Scientists Use Hubble to Make First Ever Direct Observation of Disc Around Black Hole

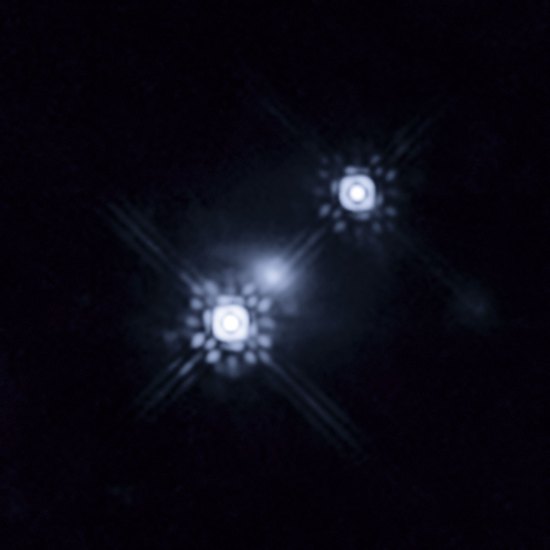

As is common knowledge, black holes cannot be seen since their intense gravity prevents even light from escaping. However, such cataclysmic objects can not go entirely unnoticed. Using the Hubble Space Telescope, scientists have observed the disc of spinning dust and gas surrounding a black hole called a quasar accretion disc through a process called gravitational lensing. This is the first time astronomers have been able to observe and measure the properties of a quasar directly. In the image above, the quasar is the smeary spot above the bright galaxy in the foreground.

As amazing as this accomplishment is, the process scientists used to make it are equally staggering.

For scientists, these observations are particularly interesting because quasars and black holes have mostly been discussed in theoretical terms. While we have learned much about these objects over the years, confirming our beliefs is extremely difficult. The lead author on the new study on quasars, Jose Muñoz, is quoted by PhysOrg as saying:

“This result is very relevant because it implies we are now able to obtain observational data on the structure of these systems, rather than relying on theory alone,” says Muñoz. “Quasars’ physical properties are not yet well understood. This new ability to obtain observational measurements is therefore opening a new window to help understand the nature of these objects.”

The trouble with quasars, which stands for quasi-stellar radio source, is that they are relatively small compared to the distances between us and them. The distance across a quasar’s disc is some 100 billion kilometers, but most are billions of light years away. According to PhysOrg, being able to look directly at one is akin to looking at individual grains of sand on the moon.

To see the quasars, the research team took advantage of the stars in a galaxy that just happened to lie between the Hubble and the quasars they wished to observe. Instead of obscuring their view, the incredibly gravity exerted by the stars actually amplified some of the light from the quasar. It’s called gravitational lensing, and in this case scientists were able to use it like a scanning electron microscope on a galactic scale.

Using a series of such images, scientists were able to estimate the size and determine the color of the quasars in question. Far from simple asthetics, the color of the quasar gives scientists some idea of the temperature of the disc. As the dust and matter wind closer to their eventual doom in the heart of a black hole, they get hotter and glow bluer. From their observations, scientists estimate the quasar disc to be between 100 and 300 billion kiometers across, or about 11 light-days. That’s a pretty big margin, but impressive when considering the process involved.

With this technique in place, whole new avenues of observation could be opened up to scientists. Using gravitational lensing, its possible to see further and gain more information than ever before. Though humans may never see these incredible sights with their own eyes, scientists can now peer deeper into the heart of the universe.

(PhysOrg via Hacker News, Universe Today)

- 600 gamma ray sources are still puzzling scientists

- But we have a good idea of what created Hanny’s Voorwerp (Spoilers: black holes)

- Peering into other dimensions, with black holes

- Denny’s is pretty much the black hole of the soul

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]