The Breaking of “Narrative Promises” Through the Lens of Supernatural, Marvel, & More

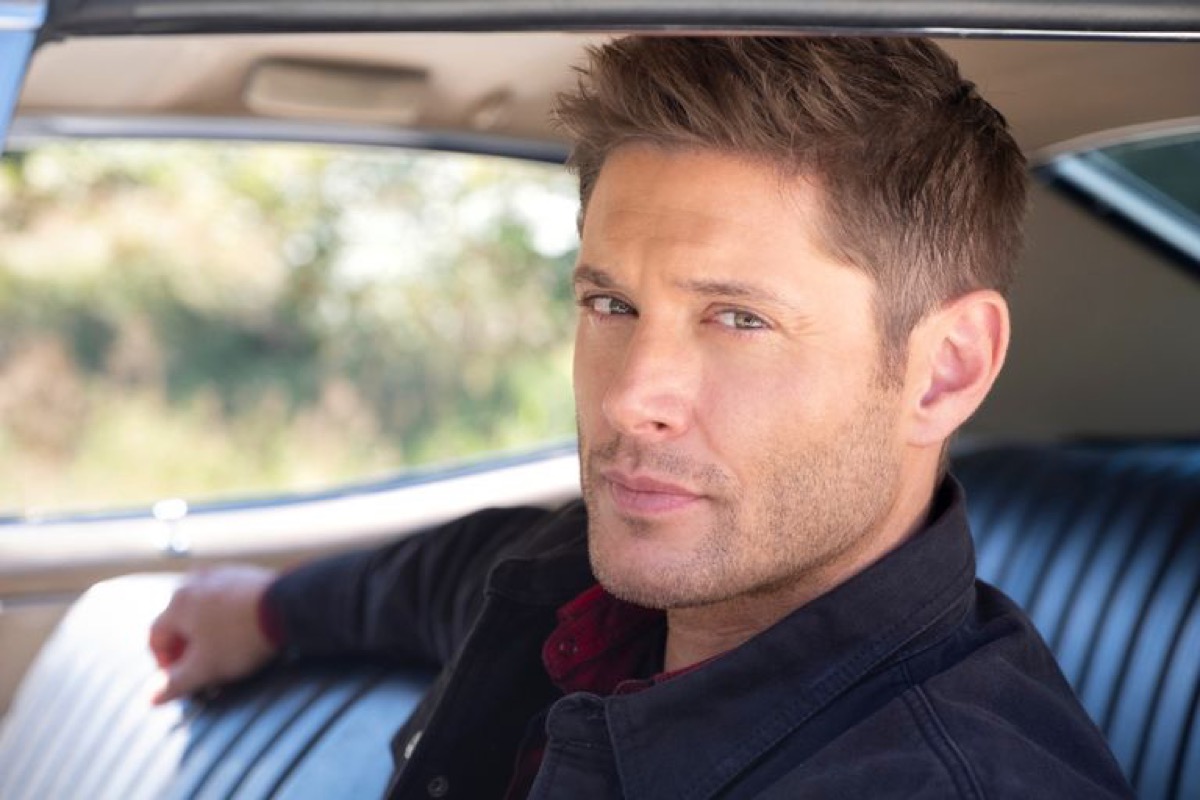

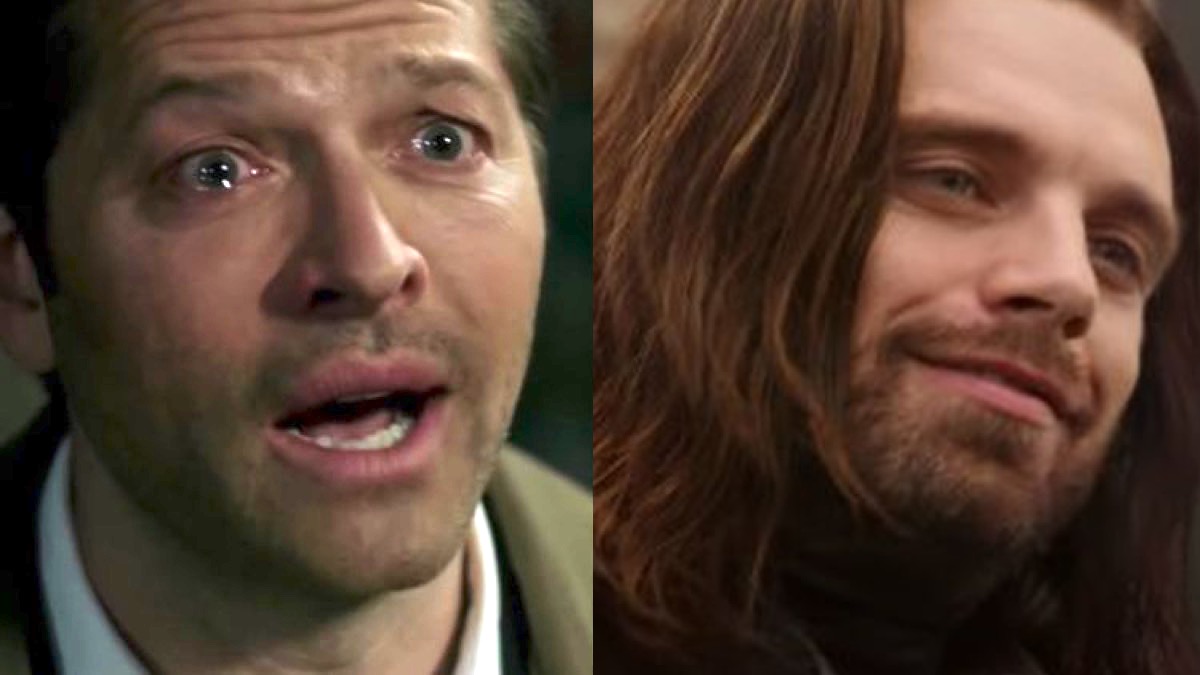

In early November, amidst the pressure of states changing colors and electoral votes being counted, the internet briefly shifted its attention to a, for some, long-awaited episode of television. On fans’ screens, after over a decade of possibility, and many both gentle and harsh denials of the ship’s existence by The Powers That Be, Cas finally confessed his love to Dean on The CW’s Supernatural. In a way, Misha Collins assured fans, it meant he could be counted among the still-painfully-few LGBTQ+ characters that grace popular culture.

With two episodes of the series remaining, fans held their breath to see what might happen next. But in true Supernatural fashion, goldfish-syndrome struck, and once the credits rolled, these powerful words faded from the in-canon memory of both the writing and the characters. Though they had been designed for impact, and impact they had, they did not meaningfully return in the narrative again, save for a few sips of alcohol slugged and a singular mention of Castiel’s name in the finale. In short, “what might happen next” was, as ever, nothing. But this time, at the moment of the series’ end, “nothing” was sealed as the final outcome. Joy turned to outcry.

For some, this outcry was immediately termed “fan-entitlement”—something fans simply believe they have a right to, bound in their own personal interpretations of the show and the “far too great” emboldenment social media has given them to speak their minds. But entitlement has very singular connotations: someone believes they are owed something, and it is grounded in only their beliefs and expectations. In this case, however, and in many others—some that will be touched on in this article—the experience is not nearly as solitary as that. Instead of being this unilateral process of a fan making up their mind that something might happen and then being absurdly angry when denied, the upset actually stems from being promised something by the narrative that never comes to fruition.

A promise is an agreement that takes two.

The fans watching the show and the narrative itself, unfolding before them, come together to make up an understanding of a show, or else, canon becomes wholly incoherent. One can argue that there is no promise in television, that writers can do whatever they’d like, but there are implications of where the story is going buried in the text; there are moments that happen, that fans watch, that should have an impact on the next step in a story. How they have impact may be an unclear prospect with no guarantees, but that they should have impact is a prescription that comes right from the writers’ pens.

The obvious truth, of course, is that when a fan property grows to a certain size, there is simply no pleasing everyone. But this article is not meant as an interrogation of the specificity of what Supernatural should or should not have done in the minutiae of its story, but instead a look at the concept of a larger narrative arc and the idea that there were things throughout the show—and chief of all, this moment of love confession—that were placed in a way that indicated a strong story importance, promising fans something to sink their teeth into, only for the story to never be told at all. Of course, the outcome of a broken promise is hurt.

The best question one can pose is whether—at the moment Castiel told Dean, “I love you,” and proceeded to vanish into the abyss with two whole episodes of remaining time left in the show—anyone truly believed this would never be addressed. Regardless of whether someone is long-time shipper, a casual viewer, or even a person who believes Cas is an interloper on a show that should be purely about two brothers, there is no lack of clarity on the importance a confession of love holds between two characters that have been onscreen together for eleven years—especially not one that also pulls in a larger real-world importance as it starts to nod at the possibility of a representative relationship.

The inclusion of this poignant scene is a narrative promise to fans. It is a promise that says, “Here is a massively important moment that happened at arguably the most massively important narrative time of all. It will have some resolution.” One scene begs another. A can of worms, one the show certainly knows has meaning, has been opened, not by fans, privately in their hearts or “delusionally” in their minds, but onscreen by the show itself. The narrative does not say, “Dean and Cas cannot be in love or even talk about it because the story that has been built cannot allow for it,” but it, in fact, says the exact opposite: Dean and Cas might be in love. At some point, probably, they will talk about it. We simply cannot show it to you even though we took the time to indicate we would.

The finale practically screams for it.

As Dean drives through scene after scene of open stretches of road, in heaven—where Cas is, with full knowledge Cas is alive—fans can practically see Cas showing up as he so often does, in the car next to Dean or behind him in a flutter of wings. And the truth is, while many like to say fans are entitled and can never be pleased, fans—especially queer ones, especially ones who are invested in these beautiful stories that not their delusions but truly canon has built—are very easily pleased because they are starving to be seen by the stories they love. They only, truly, ask not to be disrespected. They only ask for what they are promised by the story: meaning.

One scene of narrative resolution would have turned anguish into understanding or triumph—one concluding moment just to say yes, this happened; yes, this was important; yes, this is what we’ve built, and what we’ve been watching. Here is an ending, long-awaited, whether Dean requited the love or simply told Cas they were only family. One last appearance by Castiel would have given an openly dangling thread of plot the story that was vested in it, and so easily could have been.

But instead, like a slap in the face, and this time a resounding one with the clock run out, what was promised was denied.

And Supernatural is not the only property guilty of this. The narrative promise at the end of, for instance, Marvel’s Captain America: Civil War is that after a dramatic rending of the Avengers, the work of the next movie must necessarily be to begin to bring them back together, but this thread dissipates into the ether in favor of a complete dissolution of the team, ultimately.

The iconic moment when Steve and Tony clash in Siberia is not falling action. It is not the conclusion of a plotline; it is the epicenter of it—the climax, in many ways, a deep wound being dealt that is the set-piece of a whole movie—but there is never any true, deserving catharsis for it. It merely peters out and vanishes instead of ever being meaningfully, emotionally discussed or ever really addressed. In Infinity War, there is almost no acknowledgement of this central story, in favor of meet-cutes between different characters and Thanos’s chase for the stones, and in Endgame, there are brief moments of frustration or apology, but they never come together to form the end of the story. The promise of that iconic clash is never really fulfilled.

In Avengers: Infinity War and Endgame, this happens again on a grand scale. The emotional pièce de résistance of these two movies is when the heroes have to undergo the horror of watching their closest companions vanish into dust. There is a promise in that scene, a bargain that is understood because, otherwise, it carries no emotional weight and doesn’t matter, but its very inclusion implies the writers know that it does. This promise is two-fold:

- Those who are being snapped are meaningful to the ones who they are being snapped in front of, and this pain will be a resonant force in the story to come. The snap itself will be a resonant force.

- These losses will eventually be paid with reunions.

But these promises are kept in inconsistent and largely ineffective ways.

On a macro level, the snap, which was such an intense and harrowing offering at the end of Infinity War, truly goes largely ignored by the story after the final moments of the movie. Setting aside Endgame’s opening sequence, which is as dark as would be expected, the story goes on to don a quasi-comedic tone, more concerned with reliving its greatest hits, adding paint-by-numbers moments that appear to be important but carry no true weight, such as Steve saying “Avengers, Assemble” or holding Thor’s hammer, and making what are clearly hoped to be viral jokes, like “America’s Ass” and Professor Hulk dabbing.

But as both the conclusion of a decade of storytelling, and as the immediate successor to Infinity War’s brutal ending, this story makes no contextual sense. The narrative promised was one of darkness, of pain, of heroes emerging from loss to come together, but both the world at large, which doesn’t seem to have been that affected by the snap that fans can see—and, indeed, Spider-Man: Far From Home actually treats it like a joke—and the heroes, who seem mostly, at worst, kind of sad, seem to have forgotten this promise.

The tone shift from Infinity War to Endgame is so jarring that it is metaphorically neck-breaking. But after asking the audience to invest in the pain and meaning of this loss of humanity, and of these important relationships, it simply falls flat. Instead of continuing the narrative arc set forth, Endgame relies only on moments that never build into really anything. It is an inert final offering that drops the promise of a found family, drops the promise of a desperate battle through true pain, drops the promise of any more evolution or depth for the characters, and overall, for the specific stories living in it, there is no next recourse.

On a micro level, in many ways, there is not a single character Endgame leaves untouched when it comes to the breaking of narrative promises. Thor’s journey to accepting his place as king is erased, as is the growth he achieves with his brother. Nat’s importance to the family she has built for herself is erased. Bruce is … simply erased. Clint is annihilated as a character completely, and though maybe Tony gets the child the story has been hinting at for so long, Morgan Stark is barely a blip of screen time.

But, tying it back to the earlier discussion of the promises built by the snap in Infinity War, one of the most painful narrative promises that is yanked back, for some fans, is the one the audience is offered in their first realizations something has gone wrong when, of all the characters, Bucky Barnes is the first to vanish into dust in front of Steve Rogers.

It is interesting that though the writers and narrative knew enough to know that this would be an incredible emotional gut punch to audiences, starting the sequence of disappearances off with Bucky once again slipping out of Steve’s grip, this “inseparable, on both schoolyard and battlefield” relationship is both emotionally and literally not granted the promise of this disappearance. Once the narratively-quantified emotional weight of Bucky’s meaning to Steve is used to underscore the pain of the snap, Bucky’s importance is entirely excised from the narrative—though, much like in the case of Dean and Cas, the narrative both asks for it and offers opportunity for it.

The most glaring of these moments comes in the early scenes of Endgame, when Steve is sitting in therapy listening to a man describe the pain of losing his partner to the snap and, in response, Steve is not allowed to use the scene to acknowledge his own pain from the events of Infinity War, but rather—quite disingenuously, given the circumstances, and more than a little clumsily, as far as fluid narrative goes—discusses losing Peggy. Whether one sees the relationship between Bucky and Steve as romantic or simply intimate, he is the clear choice for Steve’s therapy discussion, as the resonant figure the story has told viewers Steve, specifically, lost to the snap.

In terms of where the story has taken its viewers, Steve lost Bucky to the snap five years prior and is in a discussion group for snap survivors. It is the highlighted thought and the purpose to have the discussion at all. Peggy, meanwhile, who Steve has yet no knowledge of being in the future of his narrative, was lost to natural causes almost a decade before that therapy scene. This moment was kissed with Bucky’s name and would also have been an appropriate place to discuss Steve’s other losses, Sam or Wanda, but the narrative suddenly, sharply implies whatever story the audience had been watching in prior movies about Steve and his future family is gone.

This feeling is underscored again when Steve looks at the compass with Peggy’s image before going to face Thanos. Narratively, she has nothing to do with Thanos. Narratively, this would be a great moment to think about the people Steve lost because of the Titan as motivation for embarking upon his defeat.

And in fact, though Tony, for instance, thinks about Peter from time to time and even tells Steve, “I lost the kid,” Bucky’s name is never mentioned in grief by Steve. The brief emotionality Steve faces is attributed to anything but this. It is carefully given to the overall state of the world, vaguely, to losing Peggy, from out of the blue, but never to watching Bucky fade from his life again, for a traumatic fourth time, the way the death scene in Infinity War whispered that it would. There is never an exploration of that pain while Bucky is gone, and glaringly, a mirror to the loss, a reunion, on the battlefield or off, is never given to the fans that felt most intensely what the story asked of them to feel.

And of course, literally and more harrowingly, the whole promise of Steve’s arc across his many movies is undone by Endgame, as Steve’s project of growth, evolution, and settling into a new life and home in the future is suddenly and determinedly wiped clean to fulfill an arc that gathered dust for a decade.

Did the narrative promise that Steve and Peggy might share a dance? Sure, it did—just like Supernatural promised, at one point, that the show was just about two brothers, and Game of Thrones, which this article does not have space to fully discuss, promised Jaime Lannister would always choose Cersei. While these markers did exist, at points, more narrative real estate was ultimately spent without them, and in many ways, belaying them, than was spent on the thin, however catchy, phrases of plot. The story simply grew beyond them. Acknowledging them over the actual narrative fans invested in is truly disrespectful.

This is time that was allotted to these storylines by canon, offering an expectation of meaning and importance, offering what results in a promise—not time the fans imagined or made up, not something they feel nebulously entitled to, but time they spent on plots the canon gave to them. (Cas means something to Dean after all these years and a love confession. Bucky means something to Steve after all these years and a snap. Jaime’s project of growth and his meaningful relationship with Brienne is something worth investing in.)

But instead of saying, yes, you spent all this time watching these scenes, feeling these moments, taking this in—you grew with this character, with these relationships (grew in many cases away from the set starting point)—here is your promised meaning, again and again, these properties snatch the rug away and then pretend blithely they cannot understand why “entitled fans” are so upset.

And just to be clear, this is not “just about the ship,” it is about the story. In many cases, the ship and the story are, indeed, inextricably linked, because the story is the basis of the ship. But I promise that not a singular person truly believed that Marvel would make Stucky a romantic relationship in Endgame—not one. But what they did believe was that there would be even a breath given to the meaning of this relationship, after it was at the center of Steve Rogers’ arc for so long—a belief that was promised to them by everything in nearly every part of Steve’s story, by Steve watching Bucky disappear into a puff of dust, up until the last.

But instead of a promised reunion, there was a loss, and then a loss, and nothing—the narrative, the relationship, the friendship, sacrificed on the altar. And, if in the cases of Dean & Cas and Jaime & Brienne, if the fans did truly believe the ship could happen, it is because the story led them there. While it is not “just about the ship,” it does not feel coincidental that the reneging of narrative promises happens to characters and relationships that orbit queer ships so often. In fact, it feels purposeful.

At the end of the day, it takes two to tango, and though it’s true that properties can do whatever they want, it doesn’t mean they should. There’s a reason why shows like Avatar: The Last Airbender and Hannibal are so universally loved by their fans, and that is because they tell the stories they promise to tell and unfold satisfying arcs and resolutions—and not out of the desire for shock value, nor for spite, nor fear, do they stray from them.

Simply, they give to fans the one thing that is owed to them: respect.

(featured image: The CW/Marvel Entertainment)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]