Stop Marketing Black Sci-Fi as the “Black Version” of White Stories

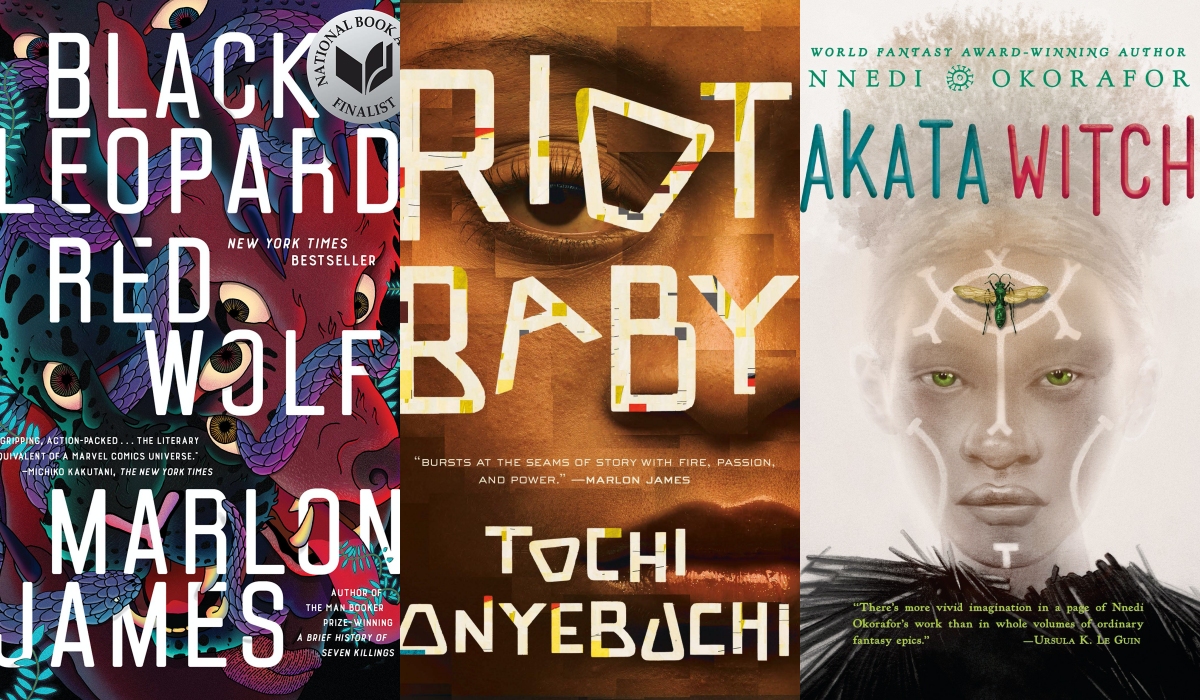

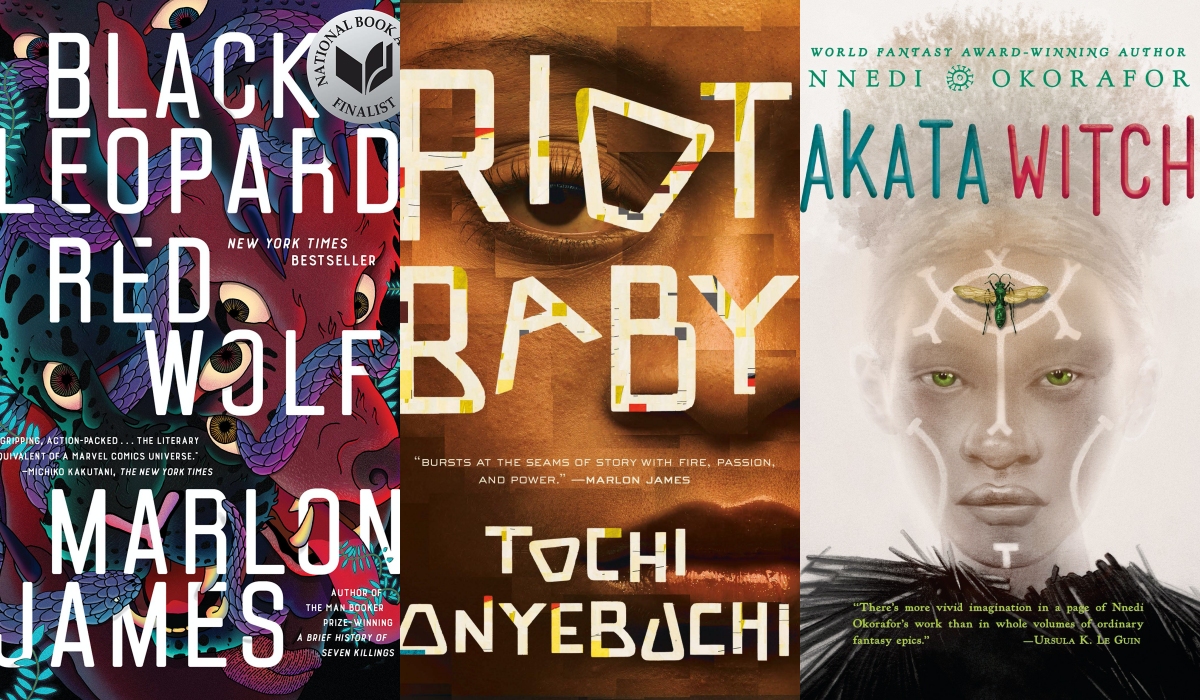

(Tor.com, Riverhead Books, Speak)

Nigerian-American writer Nnedi Okorafor shared a tweet a while back where she asked people to stop referring her young adult series Akata Witch as “Nigerian Harry Potter.” This is something she’s been saying for a long time.

I try to get people to stop calling the Akata series a “Nigerian Harry Potter”, but ppl keep doing it.🤷🏾♀️

My stories aren’t the black version of white authors. My foundation isn’t whiteness (no disrespect to whiteness). Ijs.

My foundation geminated in Arondizuogu & Isiekenesi.

— Nnedi Okorafor, PhD (@Nnedi) October 16, 2018

For a lot of people, it might be confusing as to why it would be rude or dismissive to compare a book about a magical school to one of the most popular series of children’s books of all time, but the reality is that by distilling Black science-fiction and fantasy into the Black or African expy of something else, you are often erasing the actual inspiration of the works: our Blackness.

The inspiration for this thinking was when I was reading Riot Baby by author Tochi Onyebuchi. Riot Baby is about a young woman named Ella, who has these powerful psychic abilities, and her brother, Kev, growing up in the aftermath of the Rodney King riots and dealing with the agony of racism. Ella, who has these godlike powers, is torn between the knowledge that these powers could make a difference for her and her brother, but also the fear of herself she was raised with.

I could see the inspiration from different superhero and anime properties, especially Akira, but when you get to the acknowledgment, the person he thanks at the end is fellow author N.K. Jemisin. He thanks her for her series and says,

Until I read her Broken Earth trilogy, I did not know how to write angry, the type of angry that still leaves room for love. Those books unlocked a gate. The reader in me is ever grateful. So is the writer.

The biggest inspiration for most Black writers are other Black creatives, especially those who were unafraid to infuse their Blackness into their narratives.

This isn’t to say that we are not inspired or influenced by non-Black art. The works of Jane Austen, plus all the magical girl anime and shonen I’ve watched, are very much a part of my creative blueprint. However, the confidence to tell Black stories often comes from seeing others do it first.

The first time I read Kindred by Octavia E. Butler, I felt the possibility of creating stories that were fantasy, but with Black American History. Reading the works of N.K. Jemisin showed me that building sci-fi worlds outside of the white fantasy gaze was not just possible, but that the range of possibilities would be incredible.

I loved Riot Baby because it felt so unapologetic in its rage and frustration. In an interview with Marlon James at Strand, Onyebuchi broke down how the term “dystopian” is usually framed around white people and white experiences, because the dystopia is already happening to Black people:

And there’s a part towards the end of the book that gets into the near-future, but the vast majority of it is set in the here and now, in the recent past, but they’ll still use that term “dystopian.” And it got me thinking, dystopian for whom? Because this is just stuff that I’ve seen. This is stuff that I know people have experienced and that I’ve witnessed and that I’ve heard, that I’ve watched people suffer through. What happened after Rodney King, is that dystopian? You know, dystopian for whom? And so that I think is a very interesting new dimension to what I’m having to consider with regards to the fiction that I’m writing that wasn’t necessarily like—you know, War Girls is set like hundreds of years into the future, so you could see it with that: “dystopian.” It doesn’t really work with Beasts or Crown, but it’s interesting seeing dystopian applied to aspects of the African-American experience.

By always comparing Black science-fiction to its white “counterpart,” it shifts the center away from how the text was attempting to prioritize Blackness and Black mythology, history, pain. Marlon James called his book Black Leopard, Red Wolf “the African Game of Thrones” as a joke, but it became a tagline that wouldn’t go away:

You know, the danger of the African Game of Thrones line would be to say, “You think Europe was great, Africa was even better.” And it doesn’t do that. It takes it for granted that these were great empires, that these were places of great myth and magic, in a way that I loved. It doesn’t do any special pleading. These empires were powerful, great, interesting, small, petty, all that. As a reader, it was such a relief.

It is fundamentally important that we give authors like Samuel Delany, Octavia E. Butler, and L.A. Banks credit for being the blueprint for a lot of this new generation of Black authorship. They are our ancestors as much as Tolkien and Le Guin. That African mythology and empire is just as rich for cultivation, narratively, as European mythology.

We need to acknowledge that Black fiction can thrive in connection to each other, without needing to prop it up on the shoulders of whiteness, unless that comparison is built into the text.

Here are some recent, great Black Sci-fi recommendations not mentioned above (but seriously Riot Baby is amazing, check it out). Add any of your favorites down below:

Ring Shout by P. Djèlí Clark, Dread Nation by Justina Ireland, The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms by N.K. Jemisin, A Taste of Honey by Kai Ashante Wilson, and Shadowshaper by Daniel José Older.

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]