience is still plainly meant to relate to the characters in spite of their more horrific tendencies. Part of presenting honest queer representation is acknowledging that queer people exist in every context—including questionable role models, like the undead roommates of What We Do in the Shadows.

While the series may be a comedy, it’s clearly self-aware concerning representation: in the pilot, human familiar Guillermo cites Antonio Banderas in Interview With the Vampire as the first time he had seen a “Hispanic vampire” in a mainstream movie, which inspired him to pursue his dream. Guillermo’s desire to emulate Banderas and become a vampire is presented in a tongue-in-cheek manner, but the gag works because it draws upon the real framework of representation.

For those still waiting to see themselves among the undead, there is reason to stave off despair: FX has renewed What We Do in the Shadows for a second season. With Nadja having turned bi LARPer Jenna into a vampire, there’s even a chance a new roommate of the damned may be moving in—and if seeing that’s not worth getting out of your coffin, then what is?

(featured image: FX)

Avery Kaplan is queer trans woman who lives in Southern California with her books and her cats. She and her partner co-authored the forthcoming book LGBTQ Life: Double Challenge, a resource about intersectionality for middle schoolers. For more of her writing, please follow @averykaplan6 on twitter.

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Published: May 10, 2019 09:17 am