Long before I ever played The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past, I read it in the issues of Nintendo Power magazine.

I don’t mean that I read about it, though I undoubtedly encountered coverage of the classic game on those pages. I liked Nintendo Power in the ’90s because it brought a game’s world alive for me when I wasn’t able, as a kid with little pocket money, to explore it for myself. I’d sit with the maps splayed open in front of me, looking at the game screen by screen to learn its secrets, admiring the illustrations in the margins. I imagined myself running and jumping through those lands.

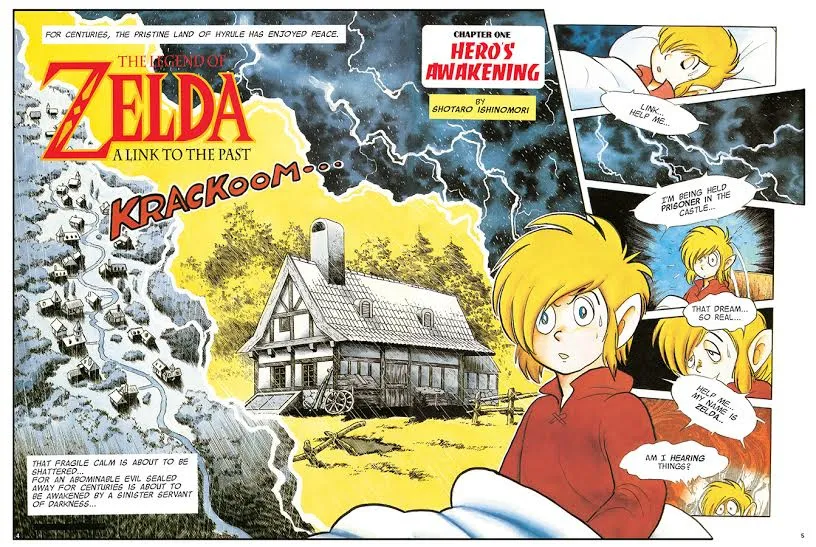

The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past was different. It was The Hot Game, for one, and it came out on the Super Nintendo (SNES), which I didn’t own. In 1992, Nintendo Power devoted several pages of its magazine space to a comic strip adaptation written and illustrated by Shotaro Ishinomori, a prolific comic book creator from Japan who entered the Guinness World Records in 2008 for “most comics published by one author” (more than 770 stories in 500 volumes of manga). There’s a whole museum in Japan about him.

The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past was different. It was The Hot Game, for one, and it came out on the Super Nintendo (SNES), which I didn’t own. In 1992, Nintendo Power devoted several pages of its magazine space to a comic strip adaptation written and illustrated by Shotaro Ishinomori, a prolific comic book creator from Japan who entered the Guinness World Records in 2008 for “most comics published by one author” (more than 770 stories in 500 volumes of manga). There’s a whole museum in Japan about him.

That, and the Super Mario Adventures comic strip that Nintendo Power also published, were my favorite things in the whole magazine. And now it’s back in print, this time courtesy of Viz Media’s Perfect Square imprint.

I couldn’t play A Link to the Past, so the comic was my Let’s Play, my Twitch. I had played Zelda II: The Adventure of Link on the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) and wanted to see more of the green-clad hero in everything and anything I could get my hands on.

Ishinomori’s comic was my ticket into Hyrule. A Link to the Past was bigger and better than Zelda II in every way—at least, that’s what the pages showed me. Players at the time were struck by the size of Hyrule and how it spanned not one world but two: of light and darkness, mirror images yet opposites in their depictions of Hyrule.

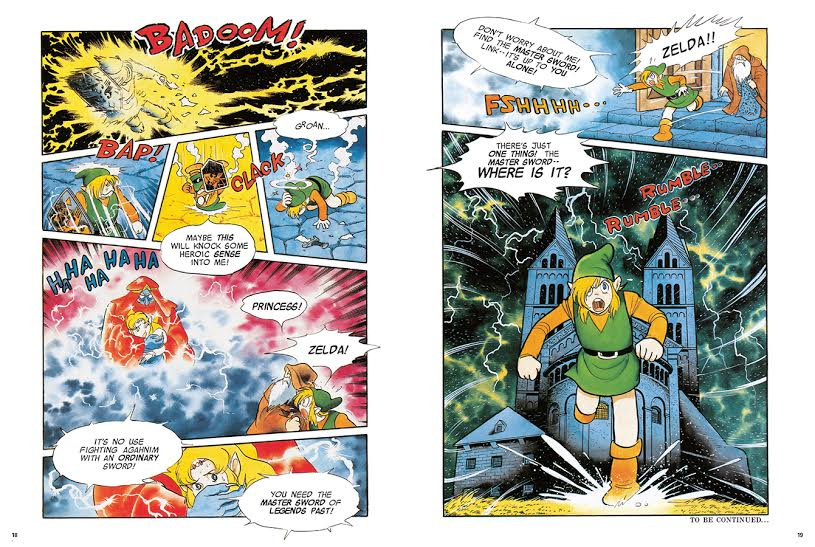

The story fascinated me. A boy named Link wakes in the middle of a stormy night, called forth by an urgent voice, and sprints toward the castle. In a matter of pages, his uncle dies at the hands of the evil wizard Agahnim, Link rescues and then loses the Princess Zelda (who communicates with him telepathically), and he learns that he’s the legendary hero who appears in Hyrule once every 100 years.

This, from a farm boy who falls over a lot and makes stupid faces.

I guess until this point, I had thought of Link as a Serious Hero. Someone who undertook a quest to save the world at no thought to what it might cost him. And Ishinomori’s Link does, but unlike the Link of video games, his version plunges into danger with a sense of humor—and a voice.

Link has never talked.

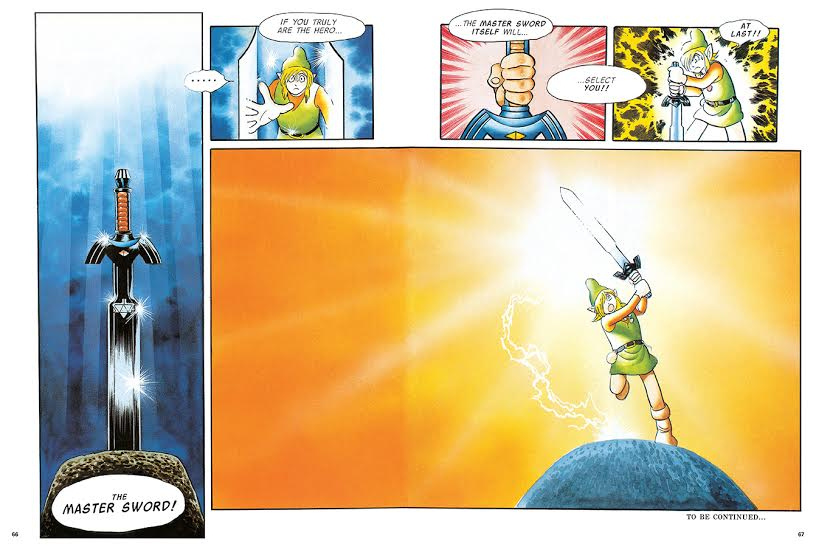

Giving a silent video game protagonist a voice is to change him from a blank slate to a character with thoughts and emotions of his own, and if I had to read about Link rather than play as him, that’s what I wanted him to be. I immersed myself in the idea of Hyrule. I read the Zelda II game manual cover to cover. I made my mom buy me a picture book called Moblin’s Magic Spear so I could see more of Link’s story. I wanted a part in his adventures. He wasn’t just Hyrule’s hero; he was mine.

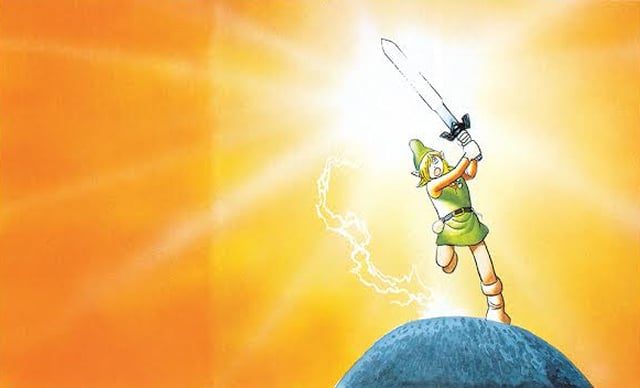

Ishinomori wasted no time in pushing Link out the front door and on through Hyrule in search of the Master Sword, and I love that even today. In the second chapter, Link travels from a “dark forest” to a “dangerous cliff” to a “slimy swamp” in the span of three panels (one page), and only shortly after rolling out of bed. Sure, he complains a lot about climbing stairs (and more stairs), but that only makes him awesome when he collects the Pendant of Courage and starts mowing down Agahnim’s goons like he’s the baddest fool in Hyrule.

Then back to goofy ol’ Link, charging headfirst into burning buildings and collapsing in a heap of exhaustion. Then switch to Link battling a centipede (a Lanmola) in the desert ruins and a giant spider in the Tower of Hera, and you can hardly believe they’re the same person. Link does the hero thing as naturally as washing the dishes.

Partway through, the story goes a little Dark Side of the Force with Link’s growing werewolf-ish beast arms and seeing his dead uncle and (dead? missing?) parents, who disappeared into the dark world. He ventures there, a place where the state of the mind shapes the body, turning men to monsters with their negative desires, and he seeks to destroy Ganon and recover the Triforce. The adventure never, ever slows down. Not for a second. One moment Link’s blowing up a whole fortress of baddies, and the next he’s climbing a tower that overlooks the world or battling fire and ice serpents on a lava lake.

I knew the serpents from Zelda II. I recognized Death Mountain in the story from that game, as well. And though Kakariko Village didn’t come till later, it could have been Ruto, or Rauru, or Nabooru to me. But the towns in Zelda II were paper cut-outs compared to how Ishinomori made them appear—a hub of activity, with humble citizens rebelling and helping Link in secret because they wanted rid of an evil king.

The ending goes a little The Wizard of Oz, and then Hyrule is saved. Link and Zelda (together) “totally destroyed” Ganon, according to the book (the “essence of the Triforce” is hardly an unreliable narrator). I had witnessed the story. The world was safe. What sense of wonder could that possibly leave me with?

A powerful one. Zelda and Link part, their story concluded, in a way more thoughtful and affecting than you’d ever see in the games.

Now, when I play them, I play ever in search for a story as full of adventure and surprise as this one, and for a world as mysterious and alive. I imagine myself in Link’s boots, and go trekking over mountains, deserts, and through swamps. I’m a kid again.

Stephanie Carmichael writes about video games, comics, and books when she’s not helping teachers and students have fun together with Classcraft, an educational RPG. Find her on her blog or on Twitter.

(Photo credits: The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past, TM & © 2015 Nintendo, THE LEGEND OF ZELDA: A LINK TO THE PAST © 1993 ISHIMORI PRO/SHOGAKUKAN)

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Published: May 28, 2015 10:00 am