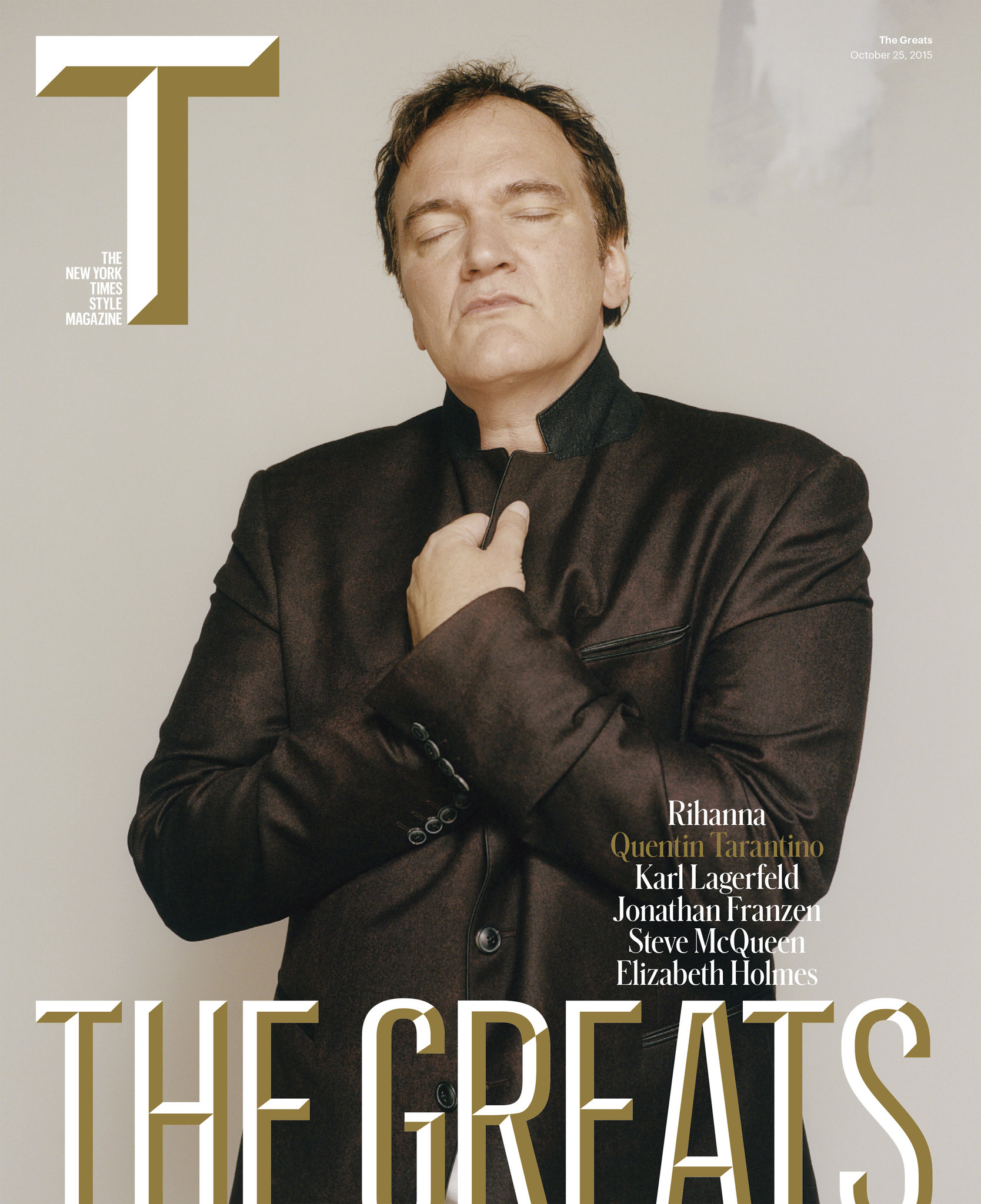

Quentin Tarantino Remains Stuck in the Mid-1990s as World Moves on Without Him

OK, but seriously, what is this pose, though? Is he reveling in his own “genius?” JUST STAND LIKE A FUCKING PERSON, DUDE.

First things first. I love Quentin Tarantino’s films. I’m a huge fan of just about every single one of them, and I love that he seems to revel in giving marginalized groups revenge films. Kill Bill was a woman’s revenge flick. Django Unchained was a revenge flick for black people. Inglorious Basterds was a revenge flick for Jews. However, it seems like Tarantino has missed the train into the new millennium, and remains stuck in the mid-1990s, defending shooting and screening on film, balking at the popularity of television, and seemingly not understanding what current audiences and critics understand – that the internet has allowed movie-going audiences to be more savvy about things like, you know, how we treat each other along lines of race, gender, sexuality, and class.

In an interview that should’ve been called “Two Entitled, Middle-Aged White Guys Get Together to Wank Each Other Off While Not Understanding the World Around Them,” Brett Easton Ellis interviews Tarantino for The New York Times Style Magazine, basically fawning all over the director rather than doing what journalists usually try to do when interviewing – actually probing the director’s material and examining the interplay between that material and the Real World.

In the piece, it becomes clear that, instead of the maverick director, Tarantino has become the old, befuddled fuddy-duddy telling us all to get off his lawn. Or perhaps it’s Ellis, the also formerly maverick author of books like American Psycho and The Rules of Attraction, who’s holding the opinions, as the piece has very few actual quotes from Tarantino – probably because Ellis was so busy fanboying out, he forgot to record any.

Here’s what Tarantino/Ellis have to say about TV:

We talk about the differences between TV and movies, and how TV relies on a kind of relentless storytelling whose main job is to constantly dispense information, while movies depend much more on mood and atmosphere — TV is a writers’ medium and movies are a directors’ medium. Even in the Golden Age of Television, the notion of TV as art is now considered something of a media-made joke that is finally being publicly deconstructed by critics, journalists and showrunners alike. The best TV shows still have sets that look a little ragged and threadbare because of the reality of TV economics — and to Tarantino this matters. The bigness of his recent movies — ‘‘Inglourious Basterds,’’ ‘‘Django Unchained’’ and now ‘‘The Hateful Eight’’ — feels like a rebuke to the smallness of TV and its increasing relevance to audiences, a fight against watching a series of medium shots and close-ups on your computer, your iPad and your iPhone. The belief in visual spectacle is part of Tarantino’s message in the era of Amazon, Hulu and Netflix.

“TV relies on a kind of relentless storytelling whose main job is to constantly dispense information.” For such a big fan, Ellis clearly has never listened to Tarantino’s dialogue, like, ever. Bill opining on Superman just to allow his truth serum time to take effect on Beatrix Kiddo while ham-fistedly making a connection to her “secret identity” as an assassin? Not only does Tarantino info-dump, but he info-dumps stuff we don’t even need. And this commentary on TV as art being a “media-made joke” is really ill-informed. Especially since films have long since stopped being art the way they used to be. Sprawling vistas alone do not art make.

The most telling statement is this: “TV is a writers’ medium and movies are a directors’ medium.” What these two fail to understand is that things like the Internet have made us care a bit more about actual ideas and substance, and less about images and things “looking cool.” Ideally, a film should do both. I would argue that the reason why audiences have flocked to television is precisely because it is a writers’ medium, and audiences are now savvy enough to be able to discuss the ideas in a piece, rather than simply look at them as “well-constructed.” As creative as Tarantino is, and as fun as his films are, and yes, as specific and stylized as his stories are, I don’t think he’s given the ideas in his films, or how those ideas might be received by a viewing audience, the kind of intense thought he gives his fight scenes, or his efforts at homages to other, earlier films. And I think this is a mistake.

Here’s what Tarantino/Ellis have to say about black critics and political correctness:

As hugely influential as his earlier movies were (there seemed to be thousands of terrible rip-offs throughout the ’90s and into the 2000s), it’s impossible now to imagine an earnest 20-something millennial dreaming up a film as perverse and lurid as Pulp Fiction or Reservoir Dogs or anything else he’s made. In an era obsessed with ‘‘triggering’’ and ‘‘microaggressions’’ and the policing of language, the Tarantino oeuvre is relentlessly un-PC: His movies are impolite, rude, irresponsible and somewhat cold. And the further Tarantino goes, the larger his audience gets, as seen with his racially explosive comedy-western Django Unchained. The Hateful Eight, which takes place eight or nine years after the Civil War, also ended up addressing issues of race, even if this wasn’t his original intention: ‘‘It was just this cool, neat, genre scenario.’’

We touch on this year’s Oscars and the supposed Oscar snubbing of Ava DuVernay’s Martin Luther King movie Selma, which caused a kind of national sentimental-narrative outrage, compounded by the events in Ferguson, and which branded the Academy voters as old and out-of-it racists — despite the fact that 12 Years a Slave had won Best Picture the year before. Tarantino shrugs diplomatically: ‘‘She did a really good job on Selma but Selma deserved an Emmy.’’ Django Unchained, with its depictions of antebellum-era institutionalized racism and Mandingo fights and black self-hatred, is a much more shocking and forward-thinking movie than Selma, and audiences turned it into the biggest hit of Tarantino’s career. But it was also attacked for, among other things, being written and directed by a white man.

Such controversy is not new to Tarantino. ‘‘If you’ve made money being a critic in black culture in the last 20 years you have to deal with me,’’ he says. ‘‘You must have an opinion of me. You must deal with what I’m saying and deal with the consequences.’’ He pauses, considers. ‘‘If you sift through the criticism,’’ he says, ‘‘you’ll see it’s pretty evenly divided between pros and cons. But when the black critics came out with savage think pieces about Django, I couldn’t have cared less. If people don’t like my movies, they don’t like my movies, and if they don’t get it, it doesn’t matter. The bad taste that was left in my mouth had to do with this: It’s been a long time since the subject of a writer’s skin was mentioned as often as mine. You wouldn’t think the color of a writer’s skin should have any effect on the words themselves. In a lot of the more ugly pieces my motives were really brought to bear in the most negative way. It’s like I’m some supervillain coming up with this stuff.’’ But Tarantino is an optimist: ‘‘This is the best time to push buttons,’’ he says a few minutes later. ‘‘This is the best time to get out there because there actually is a genuine platform. Now it’s being talked about.’’

First of all, I could do without the condescending tone about Ava DuVernay’s work. In the piece, Tarantino also makes a resigned, condescending comment about Kathryn Bigelow winning for The Hurt Locker and beating him out for Best Director. Of course, it doesn’t occur to him that there are people who actually believed Bigelow’s film was better than his. He implies it’s because they’re women that people care. Or as Ellis puts it in his tone-deaf commentary, “national sentimental-narrative outrage, compounded by the events in Ferguson.” While, yes, it is thrilling that Bigelow was the first woman to win Best Director, the facts are that 1) The Hurt Locker was considered by many to actually be a great film, and 2) the point is that we shouldn’t have to get this excited when individual women win stuff. Because there should be as many female directors to choose from as there are men. But, of course, Tarantino can’t seem to see beyond his own career.

DuVernay did something in Selma that Tarantino could never do – which is be subtle. Selma didn’t hold back with regard to the violence people experienced during that protest, but it was also amazingly choreographed and done respectfully. The violence in Selma wasn’t supposed to be a spectacle. It was supposed to be a reminder of how people were beaten and killed then, and they’re still being beaten and killed today. DuVernay used a historical story to connect to the world of today and start conversations, which is something that great films should aspire to do. Tarantino thinks that the exploration of race during the Civil War in the upcoming Hateful Eight was “just this cool, neat genre scenario.”

Django Unchained was shocking, and I would say that the violence in it was necessary, but it certainly wasn’t “forward thinking.” We know Mandingo fights may have happened. And, while it was really compelling to watch Samuel L. Jackson’s portrayal of a slave’s self-hatred, that’s not new either. Hell, there’s a reason why people use the term “Uncle Tom.” It’s because novels and writing talking about these things already existed and have already been discussed. This film taught us nothing new, and while it might have supplied a great revenge fantasy for black people, that’s all it did. It didn’t make us think beyond the movie theater except to be like “OMG, that was so gross, right?!”

And that’s the difference. That’s why skin color matters when writing certain stories. For a black person (or for any person of color) the blood loss is a tragedy that needs to be treated with respect. For a white filmmaker like Tarantino, the blood splatter is mere spectacle, employed to make a film “cool,” and so he can’t be troubled with things like the kinds of ideas he’s helping to spread and examine in the wider world – because “cool” seems to be his highest priority. Which is fine, I guess, but don’t be shocked when your audience, increasingly concerned with ideas and broader issues, take you to task.

What Ellis and Tarantino need to understand is that the things that are shocking and progressive to them are things that much of the world has already had to live with and examine for centuries. It’s only now, as the Internet has given us all the power to organize and dissect ideas that white, straight, cis male creators are seeing that discussion be amplified – and it must be frightening for them. These types of discussions are only ever dismissed as “political correctness” by the privileged group who doesn’t have to worry about certain things. For others, these conversations are extremely important, and what is art if not a way to communicate and have conversations?

And I’m not in the camp that says that able-bodied, straight, cisgender white men can never write characters of color, or women, or disabled characters, or trans characters. But when they do, they should do so thoughtfully. They should be smart about it and get input from the community they’re writing about. And since no community is a monolith and thinks the same things are not offensive, be prepared to have those conversations in a non-defensive way. As an artist and a creator in the 21st Century, that’s your job. You’re being held up to a higher standard by people who are more educated and savvy about issues beyond pop culture – deal with it.

Mr. Tarantino, I’m a big fan, but if you’re not prepared to actually delve into your work and talk about it and examine it with your audiences in a thoughtful way, perhaps you shouldn’t be making films anymore. Maverick, mid-1990s Tarantino was great, and was all sorts of groundbreaking. What I’d like to think is that you’ve since grown up enough to be able to have nuanced conversations with people who may be critical of your work for valid reasons that go beyond film. I’d like to think that you’ve grown up enough to see the world beyond the films you make. Have you? Or are you simply looking for excuses to go on doing what you’ve always done without being challenged?

(via Jezebel)

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]