‘The Boy and the Heron’ Is a Visual Feast With a Deeply Personal Emotional Core

3.5 parakeet kings out of 5.

In the world of animation, few names are as internationally adored and revered as Hayao Miyazaki. His latest film under Studio Ghibli, The Boy and the Heron, continues the studio’s tradition of whimsical fairytales led by youthful protagonists and full of strange creatures.

But while it may follow a familiar (and successful) formula, The Boy and the Heron’s wandering structure and barrage of characters dilute a potent story, resulting in a visually dazzling film whose emotional core isn’t quite as effectively realized as previous Ghibli flicks.

Starring Soma Santoki and Masaki Suda, The Boy and the Heron is a semi-autobiographical period fantasy that follows Mahito (Santoki), a stony, disciplined young boy living in 1940s Japan. Three years after his mother is killed in a hospital fire in Tokyo, Mahito and his industrialist father Shoichi (Takuya Maki) leave for the rural countryside where Shoichi takes Mahito’s aunt Natsuko (Yoshino Kimora) as his new wife.

Still devastated by his mother’s death and reluctant to embrace his new town and family, Mahito quickly becomes obsessed with capturing a Grey Heron (Suda), a magical creature taunting that beckons him to discover a hidden magical world just beyond the confines of his new home.

Structurally, The Boy and the Heron bears a number of similarities to Alice in Wonderland—though his mother’s death and the family’s relocation serves at the film’s inciting incident, the story itself is much more concerned with exploring the extraordinary people and creatures that populate the strange world within the wall of nearby magical tower built by Mahito’s ancestors. Once down the proverbial rabbit hole, the film and Mahito leap from one unusual fantasy creature to the next, meeting all manner of bloodthirsty talking birds and fire-powered witches, all with the Grey Heron serving as a reluctant guide.

On the one hand, the never-ending barrage of whimsical creatures and surreal monsters Mahito encounters are very much the in-house bread and butter of Studio Ghibli: The precarious but effective combination of unsettling and endearing gives the film a distinct surreal sensibility and makes for a whole slew of dazzling character designs.

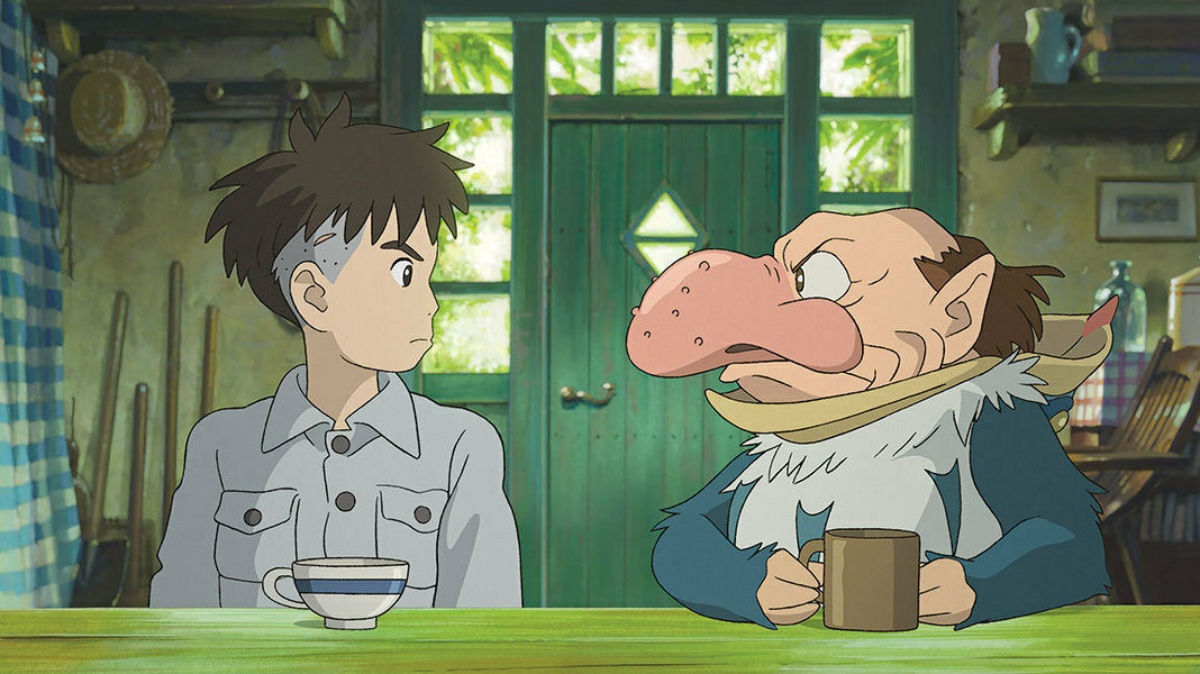

The titular Heron encapsulates Miyazaki’s approach to creating fantasy beasts: Though at first regal and elegant, the Heron slowly begins to grow more unhinged, its gums bulging and its teeth protruding until it’s become a half-man half-bird monstrosity that still somehow manages to charm with a snarky sense of humor and a devil-may-care attitude.

It’s not just the characters who populate the world of the tower, either—the landscape itself is brought to life in breathtaking washes of color and beautiful brushstrokes. The animation shines most in interior scenes, where the meticulously detailed and lush, colorful backdrops sit in stark contrast to the simple lines and cartoonish art style of the characters, making for a plenty of unexpected and striking tableaus.

It’s no mystery why Ghibli has built up a reputation for a house style so beloved and instantly-recognizable that it’s become a stylistic point of inspiration for the entire world of animation. Miyazaki’s understanding of visual storytelling and mastery of the medium is second to none. But while The Boy and the Heron’s fairytale-esque plot structure gives the film ample opportunity to showcase strange characters and beautiful landscapes, the way Mahito seems to simply float from story beat to story beat, dragged along by whichever new resident of the Tower he’s just met, undermines what could’ve been a far more focused, impactful story.

As far as Ghibli protagonists go (or animated fantasy protagonists, for that matter) Mahito is a refreshing subversion of expectations—though he may be young, he’s rigorously disciplined and fiercely defensive. Yes, he may do his fair share of rule-breaking and exploring, but his personality is first and foremost informed by the extreme tragedy he experienced at such a young age. He’s haunted by his mother’s death and unsure of how to cope with the trauma except to put on a brave face and not let anyone in.

He’s a remarkably practical, stony protagonist, but never one who comes off as bratty or unlikable. We know exactly where his standoffishness comes from, and it’s a trait made all the more tragic considering just how painfully young he is. The knowledge that the story is somewhat based on Miyazaki’s own life is another element that lends emotional credence to Mahito’s character. The sequences in which he dreams of his mother surrounded in flame are beautifully animated and utterly heartbreaking.

What’s frustrating, then, is how uninterested The Boy and the Heron seems to be in directly exploring Mahito’s grief and inability to cope with his mother’s death. The film is very clearly structured as an adventure that will give him eventual solace and peace of mind (especially once the nature of the magical tower and its inhabitants, many of whom are blood relatives of Mahito, is revealed), but never slows down enough to truly explore those ideas and bring Mahito and the audience catharsis.

Though the film’s surprising amount of body horror and bloodshed hints at a lingering interest in exploring how death and violence permeate even the most whimsical of fantasy worlds, The Boy and the Heron dances around the themes at its core without ever committing to fully diving into them. Especially with a protagonist as thoughtfully written as Mahito, the choice to tread familiar territory through unlikely creatures and magical encounters rather than face its thematic center head-on makes The Boy and the Heron a visual delight but an ultimately disappointing adventure.

(featured image: Toho)

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]