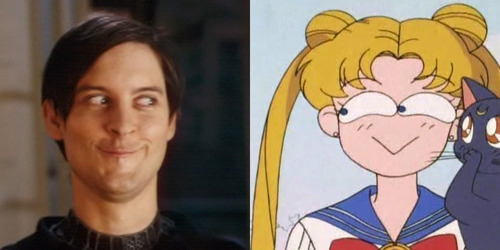

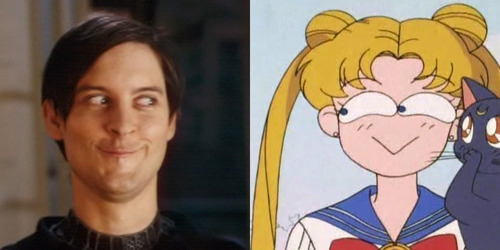

Did You Know Spider-Man And Sailor Moon Have A Shared Enemy?

Part 1

This is part one of a new three-part series from Theodore Jefferson, whose new book, The Incredible Untold Story of Sailor Moon, is available now.

Marvel declared bankruptcy in 1996, and one of the key reasons was its inability to get into the film business. Despite record-setting comic book releases only a few years earlier, Marvel didn’t have access to the box office dollars (and the attendant publicity) an iconic character like Spider-Man could bring them.

As it turned out, it took a marathon bankruptcy war to shake the necessary rights loose so Marvel could make their movies. Film fans and comic book fans alike have enjoyed the fruits of Marvel’s Cinematic Universe ever since, culminating in the billion-dollar Avengers film in 2012.

The reason Marvel had so much trouble in the 1990s is because up to ten companies owned a share of the rights to make a Spider-Man film. It would have required a unanimous consensus to get anything into production, and anyone who works in this town will tell you a unanimous anything in Hollywood is virtually impossible.

One of the great strengths of the Sailor Moon license during the same period was that DIC CEO Andy Heyward made certain to acquire a full portfolio of rights to Sailor Moon in a large enough territory to make those rights worthwhile. As the English-language licensee, DIC had manufacturing, recording, syndication, adaptation, home video, interactive, apparel, and some limited publishing rights, along with a rumored inside track on some share of the film rights.

As a result, DIC was able to manufacture toys, games, apparel, some books, VHS home video, DVDs, audio CDs, and even a video game. Sailor Moon wasn’t near the financial success in the United States and other English-speaking territories that it was in Japan, but because of its ambitious licensed merchandising, it certainly wasn’t a disaster either.

Unfortunately, the Sailor Moon of 2015 is far different than the Sailor Moon of 1995. The licensing situation for the character in English-speaking territories in 2015 is an unfathomable train wreck. One need only look for the dedicated Sailor Moon section that isn’t on Amazon or the “coming soon” pages on Viz Media’s official site for confirmation of this state of affairs. This is a property that is worth almost as much as the New England Patriots, and it has an “under construction” website almost eight months after its new episodes premiered!

Toei and Bandai have apparently never awarded any significant rights outside of Japan aside from home video and streaming. Viz Media claims to have interactive rights but appears to be unable to do anything with them, and to put a little frosting on this half-a-loaf approach, it appears Toei Animation might be competing with their own licensee by making side-deals for streaming Sailor Moon in English.

The similarities between the Spider-Man of the 1970s and 1980s and the Sailor Moon of 2015 are both remarkable and inexplicable. Here is a property with ten-figure potential (Sailor Moon) that literally can’t get out of its own way.

One wonders why it was ever licensed in the first place. Aside from whatever is being purchased in and shipped from Japan, Sailor Moon has no apparent source of significant income! There’s no business case for this show outside of Japan.

This situation is devastating for the property itself and more importantly, highly discouraging for fans. The Marvel of the 1990s was personified by a distant, uninterested billionaire, and so is the “Sailor Moon Inc.” of 2015. English-language fans, particularly in Canada, feel left out and abandoned. The situation is tarnishing the property and the characters, and it is forcing numerous companies other than Toei and Bandai to leave money on the table.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

If asked, any animation executive will tell you a show by itself is worthless aside from its utility as a commercial for all the other stuff you want to sell. This has been true of both animated television and film dating back to the 1970s and 1950s respectively. Disney built an empire on animated film rights starting with Winnie the Pooh, and companies like Hanna Barbera, Hasbro, and Mattel did the same with animated television during the breakfast cereal wars of Jimmy Carter’s presidential term.

On television, animation was cheap and plentiful. Fred Flintstone could run the 800m hurdles in his living room while passing the same chair sixteen times, the Transformers transformed at about four frames a second, and roughly half of Scooby Doo was the same run cycle for each character moving between opening and closing doors during groovy music montages.

The kids didn’t care. Mattel sold enough Hot Wheels track to circle the Earth, Barbie took over half of every toy store in America, and even the world’s least geeky kid owned at least one Transformer. That potential is why Andy Heyward pursued the Sailor Moon rights in 1994. That potential is why Ronald Perelman took 46% of the stock in Toy Biz and gave future billionaire Ike Perlmutter a perpetual royalty-free license to make Spider-Man action figures at about the same time.

But in 2015, there is no company in America capable of doing the same thing for Sailor Moon. According to my sources, Viz Media simply lacks the right to do anything except market the show itself. Without some kind of syndication deal that third parties can monetize, those rights have no value. They are particularly limited when the show’s licensor is also marketing the show.

Then there’s the issue of three versions of the same show: three companies with three different visions and three different directions. DIC marketed Sailor Moon to children. Viz is marketing Sailor Moon to nostalgic young adults. Toei is marketing Sailor Moon to manga readers.

Meanwhile, all of the merchandising is five thousand miles away. The licenses are five thousand miles away. There is nobody here in this market championing the property. There is no company with the right to do what is necessary to turn the good will Sailor Moon has accumulated over the years into a vision for her future.

And the fans are growing more and more unhappy about it.

The situation is almost exactly the same as the one facing Spider-Man during the Marvel bankruptcy. Fans were discouraged by talk of breaking up Marvel and selling the pieces off, and the reason a company with more than 3500 characters was completely unable to do anything worthwhile is because Spider-Man was quite literally tangled in his own web.

When I worked for DIC, my job was to help find ways to maximize the value of the English-language Sailor Moon character license.

In Part Two of this three-part series, I’ll show you what Bandai and Toei could have done differently three years ago, and twelve years ago, and how it would have delighted Sailor Moon fans around the world.

Theodore Jefferson is the author of The Incredible Untold Story of Sailor Moon, the definitive history of the world-famous animated television series in the United States and other English-speaking territories. Mr. Jefferson is a founding member of the Lexicon Hollow Authors Guild and also writes for Moon Game.

Are you following The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]