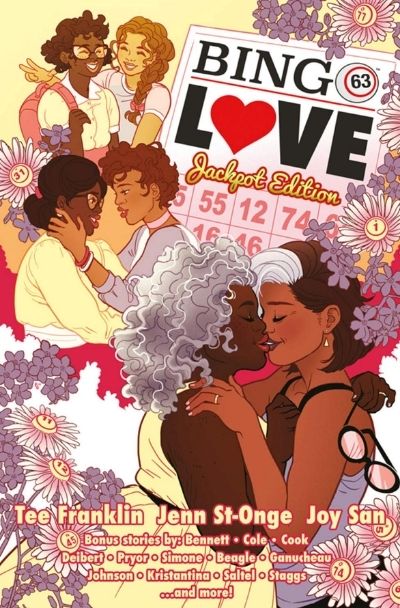

After months of anticipation, I finally got around to reading some of Tee Franklin’s work—specifically Bingo Love: Jackpot Edition and Harley Quinn: The Animated Series: The Eat. Bang! Kill. Tour. I’d been following her on Twitter for a minute, and her matter-of-fact approach to promoting her work is something I really admire as an artist. Upon learning that Franklin was the writer for a (then) upcoming Harley Quinn comic-run, and it would act as a canon—between seasons two and three—tie-in for HBO Max’s Harley Quinn: The Animated Series, I took the plunge at my local comic book store and signed up for my first ever pull box.

It’s already hard enough to wait week-to-week for episodes of a show, but to wait month-to-month for 20 pages of story per issue!? I know how it works, and I couldn’t handle it. So, instead, I dodged all spoilers and waited to read my pulls in February when ALL the issues were out. Also, because it was Valentine’s Day Season and Black History Month, I checked Bingo Love out of my library because when I typed Franklin’s name into the search bar, of course, another cute queer romance would show up.

If you’re looking for a glorious review of The Harley Quinn: The Animated Series: The Eat. Bang! Kill. Tour Issue One, please check out TMS fandom editor Briana Lawrence’s review! Then, read the entire run, because the story is a blast and so heartfelt, especially if you’ve been following Harley and Ivy’s friendship-turned-relationship on HBO Max. Instead of getting into the weeds of the story, I want to talk about how Franklin and her artists have disability representation embedded in both Harley Quinn and Bingo Love: Jackpot Edition.

*Light visual spoilers for each incoming and plot spoilers for Bingo Love.*

Disability representation in comics

Depending on who you cite,15–30% of people live with at least one disability at any given moment. Pre-COIVD-19 governments and global networks put the number at 15–20%. However, activists and those who study accessibility more broadly often cite the higher numbers to account for those without access to affordable healthcare, misdiagnoses, and non-visible disabilities. Why do I say this? Because with numbers like that, you’d think disability would be more visible and narratively woven into stories, but it’s usually not, unless we’re talking about a handful of heroes and a troublingly overwhelming list of villains. A number of tropes exist, within comics and media at large, where the villain is physically disabled.

Beyond one or two characters in a given work, I have rarely seen so much disability representation until reading Franklin’s work. Between six issues of The Eat. Bang! Kill. Tour and Bingo Love, several characters use mobility equipment such as wheelchairs and crutches. The stories feature people with dwarfism, amputations, vitiligo, and a type of hypertrichosis.

Franklin’s seamless inclusion doesn’t end there, either, as it’s also great to see her include pregnant people as main characters and/or in the background.

In addition to members of the families experiencing various disabilities, Mari in Bingo Love begins to show signs of Alzheimer’s, and it worsens until the end of the main story. Like real life, many other things are going on in the story, so the worsening effects slowly creep up on them. Each family member handles it differently, but most importantly, Hazel and Mari live with it together. After all, they did spend decades forced apart, and Alzheimer’s certainly won’t keep them apart.

Even though Franklin was limited in terms of this representation in the main characters of The Eat. Bang! Kill. Tour, the pages were full of scenes showing people with various disabilities. My favorite character other than the dancer named Peaches (who was adorable) was Vixen’s partner, Elle. I don’t want to spoil much, but the comic would have ended very differently if Elle weren’t in the picture, complimenting Vixen’s stubbornness at times.

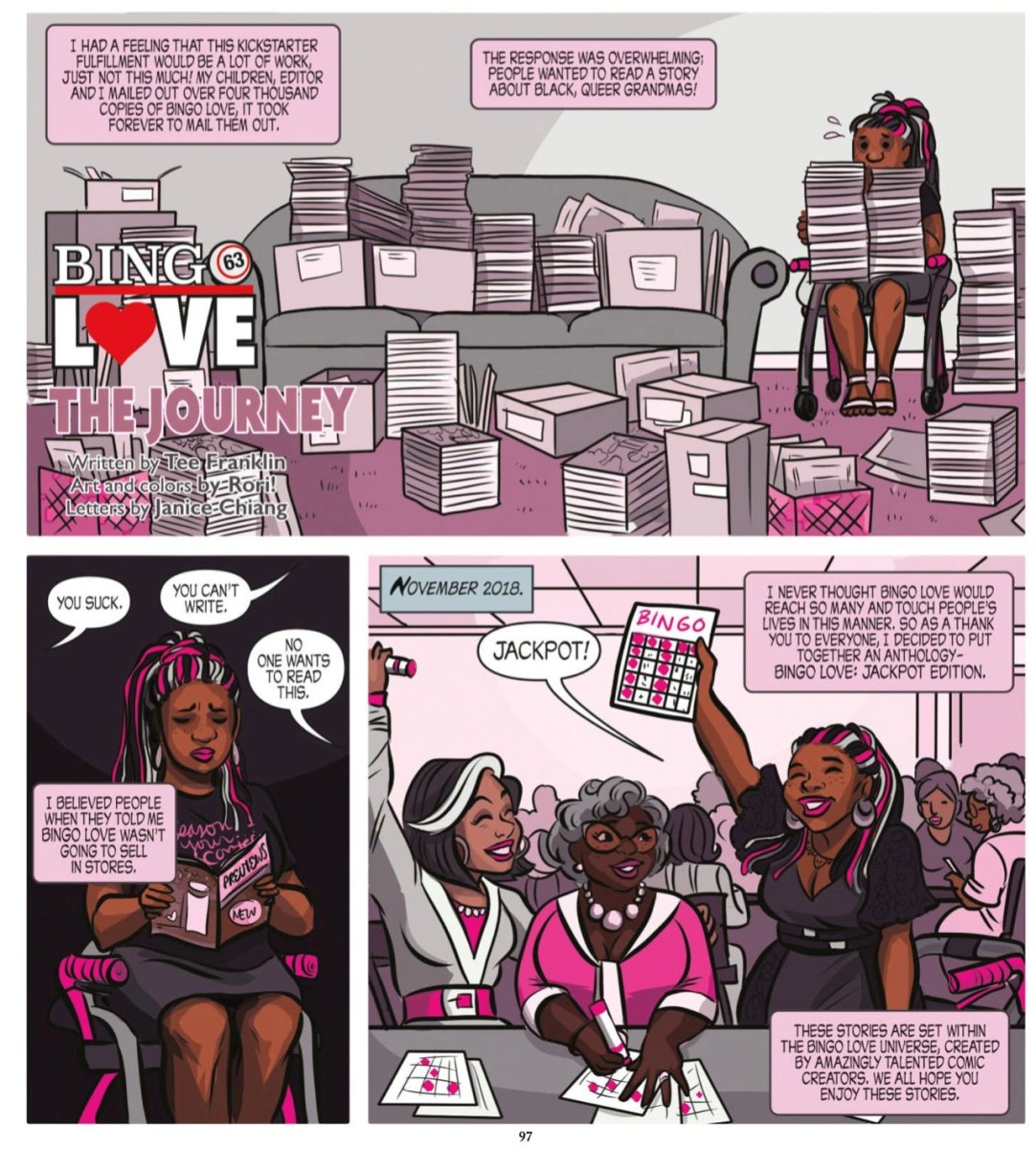

Self-inserts are welcome

In Bingo Love: Jackpot Edition, Franklin explicitly features herself in the comic. She’s in her chair at cons with a big Image Comics banner behind her, worried about how people will receive her book. Franklin is a Black, queer, and disabled woman in a very white and very male field. Despite what the haters online say, self-inserts in comics are nothing new and even extend to adapted stories (like Stephanie Meyer in Twilight or Stan Lee in the MCU or Sony Marvel movies).

However, Franklin’s feel more noteworthy because she’s saying something when she does it (both subtly and overtly). In Bingo Love, Franklin’s facing imposter syndrome as a writer, and in The Eat. Bang! Kill. Tour (both, really), she’s normalizing Black, queer, and disabled bodies and those in sex work. These same markers are still inherently political because society criminalizes and polices each of these to varying degrees, making it even more important to promote that normalization by just letting people be who they are as part of the story.

I love reading Franklin’s stories because they’re heartwarming and laugh-out-loud funny, and she always works with amazing artists who dial up those emotions. I hope that this representation becomes something more common in most comics, be it anti-hero action comics or romance graphic novels.

(Image: Joy San & Jenn St-Onge/Image and Max Sarin/DC Comics.)

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Published: Mar 4, 2022 01:41 pm