Our Books, Our Shelves: Stop Explaining Everything

Many years ago, when I was young and convinced of my own superiority, I applied for one of those premise-of-a-TV-show kinds of jobs where the basic requirement is to check your morals at the door and commit to the ruthless manipulation of other people for fun and profit. (Sadly, this really could be any number of jobs.)

However, to successfully manipulate people you need some interpersonal skills. This posed a problem since I, as a lifelong Awkward Person, have none. So when they asked me why I was qualified for a career as a borderline sociopath, I said, “I write stories. My entire hobby is thinking about psychological cause and effect. Writers build people, and we give them specific histories of hurt that produce their particular motivations and desires, and we use that to explain why they do what they do. Stories are clockwork universes that run on the logic of the psyche.” I refrained from adding, sociopathically, And the author is God.

I got the job. I was, predictably, deeply shitty at it because of the aforementioned lack of interpersonal skills. I was also starting to realise that I was writing shitty stories that suffered from what I like to call psychological determinism.

All stories are carefully crafted narratives, tidier and more graspably meaningful than any set of real-life events. That’s what stories are. And it can be distinctly satisfying, in the way of solving an equation or seeing a puzzle come together, to be led through a story where each beat of character action and reaction rests understandably on some previously placed element. Something we’ve come to know about a character’s past, perhaps, or a character moment that revealed some fundamental aspect of their personality. The story repeatedly raises the question, why does this person do this? and then gives the answer along with all the information needed to make sense of it: because.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with the equation approach to storytelling. We like things to make sense. But it becomes a problem when that desire for sense becomes the desire to answer every question of why did they do this? so thoroughly and rigorously that it might as well be a presentation to a thesis defence committee.

In pursuit of watertight story logic, writers can find themselves tracing that causal chain of psychological cause and effect—because, because, because—all the way back to a character’s origins. And since every chain of logic has to begin with an axiom, they create one: a single defining event that then becomes the fixed and unbreathing core of the character, because it’s the foundation of every thought, action and reaction they will ever have.

But what kinds of airless stories are we telling, when the characters are so fully-known, so readily explicable by one foundational moment, that they might as well be on rails? Is the Joker’s malice more compelling, or Hannibal’s cannibalism more seductively thrilling, if we know what traumatic event in their past made them that way? Do we feel more for Cruella de Vil if we know that everything she does is because Dalmatians killed her mother?

Stories like these are the clockwork universes of our design, constrained so tightly by their own logic—excavated so thoroughly by explanation—that the surprise, the emotion, the fearful confrontation with what is unknown and uncertain and inexplicable that is life, has been pressed out of them completely.

When I sat down to write a story of an uneducated 14th-century Chinese peasant girl who rises to become the founding emperor of the Ming dynasty, my first impulse was to explain. I wanted to find the root cause of why this one person, out of all the undistinguished peasants of China, was able to refuse the role she was born into and the value that the world assigned to her. Find why this person was capable of not just imagining a destiny radically outside her own experience of the world, but also of wanting it. Why was this person tenacious enough, ambitious enough, opportunistic enough, to become one of history’s greats?

But the more I explained, the smaller and flatter and more ordinary that character became. Every explanation squeezed more of the greatness out of her. Until, gradually, I realised that the only narrative choice that worked was to not explain. To refuse the cause. To say, simply: because that’s the way she is.

The great mythic figures of our storytelling all have a hole at their core. Why did Achilles choose a short blaze of glory over a long life? Why was Alexander the Great never satisfied no matter how broad his empire grew? It’s that hole—that fundamental mystery of why some people are extraordinary—that thrills and unsettles. It’s the feeling that births our monsters, but also our heroes.

When we encounter these characters on the page, we feel like we’re encountering emotion itself. We’re frightened and overwhelmed and consumed by the experience of meeting something powerful and inexplicable—something that is and will always be outside our control. The actions of these characters aren’t irrational, but they aren’t predictable. Our reading of the blank space at their core is constantly flickering as we struggle to fit each action and reaction into a framework of understanding. But there’s never any single right answer. There’s no axiom to deduce. We read into the character, rather than have them read to us as a single cause, a single long chain of effect.

And this feels unsafe. It feels unpleasant to be told: no certainty for you. But in giving it up, what do we get? The excitement of discovery, the shock of the new. Fear and frisson and life.

So let’s write stories with characters that sweep us away, that frighten us. Whose origins and innermost secrets remain, at least in part, stubbornly for themselves. We don’t have to know everything. Leave those spaces on the map blank, and say: here be dragons.

Get your copy of She Who Became the Sun here.

About the Book:

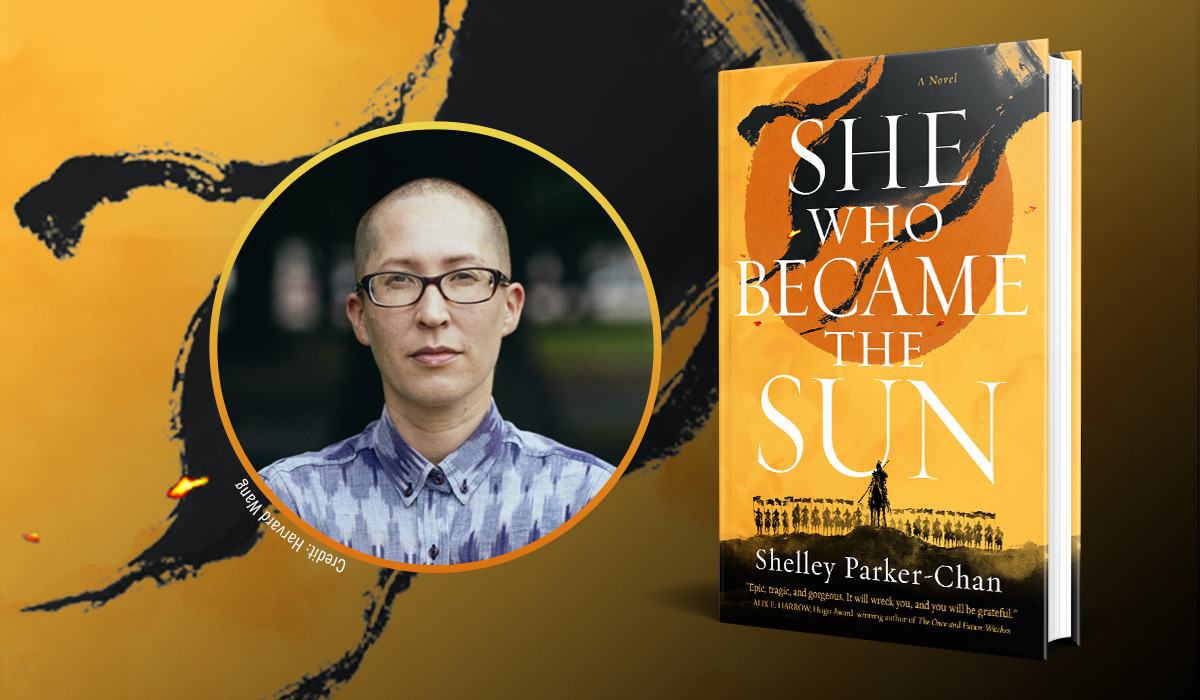

Mulan meets The Song of Achilles in Shelley Parker-Chan’s She Who Became the Sun, a bold, queer, and lyrical reimagining of the rise of the founding emperor of the Ming Dynasty from an amazing new voice in literary fantasy.

To possess the Mandate of Heaven, the female monk Zhu will do anything

“I refuse to be nothing…”

In a famine-stricken village on a dusty yellow plain, two children are given two fates. A boy, greatness. A girl, nothingness …

In 1345, China lies under harsh Mongol rule. For the starving peasants of the Central Plains, greatness is something found only in stories. When the Zhu family’s eighth-born son, Zhu Chongba, is given a fate of greatness, everyone is mystified as to how it will come to pass. The fate of nothingness received by the family’s clever and capable second daughter, on the other hand, is only as expected.

When a bandit attack orphans the two children, though, it is Zhu Chongba who succumbs to despair and dies. Desperate to escape her own fated death, the girl uses her brother’s identity to enter a monastery as a young male novice. There, propelled by her burning desire to survive, Zhu learns she is capable of doing whatever it takes, no matter how callous, to stay hidden from her fate.

After her sanctuary is destroyed for supporting the rebellion against Mongol rule, Zhu takes the chance to claim another future altogether: her brother’s abandoned greatness.

About the Author:

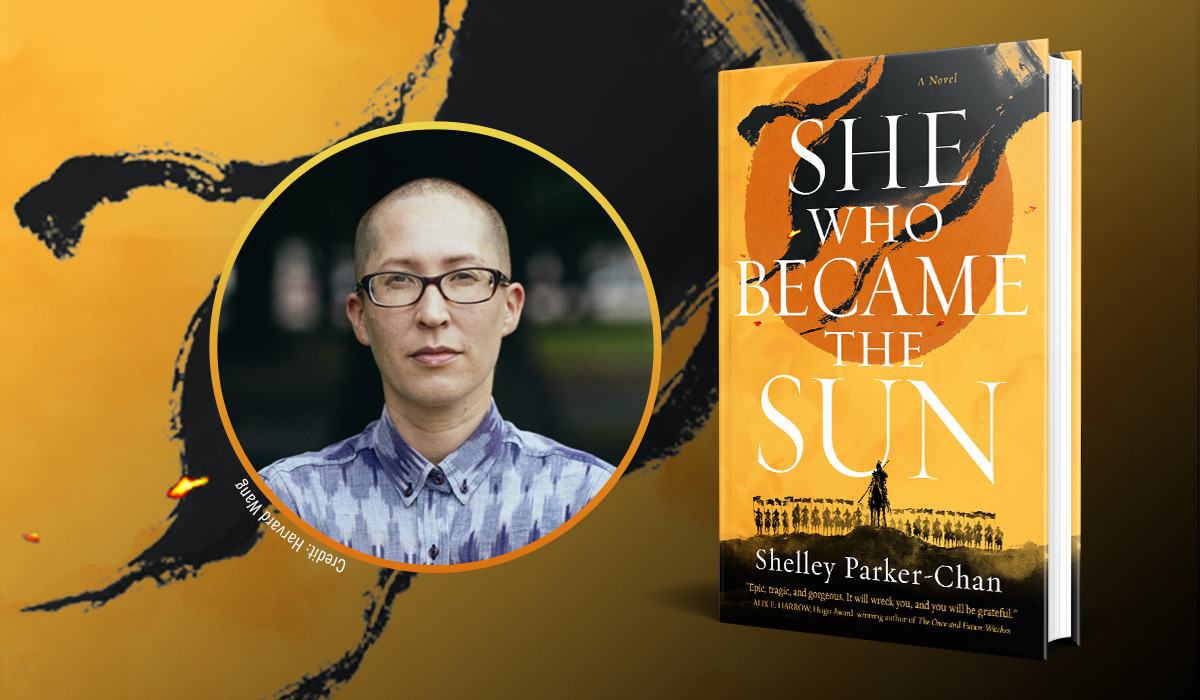

Shelley Parker-Chan is an Australian by way of Malaysia and New Zealand. A 2017 Tiptree Fellow, she is the author of the historical fantasy novel She Who Became the Sun. Parker-Chan spent nearly a decade working as a diplomat and international development adviser in Southeast Asia, where she became addicted to epic East Asian historical TV dramas. After a failed search to find English-language book versions of these stories, she decided to write her own. Parker-Chan currently lives in Melbourne, Australia, where she is very grateful to never have to travel by leaky boat ever again.

Don’t forget to check out the other excellent additions in our exclusive Our Books, Our Shelves column with Tor Books!

- A.K. Larkwood & Tamsyn Muir in Conversation, by A.K Larkwood and Tamsyn Muir

- BE A QUITTER, or HOW TO WRITE THE NOVEL OF YOUR HEART, by K.M. Szpara

- Down with Literary Snobbery, Long Live Genre, by Sarah Kozloff

- Bestselling Author John Scalzi Talks the End of Everything with John Scalzi

- A Billion Thoughts at Once by TJ Klune

- RIP, IRL: Fandom Has Always Lived Online by Camilla Bruce and Kit Rocha

- Alaya Dawn Johnson on Writing and Book Advocacy with Alaya Dawn Johnson

- On Persistence, Nearly Giving Up, and Writing On by Martha Wells

- The Piss Problem: The Politics Behind Peeing in Space by Mary Robinette Kowal

- What Can Gender Swapping in Stories Tell Us About Ourselves by Kate Elliot

- An Exclusive First Look Behind The Scenes of Bestselling Author V.E. Schwab’s New Novel, The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue with V.E. Schwab

- A Celebration Of Chaotic Good with Andrea Hairston, S.L. Huang, S.A. Hunt, and Ryan Van Loa

- The Fallacy Of The Universal by Mark Oshiro

- Bookish Activism & Rejecting Fatalism In Favor of Hope by Cory Doctorow

- Go To The Bookstore With V.E. Schwab, Bestselling Author of The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue by V.E. Schwab

- Christopher Paolini’s Love Letter To Sci-Fi by Christopher Paolini

- Come For The Worldbuilding, Stay for the Character Development: Brandon Sanderson’s Rhythm of War

- History is Quicksand, Stories Are What I’ve Got by Nghi Vo

- Art in the Year of Calamities by Jenn Lyons

- Sarah Gailey on Putting Yourself Into Your Characters by Sarah Gailey

- J.S. Dewes and Karen Osborne in Conversation

- An Exploration of Show and Tell by Marina Lostetter

- Crafting Your Own Reality by Nghi Vo

- Juneteenth and Freedom by Lucinda Roy

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]