According to This Psychologist, Sherlock Holmes Isn’t a Sociopath at All

and let it be known

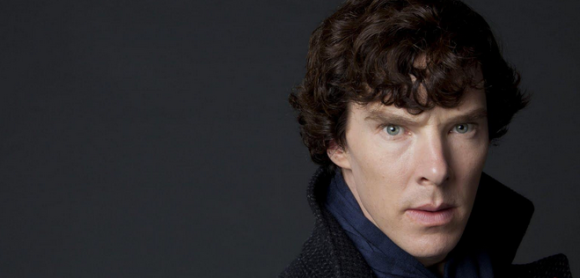

Psychologist Maria Konnikova is peeved with some of the discussion going on around Sherlock. Why? Is it the mystery of the exact events of the season three two finale? Is it the pre-emptive hatred some sectors of the fandom seem to have developed for CBS’s Elementary? Hell, is she just wondering who Benedict Cumberbatch is playing in Star Trek 2?

No, it’s something that makes far more sense given her profession: Konnikova would like us all to stop referring to Holmes as a sociopath. Because according to her very compelling argument, he’s not.

There is a scene, in the pilot (“A Study in Pink”) of BBC’s Sherlock, in which police minion and continuous thorn-in-Holme’s-side Anderson calls Sherlock a psychopath. Our lead whips around, all spitting retort: “I’m not a psychopath, Anderson, I’m a high-functioning sociopath, do your research!”

The moment is memorable, among Sherlock’s many (oh, many) comebacks, for highlighting what seems to be a key aspect of the introduction of the character. But according to Konnikova, there are a number of falsehoods being perpetrated by the exchange (full text can be found here):

Sherlock Holmes is not a sociopath. He is not even a “high-functioning sociopath,” as the otherwise truly excellent BBC Sherlock has styled him (I take the words straight from Benedict Cumberbatch’s mouth). There. I’ve said it.

First of all, psychopaths and sociopaths are the exact same thing. There is no difference. Whatsoever. Psychopathy is the term used in modern clinical literature, while sociopathy is a term that was coined by G. E. Partridge in 1930 to emphasize the disorder’s social transgressions and that has since fallen out of use. That the two have become so mixed up in popular usage is a shame, and that Sherlock perpetuates the confusion all the more so. And second of all, no actual psychopath-or sociopath, if you (or Holmes) will-would ever admit to his psychopathy.

Konnikova goes on to describe what goes into the diagnosis of sociopaths, a lot of the things on the list do seem like they apply to our famous detective.

According to Konnikova, however, there are key differences. Speaking to his coldness in particular:

Holmes’s coldness is nothing of the sort [that is found in true psychopaths]. It’s not that he doesn’t experience any emotion. It’s that he has trained himself to not let emotions cloud his judgment-something that he repeats often to Watson. In “The Sign of Four,” recall Holmes’s reaction to Mary Morstan: “I think she is one of the most charming young ladies I ever met.” He does find her charming, then. But that’s not all he says. “But love is an emotional thing, and whatever is emotional is opposed to that true cold reason which I place above all things,” Holmes continues. Were Sherlock a psychopath, none of those statements would make any sense whatsoever. Not only would he fail to recognize both Mary’s charm and its potential emotional effect, but he wouldn’t be able to draw the distinction he does between cold reason and hot emotion. Holmes’s coldness is learned. It is deliberate. It is a constant self-correction (he notes Mary is charming, then dismisses it; he’s not actually unaffected in the initial moment, only once he acknowledges it does he cast aside his feeling).

What’s more, Holmes’s coldness lacks the related elements of no empathy, no remorse, and failure to take responsibility. For empathy, we need look no further than his reaction to Watson’s wound in “The Three Garridebs,” (“You’re not hurt, Watson? For God’s sake, say that you are not hurt!”)-or his desire to let certain criminals walk free, if they are largely guiltless in his own judgment. For remorse, consider his guilt at dragging Watson into trouble when the situation is too much (and his apology for startling him into a faint in “The Empty House.” Witness: “I owe you a thousand apologies. I had no idea that you would be so affected.” A sociopath does not apologize). For responsibility, think of the multiple times Holmes admits of error whenever one is made, as, for instance, in the “Disappearance of Lady Frances Carfax,” when he tells Watson, “Should you care to add the case to your annals, my dear Watson, it can only be as an example of that temporary eclipse to which even the best-balanced mind may be exposed.”

And as always, something in a Sherlock-related article makes us go awwww:

But the most compelling evidence is simply this. Sherlock Holmes is not a cold, calculating, self-gratifying machine. He cares for Watson. He cares for Mrs. Hudson. He most certainly has a conscience (and as Hare says, if nothing else, the “hallmark [of a sociopath] is a stunning lack of conscience”). In other words, Holmes has emotions-and attachments-like the rest of us. What he’s better at is controlling them-and only letting them show under very specific circumstances.

So there you have it: The opinion of a professional. You can read her entire essay over at io9, and we highly encourage you to do so.

In a lot of ways, it makes sense that the show’s writers would want to view their Sherlock as a sociopath; it’s one in a long line of shows or films that attempt to harness the complicated mental lives of the psychopathic of the world, often to break away from the clinical definition when stretching the character and the story to fit into what many may find to be a more satisfying emotional arc for the viewer.

So, what do you think? Do you agree with Konnikova’s analysis of the character? Do we have any educated members of the commentariat who’d like to speak up on the matter?

(via io9) (Image via Spoiler TV)

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]