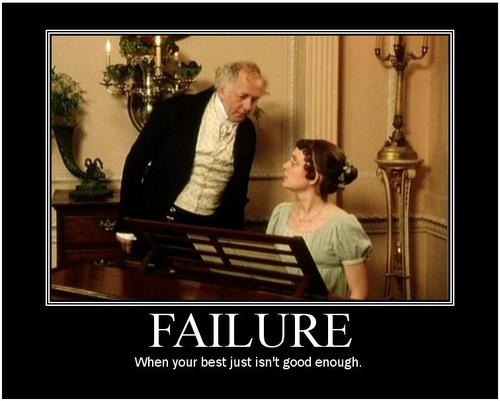

Nine years ago, teenaged me was cast in a tiny role in the local Junior College’s play adaptation of Pride and Prejudice.

As a high school kid in a college production, I wanted to do my absolute best, and though my role was small I was hellbent on doing All The Research. Beyond historical and dialectical work, that included a need to find out how she read in the novel. Unfortunately, the role I was playing was Mary Bennet, and the answer to my curiosity was: not very well.

In my actor prep, I had uncovered a socially anxious, self-conscious girl, who found little to cling to while surrounded by the famed vivacity and beauty of sisters to whom others couldn’t help but compare her. I found a girl who couldn’t fit in if she tried, who had no answers and no friends, and so sought stability and rightness in religion—something that generations of others had already deemed proper, thus freeing her from the responsibility of judging for herself. She seemed familiar to me in ways I couldn’t yet articulate and I hoped that she could be happy.

In the book, I found the same girl, but a very different perspective.

Jane Austen was one of the great observers of humanity. I put her on the same tier as Shakespeare and Victor Hugo in that regard. Where other writers construct a few memorable characters (who are then repeated over multiple pieces), Jane Austen meticulously records small human details, and carefully bestows these individual traits to suggest characters so clearly drawn that they take your breath away with recognition.

Jane Austen was one of the great observers of humanity. I put her on the same tier as Shakespeare and Victor Hugo in that regard. Where other writers construct a few memorable characters (who are then repeated over multiple pieces), Jane Austen meticulously records small human details, and carefully bestows these individual traits to suggest characters so clearly drawn that they take your breath away with recognition.

She creates characters that—200 years later—we have met before, and not just in sweeping archetypical manner. That’s your aunt. Your passive-aggressive college roommate. That’s your brother’s ex-girlfriend, because surely no one else could have that small specific quirk. As they are so 3 dimensional, even the nastiest characters are treated with humanity. There’s something sad about Lady Catherine de Bourgh’s refusal to see her daughter clearly. We have sympathy—in spite of ourselves—for Miss Bingley’s disappointment in her marriage prospects.

All this made her treatment of Mary stand out, because in reading Pride and Prejudice I found no such kindness.

I felt let down by what I perceived as Austen’s heartlessness. She seemed to blame Mary for her isolation and for choosing to be so independent and weird. We are meant to laugh at her. We are meant to catch Mr. Bennet’s jabs at her expense, and we’re meant believe that she is too oblivious and vain to be harmed by them. The disconnect was startling, and I felt there must have been some aspect of Mary’s personality that Austen either couldn’t comprehend, or couldn’t discuss with sympathy.

I kept coming back to this line of Mary’s: “Vanity and pride are different things, though the words are often used synonymously. A person may be proud without being vain. Pride relates more to our opinion of ourselves, vanity to what we would have others think of us.” In addition to being one of the clearest little pieces of morality Mary spouts (in that it could arguably be a thesis for the driving force of the entire book), it’s also one of her only speeches that is not a direct quote from a religious sermon or even all that overtly moralistic. It’s an observation. She’s thought about this.

The line becomes especially poignant if you interpret her as someone with reason to distinguish the two—someone with very good reasons to construct an acceptable image for herself, and have pride in the construction. With religion as an image design manual, she can’t go wrong. Not only is she well-hidden in piety, but she also gets to pretend moral superiority. It’s perfect for keeping others at arms’ length. Interpreting Mary as a lost and lonely lesbian may be a leap based on her limited page time, but it adds poignance to every appearance of an otherwise underwritten and strangely unsympathetic character. And while it’s true that not every character in a novel needs to be fully fleshed out (some characters are only there to provide color or commentary—I know this) it’s exciting to apply the question often asked in theatre production: what’s the more interesting choice?

I’m not a member of the Jane Austen Society of North America, but I have dipped my toes in a few classic literature fan societies, and I can safely say that there is a general squeamishness about queer readings. Certainly there is a reluctance to consider queer interpretations of classic characters as serious in any way. There’s a patronizing consensus among the old-guard that queer analysis was an invention of the 1970s and that it’s a fad that will pass and has nothing to do with the classics or how life was back in them days.

But the fact is, we have always existed. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer people have always been kicking around society; it is inconceivable that Jane Austen would never have met one in her lifetime. And as she was a great observer of humanity it is almost as unlikely that she would never have included a queer person in her writing—whether or not she knew what made them act in such a way.

We know there were contemporaries of Austen who lived relatively openly. Anne Lister leaps to mind, and we only know her story because her diary was so heavily coded that her family didn’t destroy it right away. When the diary’s contents were discovered, one thoughtful relative had the foresight to hide it in the bones of the house for future generations.

How many other stories have been lost? How many were only half told? Who was the grumpy, pedantic, kill-joy that Jane Austen rolled her eyes at parties in Brighton and whose traits she borrowed to create Mary? Was she as lost and alone as Mary seems to be?

Once I saw Mary as a lesbian, she wouldn’t let me go. When I sat down to write something, she was a natural protagonist. An early version of my play had Mary Bennet and Holden Caulfield commiserating over their fictionality, and the fact that they are generally reviled by the living people who read about them. It was bad. Laughably bad. I dropped the thing and did my best to forget.

In the meantime, I wrote some other plays which will never see the light of day, and enjoyed many pastiches featuring Mary as the lead to get my Mary Bennet fix. Most of them end with marriage (this is Austen after all.) Many make her softer and less unpleasantly judgmental to accomplish this, and not a single one of them that I could find interpreted her as queer. However, since I couldn’t see her any other way, I thought how interesting it might be to see my Mary—queer Mary—preparing to wed a man.

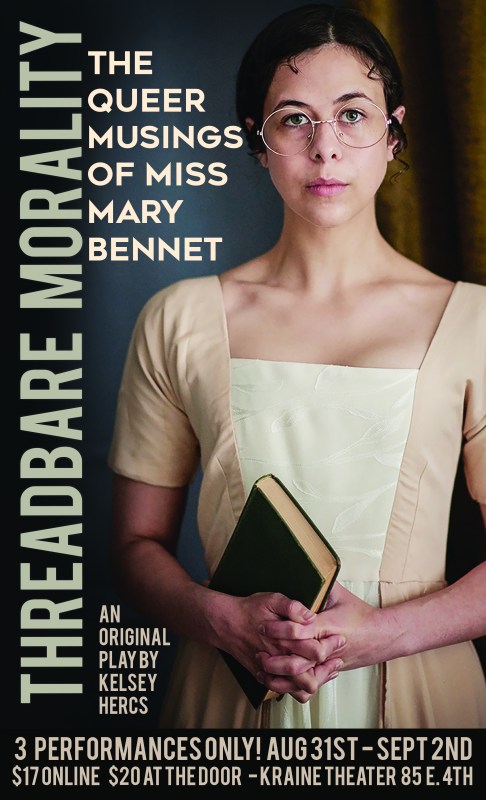

Some of Mary’s musings from the awful “hated characters’ otherworldly green room” play can still be found in Threadbare Morality—such as her assertion that any civilized lady who makes a thoughtful and unbiased study of them can’t possibly enjoy the company of men. But other than borrowing a one-woman-show structure there’s nothing otherworldly about it; it takes place firmly in Austen’s Longbourne.

In my play, it’s been a few years since Jane, Lizzie, and Lydia left Longbourne. According to Austen herself (in letters to her sister), Mary was prevailed upon to mix more often among people when her sisters left, and would eventually marry a clerk (which Austen perhaps saw as karmic retribution for vanity) and become one of the stars of Meryton’s small-town society. I chose to take her words as canon, but couldn’t imagine Mary suddenly loving parties and boys.

Instead, I tried to write a Mary who had matured over the years, but was still just as unforgivingly pious and socially uncomfortable. I tried to imagine what sort of marriage a regency lesbian with no fortune would consider accepting. Especially one who had witnessed all four of her sisters find their ideal matches. I tried to let her find happiness, despite the lexical gaps she finds in relating her experience.

Right now the play is a short one-act with something that technically counts as an ending, and it will be staged in New York City at the end of August. However, I don’t think I’m done with Mary’s story. I think she will have other queer musings to spin, and I don’t think she’ll be alone. I only hope I get to be the one to record them.

You can see Kelsey’s play Threadbare Morality in New York City, Aug 31st-Sept 2nd at the Kraine Theater. Tickets are available here.

(images: Kelsey Hercs, the BBC, BBC2, Focus Features)

Kelsey Hercs is conservatory trained performer whose interests veered slightly to the left into playwriting, comics writing, and burlesque. She creates play in historical settings with queer themes and vows that if she ever kills a queer character, three more will pop up in their place. She has never written a cis straight white guy.

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Published: Aug 1, 2017 04:36 pm