2012 was a big year for Joss Whedon. Buffy the Vampire Slayer had its 15th anniversary, his Avengers brought the Marvel Cinematic Universe together, and on top of everything else, the little indie horror movie he had cowritten with his protégé Drew Goddard, Cabin in the Woods, was finally released. I was fourteen and incapable of talking about anything other than Joss.

My family and I had watched Buffy religiously the summer before, at one point consuming the entire fifth season in a week. I saw myself in so many of his characters. Eventually, when I started screenwriting myself, I would draw heavily on his style. To this day, textbook Whedonisms tend to pop up in my writing—banter in dangerous situations, people masking their pain with humor, the invention of words like “wiggy.”

There was no doubt in my quip-obsessed 9th-grade mind that Joss was a feminist. “In fact,” I thought, “he might be like … an even better feminist than me.” I didn’t know before I watched Buffy that female desire could be portrayed as something so dark, aggressive, and complex—that girls could fight monsters without being laconic, scary grownups like Charlie’s Angels or Lara Croft. Buffy Summers projected strength, vulnerability, and dark, twisted sexuality all at once, something I didn’t know women were allowed to do on television.

Cabin in the Woods was a little too scary for me to see it in theaters at the time. As a consolation prize, my mom bought me one of those glossy, special feature books that also included the complete script. I read little else for months. The dialogue, rhythmic like music, was nothing new to me, but the screen directions? They were magical. When I finally watched the movie, I saw them silently enacted—the funny, subversive voice of Joss and Drew speaking even when the characters weren’t. I didn’t question anything they were telling me.

Those screen directions include this description of Jules, the “dumb blonde” who dies first in the film: “She pops [her shirt] open, holding it together coyly for one moment before pulling the bra off, revealing her breasts, a sheen of sweat (and the fact that they’re not fake) making them all the more enticing. She smiles knowingly, a vision of hedonistic perfection.”

My fourteen year old self learned two important lessons from this description:

- My breasts should be “enticing” but not “fake.”

- Something can’t be misogynistic as long as it’s parody.

Of course, Jules isn’t actually “dumb” and isn’t actually blonde. She dyes her hair at the beginning of the film, and a shady government agent pipes a chemical into the dye in order to slow down her cognition. So, when a rusty trowel nails her hand to the ground as she climaxes, it’s parody. When a zombie throws her decapitated head into the arms of her horrified friend, it’s parody. The writers describe her breasts in detail in the name of parody. Right?

I was really young when I read that script. I felt younger than a lot of fourteen-year-olds. I hadn’t been to many parties or kissed a boy. It didn’t occur to me, then, that Whedon and Goddard didn’t have to write in that specification about Jules’ breasts in order for the screen direction to be effective, or that part of me felt betrayed by these men I revered and trusted.

The script goes to lengths to make Jules’ death feel okay for the audience in the moment. First of all, she’s not a person, she’s a “hedonistic vision of perfection.” It says so right there in the screen directions. Second of all, we can look on self-righteously as the callous agency members watch Jules’ demise, judging them while at the same time enjoying this voyeuristic pleasure ourselves. There’s one more element to this smartly-crafted double-blind which transforms it into a triple blind: Jules isn’t the audience insert, and therefore never inspires anything in the viewer other than detached sympathy.

Audience members, especially Whedon fans, will much more likely identify with Marty, the sarcastic stoner who sees all, or Dana, the awkward, quiet protagonist of the film. The Jules/Dana dichotomy does not go unexplored in the narrative. As they do with so many slasher film tropes, Goddard and Whedon walk the line between commenting and condoning.

At the beginning of the film, we are supposed to take note of the fact that Dana and Jules do not yet embody the virgin/whore archetype: Dana is just getting over an affair with a professor. Jules is sexy and dating a jock, but the screenwriters make sure that we know she is pre-med. As the film moves forward and the evil government agency begins to work its magic, the dichotomy solidifies. Dana becomes more self-conscious and shy, and Jules transforms into a male libido-fueled fantasy. She dances more sexually than anyone is comfortable with, and iconically makes out with a taxidermied bear head during a game of Truth or Dare.

At fourteen, I could draw a distinct line between pre-cabin and post-cabin Jules. Pre-cabin Jules was someone I could be friends with. Post-cabin Jules was scary. She danced like a stripper and made out with a gross bear. My affection for her waned just in time for her to die. Once she did, I still had Dana, who was shy and awkward around boys, just like me.

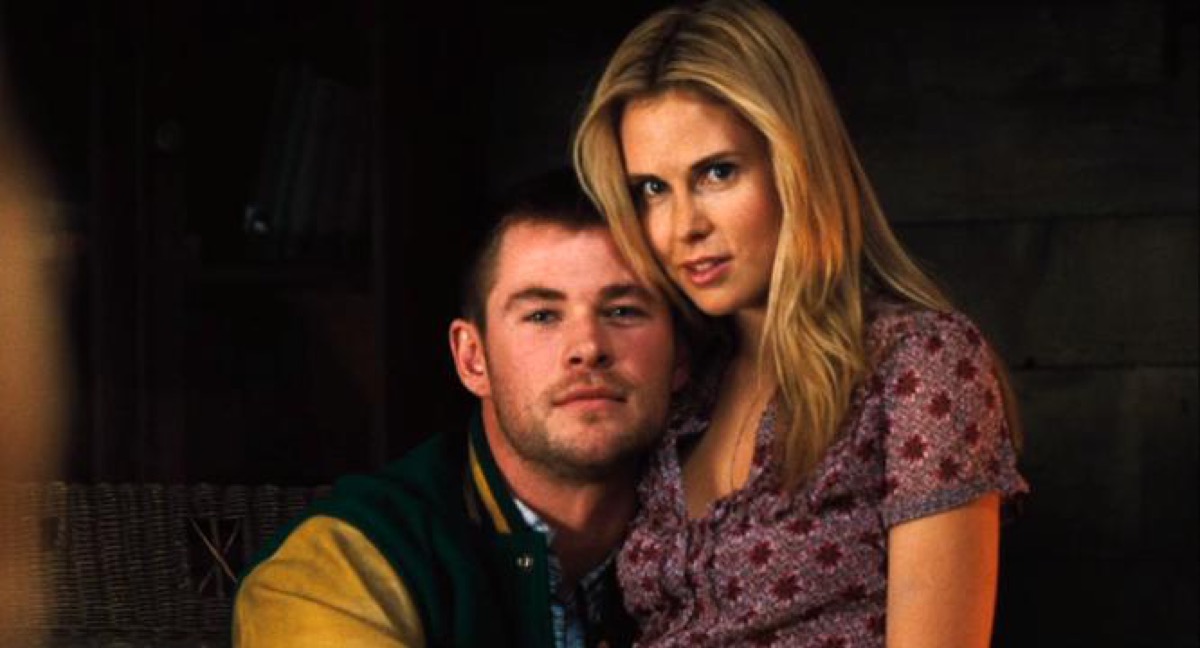

At twenty-three, I have realized that things aren’t as simple as Whedon would like them to be. Watching the movie now, I don’t see much wrong with post-cabin Jules’ behavior. She’s maybe overstepping her friends’ boundaries a little bit, but honestly, the bear kiss is kind of awesome. Her decision to steal into the forest for a midnight rendezvous is also framed as a terrible idea, but honestly, who wouldn’t risk some awkwardly-situated poison oak in order to make out with Chris Hemsworth?

Marty confides in Dana that Jules’ behavior is freaking him out because she’s not acting like herself. To Whedon and Goddard, it’s inconceivable that a woman could be pre-med and prone to lap-dancing, a good friend and a bear-kisser, alive and a hedonistic vision of perfection. Of course, all the characters end up falling into these outdated archetypes; that’s the point. And everyone dies. That’s the point, too.

But in my opinion, no one endures the same humiliation as Jules, who is dragged screaming from the clearing with her breasts still exposed, and decapitated offscreen. I was too young to realize that a woman could be as much Jules as Dana, that Jules’ death was as destructive an image to me as it was to popular blonde girls.

Again, Cabin in the Woods has a really tight script and does a neat job justifying this nudity and violence that might otherwise be considered gratuitous. As Hadley and Sitterson, the men behind the curtain at the agency, root for Jules to take her top off on a gigantic screen, Truman, a noble newcomer, asks them if their behavior, or Jules’s nudity, is really necessary to the operation. Hadley gently chides Truman for his naiveté. “We’re not the only ones watching, kid,” he says.

“Got to keep the customer satisfied,” Sitterson adds. “You understand what’s at stake here?”

Like so much of Joss Whedon’s work, Cabin involves its viewers in a clever extended metaphor. Whedon and Goddard are Sitterson and Hadley. The movie playing onscreen is … well, the movie. We, the audience, are the hungry gods underneath begging for objectification and misogyny in our entertainment. When I was fourteen, I thought that glibly drawing attention to this age-old pattern was the same as changing it. I don’t think that anymore.

One could argue that it’s not the responsibility of films to change the culture in which they are made, but Joss Whedon made his name by calling himself a feminist, creating work that promised not just to comment on the misogyny in film and television but to dismantle it. That’s the most frustrating part of this whole thing to me: so much of Joss Whedon’s writing does what Cabin in the Woods refuses to, transforming toxic narratives rather than just cleverly pointing out how they work.

I don’t just mean that first scene in Buffy where the cute girl in the plaid skirt turns out to be the vampire, but the one where Willow’s anger at the world transforms her into a different person, where Spike discovers that the real, imperfect Buffy beats any of his puerile fantasies, where Buffy sacrifices her own life not for a man, but for her sister. I don’t think that the Cabin in the Woods screen direction is necessarily a mark of underlying lasciviousness or ill intent towards women. Rather, I think it’s a result of complacency.

Cabin isn’t a “feminist” film in the same way Buffy is a feminist show. Therefore, Whedon doesn’t see a need to subvert sexist tropes in the same way. Besides, he and Goddard are still drawing attention to how fucked up those tropes are, right? They really have become Hadley and Sitterson—smart men cracking jokes about a cruel, damaging system without ever reenvisioning it.

I can analyze Whedon’s failings till the undead cows come home (not only in Cabin but in his Avengers work, that infamous Wonder Woman script, and more), but I’ll never stop loving his work. That’s part of the reason I want so much for him to redeem himself in some way, even though I have no idea what that looks like. So much of the “cancel culture” discourse centers around redemption. What could someone like Whedon do to make up for the misogynistic undertones, and sometimes overtones, in his work? Is there any making up for it? I wish I knew.

I keep thinking about the ending of Cabin. Dana has a choice—kill her friend Marty and save the world, or say “fuck you” to the system and let it all burn down. Fed up and bolder than she was at the beginning of the film, Dana chooses the “fuck you” option. The movie ends awesomely, with Marty and Dana holding hands as the Earth splits apart. It’s smart, funny, and designed to make nerds like me go, “Hell yeah,” but I also think it could serve as a blueprint.

Hollywood isn’t exactly cracking open, but there’s certainly been a lot of upheaval lately. Whedon doesn’t have to look any further than his own character for guidance. She aids and abets the destruction of a system that benefits her, steadies herself as the Earth splits open, and marvels at the emergence of a new world.

(images: Lionsgate)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Published: Jul 30, 2020 05:26 pm