TVTropes, which is responsible for me once trying to use the term “Lampshading” in everyday parlance (which didn’t go so well), has a useful term for when characters act in unexpectedly stupid and nonsensical ways, creating unnecessary conflicts in a given television episode or movie where any misunderstandings all could have been worked out through simply communicating properly: the “Idiot Ball.” As the site so succinctly puts it: the Idiot Ball is in use when “a character who is at least competent starts acting stupid for the plot.”

Now, we don’t know the scientist characters in Morgan going into the film, but we certainly are meant to recognize the type: highly intelligent white-coats who grow too attached to their artificially-created and modified human experiment and compromise their objectivity, allowing their smallest problem to escalate into a violent catastrophe in seconds. In that sense, the archetypes of these scientists are familiar enough that their behavior throughout Morgan’s narrative could be considered an experiment in treating the Idiot Ball like a beach ball at a baseball game—it bounces around and around from one character to another, causing these apparent geniuses to take perhaps the least logical or helpful action in any given scenario.

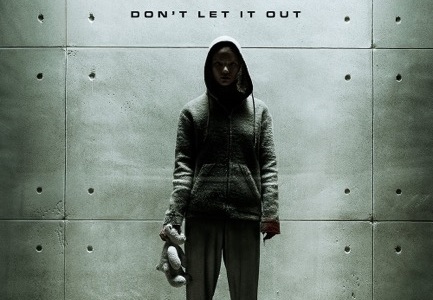

Alex Garland’s Ex Machina, which explored questions of whether artificial intelligence can have not only emotions, but independent will and personal agency as well, was a fantastic film—one of the best of 2015. Morgan, directed by Luke Scott (son of Ridley, who co-produced), wants to be Ex Machina, swapping the AI Ava of Ex Machina for a lab-grown, vaguely-enhanced human child named Morgan (Anya Taylor-Joy) and posing similar questions to the audience, with the added bonus of a bit of action. In that regard, however, Morgan fails spectacularly, trading subtlety, nuance and, frankly, good acting for obvious setups and uneven performances across the board that had me rolling my eyes in my seat. The basic premise of Morgan has no shortage of potential: after Morgan attacks one of her scientist handlers, Lee Weathers (Kate Mara), a risk assessor from the corporation that funds the researchers who created Morgan, is sent to the research facility to assess the risk of Morgan’s existence versus the corporation’s financial aims. Yet, as the cinematography, score, and behavior of the scientists refuse to let us forget, things are not quite as they seem—with Morgan, with the scientists, and with Lee herself.

Despite the warning signs of unevenness in Morgan from the beginning, and some truly unnatural and unsubtle acting from Boyd Holbrook (who plays the facility’s “nutritionist”), Michael Yare (who plays the facilities manager) and Rose Leslie (a behavioral specialist on the team), the film manages to actually create some suspense leading up to the moment Lee and Morgan first meet. As Lee and the inhabitants of the facility sit around the dinner table, we as the audience can see the stirrings of what might have been a more promising direction for the film to take: the scientists all speak adoringly of Morgan, who is five but looks like a teenager and is incredibly precocious, while Lee gets off on the wrong foot by insisting that Morgan is not only an “it,” not a “she,” but that Morgan has no rights, since she is not technically a person. And when Morgan undergoes a psych evaluation by a blustering doctor (Paul Giamatti as a one-scene wonder), we all know that something is going to go horribly wrong, yet the scene has a wonderful tension between Taylor-Joy and Giamatti that is lacking in the rest of the film. But once Morgan has another violent episode and is sentenced to be terminated by the scientists, whom Morgan sees as family and friends, Morgan ceases to act on any of the interesting ideas from earlier in the film, simply becoming a generic, bloody thriller as Morgan takes her revenge on the scientists who forsook her so easily.

The problem with Morgan, again, lies in the Idiot Ball behavior of nearly every character in the movie, but also in the utter lack of basic logic present in each scene, which is conveniently used to make Morgan’s eventual rampage all the more feasible. For example: why are there no bodyguards on the property, if Morgan has the potential to be dangerous? Why do the scientists allow Paul Giamatti’s doctor in the same glass enclosure with Morgan with no backup, safety precautions, or ways to defend himself in case Morgan loses control? Why does Giamatti’s character insist on provoking Morgan incessantly and cruelly, knowing full well Morgan is dangerous, when he’s apparently the best in his field? When Michelle Yeoh’s character, the lead scientist whom Morgan calls “mother,” insists to her reluctant colleagues that Morgan must be terminated, why does she leave the lab before the job is done? Each silly decision is testament to why showing, and not telling, is so necessary when creating any work of media; we are led to believe that these researchers are incredibly smart, yet repeatedly make fools of themselves in order to further the plot.

Morgan also ends with an incredible amount of unanswered questions that make it seem as if the screenwriter hoped that no one would notice how much is not addressed during the film’s 92 minutes. To name but a few: why is the mysterious corporation even funding this kind of research? What was the purpose of Morgan’s creation in the first place? What was the nature of the Helsinki Incident, which is sketched lightly and ominously at the beginning of the film and is not mentioned ever again? Why is Morgan referred to as having “precognition,” a skill which is never used during the course of the film? Not to mention the actually interesting questions a film like Morgan or Ex Machina could actually be addressing in some way: can Morgan love? Can Morgan experience emotion, or merely perform it? Can Morgan be considered a human being? And what place do corporations have in funding this kind of research—in creating, molding, and controlling an enhanced human life for mysterious purposes?

The unabashed positives of Morgan are few and far between, Anya Taylor-Joy’s performance being one of them. Despite being in some truly cheap-looking, unfortunate and downright unnecessary silvery makeup, Taylor-Joy’s physicality and comportment make her fascinating to watch. She manages to play this underwritten role in an eerie, uncanny-valley sort of way that nonetheless garners the audience’s sympathy. When she faces off with Paul Giamatti’s character during the psych evaluation sequence, she and her quiet, magnetic presence hold their own against Giamatti’s decades of experience and naturalistic acting. Additionally, the film’s visuals, while oppressively obvious and pedantic throughout, are quite lovely—the facility is located in a woodsy landscape that is shot very evocatively, when not obscured in part by cliched, sinister fog.

Regrettably, the rest of the performances—and the film itself—are not on the same level. Kate Mara tries to bring some kind of life to what turns out to be a very strange and mysterious role, and her interactions with Morgan are chilling in their own way, but ultimately nothing worth writing home about. Talented actors like Michelle Yeoh, Vinette Robinson, Jennifer Jason Leigh, and Toby Jones are utterly wasted on such thinly-written, one-note characters. Morgan’s score is anything but subtle—the music in each scene broadcasts exactly how we as the audience is supposed to feel, which is varying levels of creeped-out, apparently. And the inevitable twist/shocker ending, which worked so well in Ex Machina, feels underwritten and also, oddly, overly-prescribed as the film nears its conclusion, and doesn’t serve to make any of the preceding ninety minutes make any more sense.

For a film that is ostensibly about a being with almost supernatural intelligence, Morgan is just not that smart, and requires such a suspension of disbelief at times that it’s not worth the effort to try and puzzle out why things are happening the way they are. And it’s quite a shame, too: the cast of the film is talented and diverse and balanced evenly between men and women, and pretty much every single scene passes the Bechdel Test. Yet Morgan is a letdown every step of the way.

images via 20th Century Fox

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

Deborah Krieger is a freelance arts and culture writer and nascent art/media historian and curator. She can be found at i-on-the-arts.com.

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google+.

Published: Sep 13, 2016 11:26 am