Schadenfreude Found To Be Biological In Nature, Linked To Feelings Of Envy

So all those haters really are just jealous.

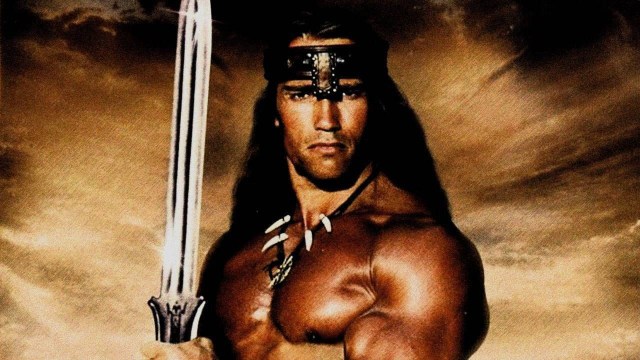

What is best in life? According to both Conan the Barbarian and researchers at Princeton University, it’s crushing your enemies, seeing them driven before you, and hearing the lamentation of their women. Or, well, knowing that they have been crushed, at least.

In order to explore why people experience a lack of empathy with others based on perceived identities, graduate student Mina Cikara and Princeton professor Susan Fiske set up a series of four experiments that tested the amount of pleasure subjects felt when being told stories about others’ misfortune. According to the paper they published in Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences this year, their subjects were shown images of people who stereotypically tend to illicit certain emotions — for example, the elderly (pity), drug addicts (disgust), everyday Americans (pride), and rich yuppie types (envy) — and paired them up with either positive, negative, or neutral events. Since most people would not actually admit to getting a kick out of hearing when people, the researchers measured the electrical activity of cheek muscles to figure out whether or not their subjects were suppressing smiles. In another experiment, they used self-reporting and functional magnetic resonance imaging to

What they found was pretty unsurprising — a large majority of those tested seemed to feel the best when hearing stories about bad things happening to the rich professional, and felt the worst when hearing about good things happening to that same person. In a follow-up survey as part of the second experiment, many people even freely admitted that they would have no problem inflicting some kind of pain on the professional in a hypothetical Milgram experiment scenario.

However, when the researchers added mitigating factors to the professional’s story in the third experiment — for example, depicting a banker who works pro-bono (illiciting pride) or who has lost their job but still dresses up for work every day (pity) — the initial feelings of envy lifted pretty easily and some felt less joy at the imagined person’s suffering.

The final experiment focused specifically on how fandom and rivalry affects this behavior; subjects were prescreened as either Boston Red Sox or New York Yankee fans and were made to watch a series of plays between both teams. Overall, most of the people in this experiment tended to feel better when their own team performed well, but also had very positive reactions when their rival team lost against a neutral team (the Baltimore Orioles, in this scenario).

Cikara and Fisk hope that by studying these biological reactions, they can explore the ways in which group think and stereotype-based rivalries can impact not just sports fans, but everyday situations and even global diplomacy.

“As far as other people are concerned, [America is] the world’s bullies, and we have data that show that,” Fiske said in a statement. “And so, if we want to work with another country, it’s not the respect we’re lacking; it’s the trust. We need to remember that these stereotypes really affect how we enter other settings.”

“A lack of empathy is not always pathological. It’s a human response, and not everyone experiences this, but a significant portion does,” Cikara added. “[…] It’s possible, in some circumstances, that competition is good. In other ways, people might be preoccupied with bringing other people down, and that’s not what an organization wants.”

(via Phys.org, image via Conan the Barbarian)

- Speaking of schadenfreude, want to watch a bunch of people fall down?

- Or maybe you’d like to see this dumb guy lose a slap fight to an actual Conan the Barbarian

- We won’t deny that we felt pretty great when we heard about all those Zynga layoffs

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]