When The Rise of Skywalker appeared in cinemas in 2019, many critics condemned it for playing to fanboy stereotypes that center male authority. Some deplored the decision to undermine Rey’s power by turning “Rey from nowhere” into the granddaughter of the evil Sith ruler Emperor Palpatine. Others drew attention to the lack of development for Rose and called out the filmmakers’ racist sidelining of Asian-American actress Kelly Marie Tran in the process.

If Rian Johnson’s The Last Jedi (2017) enabled women to take tentative steps forward, J.J. Abrams’ The Rise of Skywalker, it seems, was a huge leap backward for womankind.

On the other hand, female characters in The Rise of Skywalker have proportionally more screen time than in any other Star Wars feature film. Speaking purely about meaningful screen time, in which a character speaks dialogue or performs another significant action, with 51% of its runtime focused on named female characters with speaking parts, Skywalker is the first movie in the franchise to cross the 50/50 threshold for gender parity. The “Episode IX is for boys” narrative—a dangerous argument to make when many fans are working hard to establish that the franchise has always been for girls, too—is more complicated than it first appears.

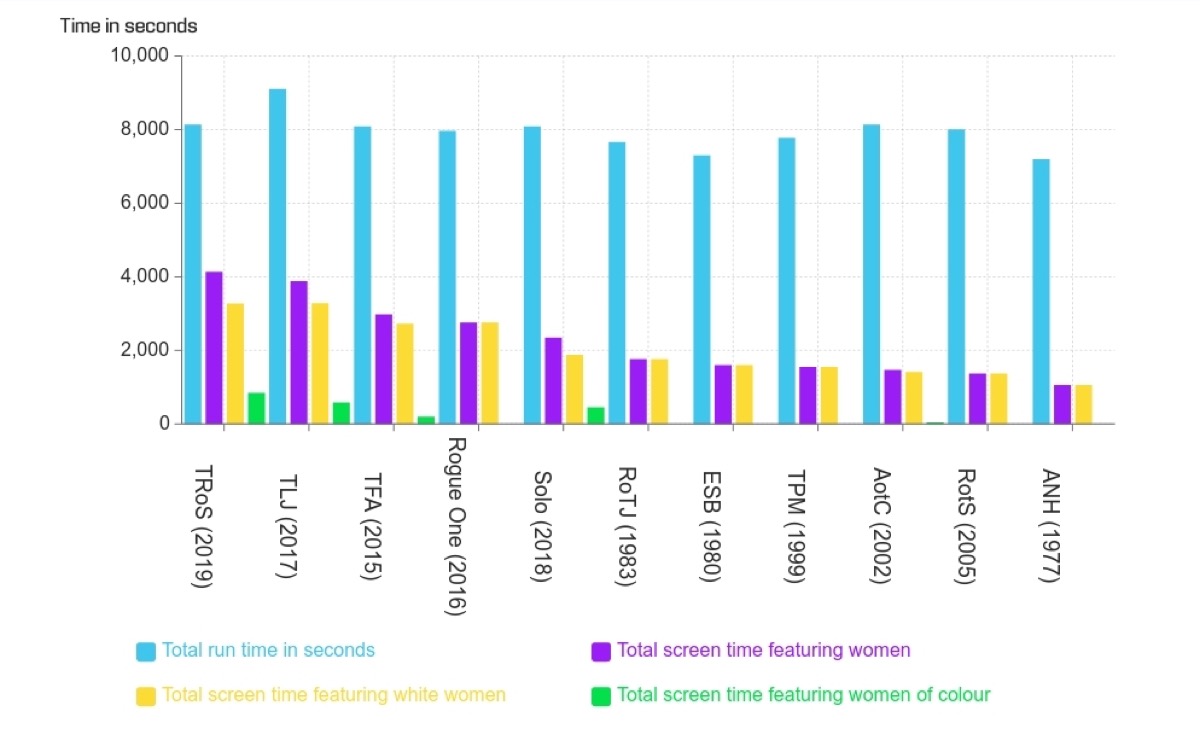

Statistically speaking, Skywalker is not only the best Star Wars feature in terms of women’s overall screen presence, but also at the intersection of gender and race, with white women securing approximately 43% and women of color 7.2% of the film’s run time. The result for women of color is, of course, appalling; 7.2% is not a figure we should be celebrating. It is only a marginal improvement on the next-best film in the franchise for gender equality, with female characters’ overall screen time in The Last Jedi totaling 43% and women of color accounting for 6.6% of the movie.

The gains in representation since the original trilogy and prequels are enormous, though, with The Rise of Skywalker eclipsing films such as 1977’s A New Hope (15% overall, with no women of color) and 2002’s Attack of the Clones (18% and 0.7% respectively).

Here’s a handy chart for every film in the franchise:

Of course, the burden of Skywalker’s female representation rests on the young shoulders of Rey (Daisy Ridley). While her contentious Palpatine heritage is a source of frustration among many fans (I argue that it makes us think about the class privilege of white women), there are many positive aspects to her depiction. In fact, the audience is often positioned as Rey throughout the film, via a series of closeups, extreme closeups, and point-of-view shots.

Thanks to the camera’s focus on Ridley’s face, we experience Rey’s emotions as she feels them and access her psychological space through the Force visions inside her head. When she gazes up at the crackling fire of Sith energy engulfing the Resistance pilots on Exogol, we see through her eyes; when she hears the voices of the dead Jedi that she alone can hear, we also hear them, too. We are at one with the Force, and the Force is with Rey.

There are other encouraging elements in the film, as well. Two women appear in the film’s opening crawl for the first time in the saga, with Leia and Rey both named. The movie passes the Bechdel-Wallace Test, and female characters inhabit a range of roles spanning the First Order (with female officers and, for the first time, female stormtroopers) and Resistance.

There is action-heroine Rey, courageous freedom-fighter Jannah (Naomi Ackie), kind yet aloof Spice Runner Zorii (Kerri Russell), and the loyal and smart engineer, Rose—who, despite her lack of screen time, does get the wittiest line in the film. When Poe (Oscar Isaac) announces that Palpatine has returned—”somehow”—Rose pointedly asks on behalf of the audience, “Are we meant to believe this?”

And while Leia’s inclusion is limited by the untimely death of Carrie Fisher in 2016, her death defies the violent ending that usually awaits Star Wars women. Unlike Shmi, Padmé, Lyra, Jyn, and Beru before her, she dies in comparative peace, surrounded by other women.

Nevertheless, despite these positive factors, much of the criticism leveled at Skywalker is justified, and no amount of number crunching is going to change that. The film is racist in denying Rose a story arc as it centers Rey. Its handling of Rey and Kylo’s relationship, while ambiguous and open to a variety of interpretations, is triggering for some survivors of gender-based violence, and the film squanders numerous opportunities to meaningfully explore female characters’ lives and feelings.

Jannah’s insurrection against the First Order is dealt with in just one line of dialogue; Zorii exists in relation to Poe rather than as a character in her own right. Connix, Captain D’Acy, Maz, and others are all left hanging at the Resistance base on Ajan Kloss, and their dialogue is limited.

It’s as if the (mostly male) filmmakers thought that women’s representation was just a numbers game: more women, more Rey, a higher ratio of female to male screen time, and the problem is solved. As most women know, it’s not that simple, and we should be careful not to let the numbers pull a Jedi mind-trick and convince us that the fight for equality in the Star Wars films is won.

Skywalker may have a higher percentage of screen time for women of color than The Last Jedi, but whereas Rose gets approx. 6% of Jedi to herself, she shares that 7.2% with Maz and Jannah in Skywalker. More women of color are condensed into proportionally less of the film on an individual basis. Until Lucasfilm President Kathleen Kennedy hires a woman of color to direct a feature film—and more women to tell more stories from female characters’ perspectives—the Star Wars woman problem will continue to haunt us like a troublesome Force ghost.

However, there are some reasons to be hopeful. Deborah Chow and Bryce Dallas Howard have directed episodes of Disney+’s The Mandalorian, and Chow is set to helm the forthcoming Obi-Wan Kenobi series. Leslye Headland’s appointment as writer and showrunner of a “female-centric” series might also inspire cautious optimism. And, while increasing diversity in Star Wars is likely down to the economic benefits that come with speaking to a wider proportion of the fanbase, there have been fairly steady improvements in screen time for female characters since the Disney takeover in 2015.

So, for now, we should stay critical of gender and especially race representation (particularly for women of color) in the franchise and continue holding filmmakers to account. But we can also celebrate Star Wars Day with the news that gender balance has finally—in terms of sheer numbers, at least—been brought to the Force.

(featured image: Disney/Lucasfilm)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Published: May 4, 2020 10:39 am